![]()

BERLIN REVISITED

1998

Tuesday, February 17

I'm returning to Berlin with a certain degree of trepidation. Beginning in 1983, when The Wall was an object of terror rather than nostalgia, my first visits were to the Eastern zone. When I finally entered the West some ten years later, I feared that my cover might be blown and I would be whisked back through Checkpoint Charlie.

This time the threat is biological as well as psychological. I've been saying for years that, once I had worked with the Berlin Philharmonic, I could die happy. Now that the moment is imminent, I begin to wonder if Fate holds us responsible for our idle, extravagant remarks. As my father used to delight in misquoting (thus demonstrating the importance of both scansion and punctuation), “There is a destiny that shapes our ends rough, hue them how we will.”

But it would almost be worth it, even if my bargain were divinely enforced. Four concerts with the Berlin Phil in their hall of residence, the Philharmonie, under Simon Rattle! What a denoument it would be to slump forward over the mixer as the last gentle chord of the Berio Sinfonia died away, the tenor E modulating mournfully down to an E-flat.

Four concerts with the same content, in a hall seating 2300 people? That's 9200 warm bodies for a program which starts with what is still, for the usual symphony audience, uncompromisingly avant-garde music. True, the second half is Mahler's much-loved second symphony, and it's been placed after the interval so the Mahler fans can't cop out; nevertheless, in London an orchestra would be lucky to respectably fill the Royal Festival Hall for a single Berio performance.

This isn’t one of those occasions when I get to drive across Europe, using a distant concert as an excuse for filling my cellar with wine, my cupboard with menus, and the back of my van with stickers. The Philharmonie has a sound system already installed and, being German, it’s likely to be a good one. I’ve already had a fax with a floor plan of the hall, indicating the location of the loudspeakers. The space unfolds like a flower, with planes of seats like petals slanting outwards in all directions from the stage and a rising bank at the rear which could accommodate a Morman-Tabernacle-sized chorus for Mahler’s Symphony of a Thousand. I’ve been told that it is one of the few modern concert halls with really splendid acoustics. I’ll believe it when I hear it.

This isn’t one of those occasions when I get to drive across Europe, using a distant concert as an excuse for filling my cellar with wine, my cupboard with menus, and the back of my van with stickers. The Philharmonie has a sound system already installed and, being German, it’s likely to be a good one. I’ve already had a fax with a floor plan of the hall, indicating the location of the loudspeakers. The space unfolds like a flower, with planes of seats like petals slanting outwards in all directions from the stage and a rising bank at the rear which could accommodate a Morman-Tabernacle-sized chorus for Mahler’s Symphony of a Thousand. I’ve been told that it is one of the few modern concert halls with really splendid acoustics. I’ll believe it when I hear it.

Since I have to make technical arrangements at the hall in advance of the one-and-only full rehearsal, I must fly to Berlin the night before the singers. Ticket arrangements have been made for us by the orchestra, unfortunately on Brutish Airways (that was a deliciously genuine typo which I must leave on the page). Time abroad is so precious that I like it to begin as soon as I set foot on the plane; this time I’m on British soil, as it were, until I alight. In the meantime, we’re treated to a cold chicken salad which, if we were not arriving so late, I would pass up in favor of a Berlin anything, even a jelly doughnut (ein Berliner), which JFK once so proudly proclaimed himself to be.

I’ll have to take a cab to the hotel from the airport, but I’ll get deutschmarks when I arrive. Such is my fond hope. The gateway to Germany’s old/new capital proves to be somewhere on a par with the access to some midwestern hick town: grim, primitive, not a single shop, bank or cash point open at 11 pm. There are only a couple of taxis outside, and neither of them takes credit cards. I’m at the mercy of a good-natured Polish driver who’s prepared to accept pounds sterling. Something tells me that the change I’ll get from a twenty pound note won’t buy me enough mustard to season an Eisbein. I’m correct. The ride costs me three-fold.

THE HOTEL BERLIN is one of those great anonymous structures that might have started life as a government office building. My room has a four-digit number which, it turns out, identifies the wing of the building, then the floor, then the room itself. Nothing in the lift indicates this vital fact, so I go up and down a couple of times, seeking in vain for my destination, until a sympathetic guest explains the system to me and points me in the right direction. The room is big, the bed is comfortable, the windows actually open, and the TV doesn’t trick the unwary into watching the pay movies. The only ominous sign as I go to sleep is a gentle burp with the persistent odor of chicken salad . . .

