![]()

High Gothic Splendor

The Duomo

Like Siena itself, the Duomo is a magnificent example of what can result from the chaotic concatenation of uncontrolled forces and events. In 1258 the work on a new cathedral was entrusted to the monks of San Galgano, with a reputation for efficiency and competance, but by 1297 the architect responsible for the façade had left the project, angered by arguments with the commune over finance and control.

Then in 1317 a group of prominent citizens decided that the cathedral was too small and by 1339 orders were given for a church that would have been the second largest in Europe after St. Peter’s in Rome. Successive extensions were started and then abandoned when cracks appeared, and the whole grandiose project ground to a halt with the black death in 1348.

Nevertheless, what remains is a breathtaking structure of unique magnificence. Its striking bands of black and white marble were patterned after examples in Pisa and Lucca. The Rough Guide observes laconically that one's experience of the interior “is compromised by the vast summer crowds streaming through its turnstiles”; but at the end of February the entrance with its labyrinth of barriers was so deserted that we wondered if it were open. Inside, the few tours being taken around were lost in the architectural immensity.

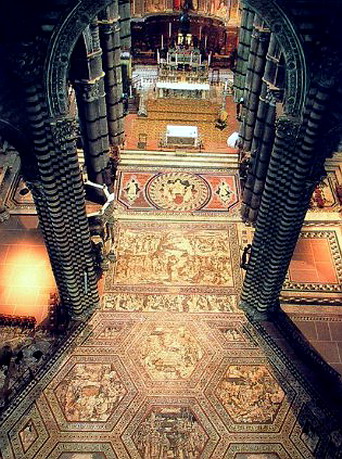

The cathedral's literal and metaphorical foundation is a floor consisting of fifty-two panels of inlaid, etched and colored marble. Much of it is covered through most of the year to protect it from the tramping hoards—otherwise it would long ago have blown away as dust. During the summer when it is most revealed it is also most hidden by the crowds, and so the best readily available overall view is in photographs. The floor's history is concisely outlined in Wikepedia.

The cathedral's literal and metaphorical foundation is a floor consisting of fifty-two panels of inlaid, etched and colored marble. Much of it is covered through most of the year to protect it from the tramping hoards—otherwise it would long ago have blown away as dust. During the summer when it is most revealed it is also most hidden by the crowds, and so the best readily available overall view is in photographs. The floor's history is concisely outlined in Wikepedia.  Of the many themes so tantalizingly touched on, my favorite is the fickle goddess Fortuna, whose image heads a previous page. With her feet resting unstably on a globe and a ship and a strong wind filling her sail, she is a fitting embodiment of the utter insecurity of life in plague-ridden mediaeval Europe (or our modern runaway planet, for that matter). Her quixotic wheel is pictured in another part of the floor, unhappy mortals clinging in desperation as it inexorably revolves.

Of the many themes so tantalizingly touched on, my favorite is the fickle goddess Fortuna, whose image heads a previous page. With her feet resting unstably on a globe and a ship and a strong wind filling her sail, she is a fitting embodiment of the utter insecurity of life in plague-ridden mediaeval Europe (or our modern runaway planet, for that matter). Her quixotic wheel is pictured in another part of the floor, unhappy mortals clinging in desperation as it inexorably revolves.

Set back from the left aisle, the Libraria Piccolomini almost succeeds in upstaging the duomo’s magnificent nave. In brilliantly colorful murals it commemorates Pope Pius II, the archetypal Renaissance intellectual whom Jakob Burkhardt made the virtual hero of his Civilization of the Renaissance in Italy. If only he had contented himself with poetry, geography and his wise Commentaries! He ended his eight-year papacy with a disasterous crusade to retake Constantinople from the Turks. Today, he is remembered chiefly for having inspired some rather splendid interior decoration.

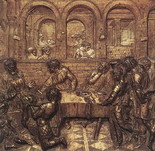

Thanks to the cathedral’s steep hillside location, the baptistry was given its own separate magnificence tucked away under the choir. Framed by the vaulted jewel -like frescoes, the font is an early 15th century masterpiece to which all the major sculptors of the time contributed. Around its base is a sequence of bas-reliefs narrating the life of John the Baptist, yet another preacher who lost his head over a pretty girl. Donatello captures the scene with a vividness that dropped me straight into the recent Covent Garden performance of Richard Strauss’ Salome, a work of magnificent decadence that makes punk rock sound like nursery rhymes.

-like frescoes, the font is an early 15th century masterpiece to which all the major sculptors of the time contributed. Around its base is a sequence of bas-reliefs narrating the life of John the Baptist, yet another preacher who lost his head over a pretty girl. Donatello captures the scene with a vividness that dropped me straight into the recent Covent Garden performance of Richard Strauss’ Salome, a work of magnificent decadence that makes punk rock sound like nursery rhymes.

In the Duomo’s museum next door are the statues by Giovani Pisano that have been removed from the Duomo’s façade. Philosophers and prophets tower severely overhead, admonishing the tourists to mend their ways.

Fleeing the wrath to come, they encounter a delicate gold leaf rose and a baroquely housed momento mori.

©2008 John Whiting