THE HOTEL BERLIN is one of those great anonymous structures that might have started life as a government office building. My room has a four-digit number which, it turns out, identifies the wing of the building, then the floor, then the room itself. Nothing in the lift indicates this vital fact, so I go up and down a couple of times, seeking in vain for my destination, until a sympathetic guest explains the system to me and points me in the right direction. The room is big, the bed is comfortable, the windows actually open, and the TV doesn’t trick the unwary into watching the pay movies. The only ominous sign as I go to sleep is a gentle burp with the persistent odor of chicken salad . . .

Wednesday February 18

Here in Berlin life starts early. I've been asked to show up at the Philharmonie at 8am to get the sound system sorted out. Fortunately, the Hotel Berlin is used to such early-bird schedules; breakfast begins at 6:30. It's a typically Germanic spread, though not on the obscene scale that Mary and I experienced a decade ago at Berlin's Hotel Inter-Continental. There the eggs, sausages, prawns, herrings, cheeses and pastries continued to pile up on the buffet tables (next to the champagne) until closing time at 11am. “What happens to all this food?” Mary asked a waitress. “It is thrown away,” she replied. “Every bit. You would cry to see it.” Even more senseless than conspicuous consumption is conspicuous destruction. Under modern capitalism, Franz Boas need not have joined the Kwakiutls to discover the potlatch.

I reckon that I can walk from the hotel to the Philharmonie in about half an hour: from Lützow Platz along the Landwehr Kanal (just where did Rosa Luxembourg's body float to the surface?) and then north on Potzdamer Strasse. It's a bleak walk—nobody is on the streets at this hour. I only meet one other Fussgänger.

When I arrive at Potzdamer Platz at the corner of what was once The Wall, it proves to be a massive building site: what was open desolation is rapidly being turned into enclosed desolation. I'm surrounded with the skeletons of what will soon be the serried ranks of skyscrapers bearing the logos of every major supra-national corporation. From the close proximity of the foundations, it is obvious that any blades of grass appearing between them will be unplanned and unwelcome. Why is it that the 19th century robber barons allowed so much open space for trees and flowers? Perhaps they were not yet totally ruled by their accountants.

WHEN the Philharmonie was built in the early 1960s, its design was unique. The architect, H Scharoun, had come to the city as a young man in 1912 and was well-established on the Berlin scene; this probably helped him to gain acceptance for his revolutionary ideas. Unlike most modern concert halls, it actually worked, so when a smaller chamber music hall was built next door twenty years later, he was allowed to follow the same pattern on a smaller scale. Thus the old German proverb was disproved: When theory and practice coincide, they are probably both wrong.

WHEN the Philharmonie was built in the early 1960s, its design was unique. The architect, H Scharoun, had come to the city as a young man in 1912 and was well-established on the Berlin scene; this probably helped him to gain acceptance for his revolutionary ideas. Unlike most modern concert halls, it actually worked, so when a smaller chamber music hall was built next door twenty years later, he was allowed to follow the same pattern on a smaller scale. Thus the old German proverb was disproved: When theory and practice coincide, they are probably both wrong.

When I arrive at just after 8, the stage has already been set up and the mixer installed at an ideal spot about half-way back in the hall. The two technicians in charge couldn't possibly be more helpful—or sensible. When the singers' eight microphones that I've brought with me are installed and tested, it is immediately obvious that the sound system has been well thought out and assembled from first class components. What about the requirements of German radio/television, who will be broadcasting an edited compilation of the concerts? They are quite prepared to take a feed from my mix of the voices and add it to their own orchestral mix. In Germany this is totally outside my experience: their usual practice is to take a separate feed of each vocal microphone and create their own mix, even though the Tonmeister may be totally unfamiliar with the work. Within an hour of my arrival we're through and I'm free until the rehearsal at 4:15.

DURING the morning I've gradually become aware that Brutish Airways has given me an unwelcome momento of last night's flight. I'm feeling decidedly off-color: a sure indication is my total lack of interest in the approaching lunch-time. Meanwhile, my hosts have offered to show me the sanctum sanctorum, the control room in which so many Deutsche Grammophon recordings were mixed for Herbert von Karajan. I can't refuse and so, screwing my courage to the sticking point, I set out with them through the backstage labyrinth.

We arrive at a large room dominated by an enormous mixing desk which could have been the centerpiece of a James Bond movie. The one surprising feature is a pair of English B&W loudspeakers. What are they doing here? My host explains that they have become so much the recording industry norm that producers expect to find them wherever they go—even Karajan preferred them. “What do you think?” I ask. He shrugs his shoulders. He is not surprised when I tell him that the manufacturers gave away many expensive pairs on permanent loan to those who were prepared to list them among their recording credits. Selling soap, soup or sound involves the same devious practices.

AT LAST I'm out in the open air again. Here at the Potzdamer Platz I'm too close to Unter den Linden not to walk up Friedrichstrasse along the site of The Wall—I can't help capitalizing it! A preserved little hunk sits on my study windowsill; as many segments miraculously survive as pieces of the true cross. A few hundred yards have been left in place, its fading murals dedicated optimistically to peace and freedom.

After many years of working and travelling in Germany, I remain equivocal. What country has within living memory committed such atrocities? On the other hand, what other nation in history has erected monuments to remind its citizens in perpituity of their collective crimes? It's not just that the Allies were there to rub their noses in it. America has taken well over a century to sentimentalize its despised and slaughtered Redskins, and as for Israel's exiled Palestinians. . .

Aside from the contents of its shops, Unter den Linden has changed surprisingly little. I step inside the eponymous hotel where Electric Phoenix once spent a large wad of its unexportable East German marks on a surprisingly good dinner. The long hall is still filled with wicke r furniture and the decor of the restaurant, with its clusters of beige plastic bubbles suspended from the ceiling, is totally unaltered. I can even identify the table where we sat. Outside is a banner offering bed and breakfast for 99 deutschmarks. That's around £35. Thirty-five pounds! In the middle of London that might get you an overnight parking place.

r furniture and the decor of the restaurant, with its clusters of beige plastic bubbles suspended from the ceiling, is totally unaltered. I can even identify the table where we sat. Outside is a banner offering bed and breakfast for 99 deutschmarks. That's around £35. Thirty-five pounds! In the middle of London that might get you an overnight parking place.

Across the street is a shop where Daryl Runswick bought the complete orchestral scores of the Mozart piano concerti for the price of a good pair of concert tickets in London. (Much less than similar seats at Covent Garden!) Today it's selling tawdry prints and cheap souvenirs. The leftover scores were probably torn apart to line the threadbare garments of the homeless shivering under the Friedrichsbrücke.

I want to walk all the way to Alexanderplatz, but the chicken salad is getting the better of me. Contrary to my time-honored principles, I hail a cab and head back to the hotel. Just two-and-half hours of rehearsal to get through and I can go to bed.

I needn't have worried. When the body has done something a hundred times, it knows what to do without instruction. The Berlin Phil, on three rehearsals, is playing better than most orchestras on opening night. The singers balance themselves. The sound system and the hall are crystal clear. I could push up the faders and go to sleep.

By 8 o'clock I'm in the hotel restaurant, desultorily putting away the blandest pasta dish on the menu. Then to bed, where a fitful sleep is punctuated with a serial dream in which the supra-national food companies develop a highly addictive substance which makes everything taste wonderful, distribute it free for six months, and then market it as an expensive luxury item like truffles and caviar. I never discover the ingredients.

Thursday February 19

I’m grateful that I’ve never been an actor in a successful long-running play. If the inquisitors in Nineteen Eighty-Four’s Room 101 were to seek out my personal hell, they would soon discover that it was bounding on stage and chirping “Tennis anyone?” for all eternity. However, the closest I’ve come—mixing and balancing the eight voices against the orchestra in Luciano Berio’s Sinfonia—is a task I always look forward to, and not merely because it takes me to exciting cities with great restaurants. It is a recurrent and unrelenting challenge. At one extreme, I am forced to salvage some coherence out of sloppy, incoherent orchestral playing and echoing acoustics. At the other, when the orchestra is playing with easy precision and the hall is a gently springy cushion from which the sounds bounce quickly and lightly back, I am free to search out the voices that are most interesting at the moment, or to point up the constantly evolving dialog between vocal and instrumental lines.

The third movement is the most difficult, not only because of the complexity and density of its structure, but because it makes demands which, in the concert hall, are mutually contradictory. Over the musical framework, which is the scherzo from Mahler’s 2nd symphony, with familiar fragments from other works suddenly surfacing like flotsam from the wreckage of musical history, the narrative voice of an old-fashioned American radio announcer, casual and intimate, provides a running commentary (from Samuel Beckett’s The Unnameable) which often relates to these interjections, remaining largely intelligible against the massed forces of the out-sized orchestra. There are clues that the voice should not always dominate: sometimes you can barely hear it, the narrator says and an alto once screams, Say it again louder! But audiences are conditioned by film and television. If they observe their cicerone’s lips moving and don’t hear reassuring noises they feel abandoned, and so I am sometimes morally pressured into slightly raising the narrative level, particularly when near-by members of the audience turn and look accusingly in my direction.

The problem virtually disappears in a recording which is designed to be listened to at home. These elements can then occupy different acoustic space, just as they occupy different psychological space. The acoustic space around the narrator can be more dry and intimate, as it would naturally be in a domestic environment, while the orchestra can be contained within its own reverberant space, because we are accustomed to it: no one protests that a two-second decay in the living room is “unrealistic”.

But a concert hall emphasizes and even exaggerates the problem, particularly if it has the sort of long rich resonance which favors romantic symphonies and makes bad orchestras sound better. This is the sworn enemy of intelligibility; such a conflict is the principle cause of the failure of multi-purpose auditoria. Raising voice levels doesn’t help; it only makes matters worse by multiplying the reflections. One can only roll off the bass frequencies which cause the worst problems, boost the upper-mids where most speech articulation is centered, and hope for the best.

All that, however, is a zillion miles away from the Philharmonie. The morning rehearsal is a single run-through, with no problems to be worked out. Simon has chosen to spend most of his time on the Mahler 2nd because, as he slyly remarks, “They’re used to doing it differently.”

STILL A BIT fragile after the Chicken Salad Encounter, I go back to my hotel room between the morning rehearsal and the evening performance. But KDW, the Harrod’s of Berlin, beckons from just a couple of blocks away. The Feinschmäcker Etage on the top floor is a glutton’s wet dream: a spider’s web of endless aisles leading through the devil’s own display of irresistible temptations, luscious gleanings from the world’s cuisines. (They should play the third movement of Sinfonia softly in the background.)

STILL A BIT fragile after the Chicken Salad Encounter, I go back to my hotel room between the morning rehearsal and the evening performance. But KDW, the Harrod’s of Berlin, beckons from just a couple of blocks away. The Feinschmäcker Etage on the top floor is a glutton’s wet dream: a spider’s web of endless aisles leading through the devil’s own display of irresistible temptations, luscious gleanings from the world’s cuisines. (They should play the third movement of Sinfonia softly in the background.)

Today I survey it all with lofty objectivity. My still quietly churning tubes, rather than allowing me to zero in on the nearest goodies, compel me to observe the larger scene. I notice for the first time (or have the displays changed so much in half-a-dozen years?) that, for every counter of cheese, fish, meat, or freshly prepared food, there seem to be miles of shelves bearing canned and packaged American clichés: Ritz crackers, Heinz soups, Kellogg’s breakfast cereals. The buyers appear to have targeted the tourist more than the serious foodie, with frequent counters where you are encouraged to sit and nosh. There’s even a Paul Bocuse counter, where young men turn out factory replicas of haute cuisine masterpieces. I satisfy my modest hunger with a small dish of blackcurrant sorbet and come away with no more than a proprietary shopping bag, just to show I’ve been there.

THIS EVENING, after the first performance, I’m ecstatically happy. The right conductor, the right orchestra, the right singers (as always with Electric Phoenix), the right hall—and even the right audience, sufficiently familiar with the standard repertoire to recognize Berio’s constant allusions, but open-minded enough to absorb the alchemical changes to which he subjects them. Three more performances in three days: can they get even better?

After tonight’s success I’m once more actively hungry and ready for the Berlin Experience. The first night’s meal must be an Eisbein at Hardtke. I even feel up to walking there: first, a few minutes’ stroll northwest along the Kurfursten-Strasse to the blackened ruins of the Kaiser Wilhelm Memorial. Built at the turn of the century, this bloated Romanesque excrescence was mercifully bombed down to a stunted tower during WWII and allowed to stand as a monument both to the destructiveness of war and the futility of grandiose architectural excess. It is surrounded with gaudy shrines to unbridled commerce which, alas, no further wars are likely to ameliorate.

After tonight’s success I’m once more actively hungry and ready for the Berlin Experience. The first night’s meal must be an Eisbein at Hardtke. I even feel up to walking there: first, a few minutes’ stroll northwest along the Kurfursten-Strasse to the blackened ruins of the Kaiser Wilhelm Memorial. Built at the turn of the century, this bloated Romanesque excrescence was mercifully bombed down to a stunted tower during WWII and allowed to stand as a monument both to the destructiveness of war and the futility of grandiose architectural excess. It is surrounded with gaudy shrines to unbridled commerce which, alas, no further wars are likely to ameliorate.

Hardtke is still there down a side street just off the Kurdam, its smoke-browned walls and ceiling redolent of a thousand fat cigars. My huge pig’s knuckle arrives with its obligatory sauerkraut and mashed potato. Have I become blasé? Everything seems tasteless and watery. I desultorily put away enough to stave off hunger and turn my attention to the clientele: stout middle-aged women in sturdy flat shoes and alpine hats, accompanied by their even more substantial male appendages, both looming like extra-terrestrial vegitation in their loden-coat green. They shovel away the vast portions of food until their plates are as bare their city's newly-leveled building sites.

Friday February 20

Along with uncountable channels in German and French, plus pay movies of various degrees of pornography, Hotel Berlin’s television service offers BBC World. This quaint channel looks and sounds like the BBC at home in the prehistoric days before John Birt. Instead of screaming kids of all ages jumping about and yelling for your attention, civilized men and women sit in front of the camera and tell you in lucid prose what you’re about to watch. It also has an unfortunate habit of telling the truth, which made it necessary for Murdock to dump it from his China Sky service after the slight unpleasantness in Tiananmen Square.

This morning I switched it on and saw the last half hour of a two-year-old interview with the late Martha Gelhorn. This remarkable woman in her eighties succeeded until the end in being simultaneously intelligent, succinct, furious at injustice, and sexy as hell. Rather than make a career of having been married to Ernest Hemingway, she restlessly pursued the world’s accidents that were going someplace to happen. She reported, not what she was told, but what she saw. She even kept a proper perspective on Papa, remembering him fairly as both a figment of his own imagination and a highly disciplined inventor of modern English prose. Has her kind been adequately replaced by the fly-blown crotch-rags that fill our screens? Whatever turns ya on. . .

TODAY IS all mine until this evening’s concert. First on the list is to take the U-bahn number 2 (the one that used to stop at Friedrichstrasse and turn everyone out for a passport check and the compulsory purchase of East German marks) all the way to Alexanderplatz. For one accustomed to the rigidly enforced barrier controls of London transport, which have come to resemble those of the old East Berlin frontier, travel today on Berlin’s rail and bus system is agreeably laid back. The machines tell you in German and in English what sort of ticket you should buy and what it costs; from there it’s up to you. You buy your ticket, stick it in a machine to validate it, and then travel at will. If you’re caught cadging a freebie, you’re fined on the spot, but that seems to happen infrequently. In Frankfurt, where I worked for three months and took the S-Bahn every day, I was never challenged. This morning in Berlin even the hippies are buying tickets. They also wait for pedestrian lights to turn green. Some call it brain-washing; others call it citizenship.

TODAY IS all mine until this evening’s concert. First on the list is to take the U-bahn number 2 (the one that used to stop at Friedrichstrasse and turn everyone out for a passport check and the compulsory purchase of East German marks) all the way to Alexanderplatz. For one accustomed to the rigidly enforced barrier controls of London transport, which have come to resemble those of the old East Berlin frontier, travel today on Berlin’s rail and bus system is agreeably laid back. The machines tell you in German and in English what sort of ticket you should buy and what it costs; from there it’s up to you. You buy your ticket, stick it in a machine to validate it, and then travel at will. If you’re caught cadging a freebie, you’re fined on the spot, but that seems to happen infrequently. In Frankfurt, where I worked for three months and took the S-Bahn every day, I was never challenged. This morning in Berlin even the hippies are buying tickets. They also wait for pedestrian lights to turn green. Some call it brain-washing; others call it citizenship.

For a frequent captive of London’s Northern Line, the ride to Alexanderplatz is a holiday in itself. The cars are new, clean and uncrowded, the tracks are smooth, the noise level is low. Graffiti artists, apparently frustrated by the speed with which their work is expunged, leave their mementos scratched deeply into the window glass. With the morning sun behind them, they provide a shimmering iridescence to the spotless interiors.

Alexanderplatz is architecturally much the same as I remember, but the old state superstore with its miles of empty shelves is now a sleekly facaded branch of Kaufhof, a sort of German Sears Roebuck. When Mary and I were there a decade ago we watched people standing in three separate lines to buy a single item: first a line to get a basket, then a line to procure a sales ticket, then a line to pay for it. Without too much effort, we resisted the urge to buy matching his/hers blue pinstripe double-breasted suits. Now the East Berliners can buy everything they want without having to wait for anything—except the money.

Back outside, although the architecture is not particularly worse than that which surrounds the Breitscheidplatz at the elbow of the Ku-damm, the effect is drab and depressing. I remembered an experience years ago in Leningrad. Fellow-travelers (mine, not Marx’s) complained that the soft pastel buildings were dull and uninteresting. I couldn’t understand what they were talking about; I thought that the miles of gentle colors and classic architecture were beautiful. And then I realized that what was missing was the loud confusion of billboards, neon signs and sprayed graffiti. Whereupon a flash of enlightenment came to me, as to Saul on the road to Damascus: billboards and graffiti are opposite sides of the same coin, which represents the ego’s massive defacing of the landscape. The obverse or socially licensed side is rewarded with enormous salaries, the reverse or illicit side is punished by fine or imprisonment.

The weather is sunny, almost warm. In one corner of the square a boy perhaps still in his teens unpacks a rickety xylophone without resonators and a cheap portable hi-fi. A music-minus-one accompaniment begins to distort the tiny loudspeakers and the boy joins in with an effortless virtuosity that is staggering. I turn on my pocket mini-disk recorder and capture half an hour of his playing. [Click on the picture, left.] Conversation during a brief break reveals that he is a conservatory student in the Ukraine and also a percussionist in the state symphony orchestra. The musicians are paid little and rarely, and so he, like others, must come to Berlin and busk. I wish that James Wood were still directing the percussion workshops at Darmstadt and could whisk him away on a scholarship.

The weather is sunny, almost warm. In one corner of the square a boy perhaps still in his teens unpacks a rickety xylophone without resonators and a cheap portable hi-fi. A music-minus-one accompaniment begins to distort the tiny loudspeakers and the boy joins in with an effortless virtuosity that is staggering. I turn on my pocket mini-disk recorder and capture half an hour of his playing. [Click on the picture, left.] Conversation during a brief break reveals that he is a conservatory student in the Ukraine and also a percussionist in the state symphony orchestra. The musicians are paid little and rarely, and so he, like others, must come to Berlin and busk. I wish that James Wood were still directing the percussion workshops at Darmstadt and could whisk him away on a scholarship.

Just to the west of Alexanderplatz across Spandauer Strasse is a pleasant little retreat into ersatz history called the Nikolaiviertel. Its centerpiece is the twin-spired Nikolaikirche, the oldest church in Berlin in loc

Just to the west of Alexanderplatz across Spandauer Strasse is a pleasant little retreat into ersatz history called the Nikolaiviertel. Its centerpiece is the twin-spired Nikolaikirche, the oldest church in Berlin in loc ation if not in structure. Around it are a modern fabrication of small pedestrian streets including a couple of restored old houses like enormous roccoco wedding-cake confections and a little Disneyland of quaint shops, including a 365-day-a-year Christmas Market with a whole suite of nutcrackers. Best of all is a very simple reconstruction of an old Berlin inn, Zum Nussbaum (At the sign of the Walnut Tree). Good beer, good plain food, and no tourist bullshit.

ation if not in structure. Around it are a modern fabrication of small pedestrian streets including a couple of restored old houses like enormous roccoco wedding-cake confections and a little Disneyland of quaint shops, including a 365-day-a-year Christmas Market with a whole suite of nutcrackers. Best of all is a very simple reconstruction of an old Berlin inn, Zum Nussbaum (At the sign of the Walnut Tree). Good beer, good plain food, and no tourist bullshit.

From here it’s a half-hour stroll back to Friederichstrasse and north to Chausseestrasse 125, where Berthold Brecht finally lived and died. [European addresses with the number after the street remind me of old spy movies.] Warren Leming [right], an American avant-garde theatrical producer who splits his working year between Chicago and Berlin, has promised to show me something of Brecht’s Berlin. This year is the centenary of his birth, and so the capitalists who now run the entire city are prepared to give him a modest degree of publicity. With luck, they’ll even keep the Berliner Ensemble solvent long enough to avoid a bad press.

We start with lunch in the basement of the Brecht House/Museum, a tasty goulash with crisp cabbagey sauerkraut (much better than the stodgy pap last night at Hardtke). The space is split into nooks and crannies like an old wine cellar, its walls covered densely with photos and mementos. One little room is closely lined on both sides with pairs of comfortable overstuffed seats for intimate tête-à-têtes. One could imagine it as a setting for Terrence Rattigan’s Separate Tables (now known to have originally had a gay protagonist), as it might be surreally adapted by Brecht and contrapuntally conflated by Kurt Weill.

With typical dramatic economy, Brecht died next door to the Dorotheenstädtische Friedhof, the small cemetery where he is buried along with half his entourage. (His window [right] overlooked it.) They share t he neighborhood with Hegel, Heinrich Mann, the neoclassical architects Schinkel and Schadow (they sound like a Yiddish comedy team), and the printer Lipfass, who assured himself immortality by inventing the round advertising kiosk. There’s Dialektik for you! Stoppard, get to work on your next play.

he neighborhood with Hegel, Heinrich Mann, the neoclassical architects Schinkel and Schadow (they sound like a Yiddish comedy team), and the printer Lipfass, who assured himself immortality by inventing the round advertising kiosk. There’s Dialektik for you! Stoppard, get to work on your next play.

FROM THE cemetary it’s a short walk south to the Berliner Ensemble. Set back from the Friederichstrasse on the edge of the Elbe and presided over by its patron saint [right], its generous premises are an endangered heritage from the Communist era. Living day-to-day and hand-to-mouth, it is a cultural embarrassment to the city’s new regime. Brecht once remarked that in America they revered his dramaturgy but rejected his politics; in Berlin it was the other way round. Today, in the New Berlin, both are considered irrelevant. In a twisted plot which Brecht would have wryly relished, the theatre’s land now belongs to Rolf Hochuth, the long-winded German docu-dramatist who attempted to take over the Ensemble. Rebuffed, he sought out the former Jewish owners of the property (now living in New York) and bought them out under new compensatory legislation, thus becoming the Ensemble’s landlord. The in-joke is that all of Brecht’s plays will suddenly prove to be, like Hochuth’s, four hours long.

IT’S NOW nine-thirty, and this evening’s concert has been so good that I deserve a splendid meal. Berlin’s finest restaurant is purported to be Bamberger Reiter, carefully nurtured for over a decade by Austrian chef Franz Raneburger. Reservations are normally essential, but service continues until 1a.m. and it’s now late enough to accommodate a lone diner. It’s the kind of restaurant I like, with a couple of fixed menus and no a la carte. Placing the card in front of me, the maitre de informs me that I may have any combination I like of any the items listed. How sensible! How un-Germanic! Un-American, for that matter—how often I’ve been told by a sullen waitress that I can have ham-and-eggs or bacon-and-eggs, but not bacon-and-ham-and-eggs because “It ain’t on the menu.”

IT’S NOW nine-thirty, and this evening’s concert has been so good that I deserve a splendid meal. Berlin’s finest restaurant is purported to be Bamberger Reiter, carefully nurtured for over a decade by Austrian chef Franz Raneburger. Reservations are normally essential, but service continues until 1a.m. and it’s now late enough to accommodate a lone diner. It’s the kind of restaurant I like, with a couple of fixed menus and no a la carte. Placing the card in front of me, the maitre de informs me that I may have any combination I like of any the items listed. How sensible! How un-Germanic! Un-American, for that matter—how often I’ve been told by a sullen waitress that I can have ham-and-eggs or bacon-and-eggs, but not bacon-and-ham-and-eggs because “It ain’t on the menu.”

But tonight I keep it simple by opting for the menu degustation. It starts promisingly with a terrine of goose liver: pure unadulterated flavor, accompanied by a sharp sauterne-based aspic which cuts through the rich foie gras like a knife. Then a generous portion of Atlantic lobster and scallops on marinated and lightly sautéed artichoke hearts. Then utterly fresh seabass, grilled and served with green asparagus, the tasty young sort Mary picks in our garden in season. Then succulent saddle of lamb: rib-thick eyes of meat, bone attached, pink, springy and almost fork-tender, served with stewed haricot beans worthy of a cassoulet.

And then the cheese cart arrives, as generously stocked as any in France. The young waiter identifies them all, in English, hardly stopping for breath, and receives a round of applause from the next table, a party of Americans. One of the cheeses is a really ripe crusty cantal—increasingly difficult to find, even in the Auverne.

Finally, after a “mouth-cleansing” clementine sorbet, there’s a delicious little soufflé of semolina and marinated blackberry, together with a scoop of almond ice cream. Price of the menu, exclusive of wine and service, is 195DM. Both cost and quality are about what one would expect in a 3-macaron French restaurant.

Conversation with the American table over coffee reveals that they have been staying at the very up-market Bristol Kampinski for three weeks and were sent here by the concierge. Is there any other restaurant in Berlin they’d recommend? “Not after you’ve eaten here!” is their unanimous verdict. Another wager, another jackpot. Who needs a lottery?

Saturday February 21

Today I have yet another Virgil to guide me through the purgatory of transitional Berlin. Terry Morgan is a vestigial remnant of the 60s: a folk singer who writes his own material. We met way back in 1978 when he came to my old studio at Marble Arch to record arrangements of some of his songs [You can listen to them here.], and we’ve kept in touch ever since. Every couple of years I get a phone call. Terry is back in London. Am I free? How about lunch? He comes around to the October Gallery, we open a bottle or two from my wine cellar, which is in the basement immediately adjacent to my studio (fatal, that!), and we take up our conversation where we had left off: “Meanwhile. . .”

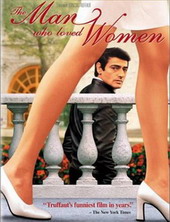

Terry could be the unashamed inspiration for the Trufaut film, The Man who Loved Women. His biological urges have served as the impetus for an endless series of love affairs, in which the word “love” is not merely a euphemism for lust. Unlike the macho conquistador, he talks—and listens—to women as intelligent human beings. Also atypically, he numbers ex-lovers among his continuing friends. Such beautiful creatures are not accustomed to being taken seriously.

Any woman who has passed through Terry’s bed will have received a liberal education. He picks up languages with the same facility with which he picks up lovers, and he is blessed—or cursed—with a virtually photographic memory. His conversation is peppered with names, dates, places, as though he had a direct cranial line to a reference library. He’s one of the few compulsive talkers I know to whom I compulsively listen.

In his (relative) old age, Terry has settled down. He has been living in Berlin with the same woman for the past four years. [It's now 2009 and they're still together.] (He has a pied a terre in Paris, but it is not, I gather, a Captain’s Paradise with yet another companion.) Today, for the first time in twenty years, I’ve been invited to spend the day with Terry and his Lady.

Dorte is twenty-four. A telephone conversation with her to set up today’s meeting shows her to be friendly, intelligent and witty, well beyond her years. (Four years with Terry is likely to have made some contribution.) I’m looking forward to meeting her. What sort of woman, exactly, does Terry find attractive?

His taste proves to be more elegantly restrained than I had imagined. Dorte is almost austerely beautiful: classic lines of face and figure, simple unremarkable clothes, no noticeable makeup. She is that rare combination, a profoundly beautiful woman with the personality of a plain woman: i.e., one who has had to learn that she cannot merely pose, but must be interesting and agreeable. If Terry has transformed her, he deserves credit for his tutelage; if he has merely left her unspoiled, he is to be commended for his restraint. “Dorte is in university, learning to care for old people,” says Terry, adding with typical light-hearted black humor, “That will come in handy.”

Terry’s plans for the morning begin with a walking tour. Following my own line of magnetic attraction, he leads us back towards the interface of West and East, the no-man’s-land of deep craters, the sites of foundations for yet-to-appear monuments to Pan-Germanic capitalism. Along the way are a scattering of modest reminders of what has brought u s to this point in history, including the still-surviving Gestapo headquarters in whose courtyard Stauffenberg and three other generals were executed for their abortive effort to blow up the Fuhrer. And nearby, in the midst of the furor of construction (Fuhrer—furor: an ironic euphony), lie the remnants of Hitler’s bunker, identifiable only by a random pile of stones [left] in the leveled dirt. (But you may be sure that Hitler’s new acolytes know exactly where it is located.)

s to this point in history, including the still-surviving Gestapo headquarters in whose courtyard Stauffenberg and three other generals were executed for their abortive effort to blow up the Fuhrer. And nearby, in the midst of the furor of construction (Fuhrer—furor: an ironic euphony), lie the remnants of Hitler’s bunker, identifiable only by a random pile of stones [left] in the leveled dirt. (But you may be sure that Hitler’s new acolytes know exactly where it is located.)

Hitler hated Berlin, a frivolous, uncooperative, unpredictable center of left-wing non-conformity. But it was necessary to take it seriously as Germany’s political and symbolic center of gravity. Burning the Reichstag must have given him a double delight, here in the stronghold both of the impotent republic and of the hated Marxist revolutionaries. Only the fanatical Prussians and the sentimental Bavarians were to be relied upon.

It is mid-day on a Saturday, but construction is still going on. People are trotting along the sidewalk as busily as though it were mid-week. But, aside from the intermittent noises of construction and of traffic, there is a preternatural silence. The crowds go voiceless about their business; nor do they scatter remnants of their passage. This is one vast construction site, and yet there is no mess, no litter. The effluvia of the entire city could be dumped into Trafalgar Square and scarcely noticed.

As usual, Terry has an explanation. In the 18th century, the Barón de Montesquieu had observed what he was convinced were differing rates of salivation between pigs north and south of the Alps. In the north, their glands seemed to be dried up and virtually inoperative; in the south, their saliva flowed freely. The explanation, he decided, lay in both the heat and the rays of the sun. These forces, for Montesquieu, were also operative upon humans, who were thus emblematic of their respective societies: northerners were dry, up-tight, easily subjected to authority, while southerners were spontaneous, undisciplined, impossible to govern. Which is why Roman traffic signals are merely ornamental, while Berliners wag their fingers at you if you presume to cross an empty street against a red light.

As usual, Terry has an explanation. In the 18th century, the Barón de Montesquieu had observed what he was convinced were differing rates of salivation between pigs north and south of the Alps. In the north, their glands seemed to be dried up and virtually inoperative; in the south, their saliva flowed freely. The explanation, he decided, lay in both the heat and the rays of the sun. These forces, for Montesquieu, were also operative upon humans, who were thus emblematic of their respective societies: northerners were dry, up-tight, easily subjected to authority, while southerners were spontaneous, undisciplined, impossible to govern. Which is why Roman traffic signals are merely ornamental, while Berliners wag their fingers at you if you presume to cross an empty street against a red light.

One intriguing aspect of central Berlin is the vast network of pipes leading above its principal streets and off into the distance. This, Terry explains, is because the center of Berlin, where so much deeply-dug construction is going on, was once a vast lake, and so the water must be carried away to where it can do no damage. How disappointing. I had imagined the pipes to be the channels through which the last vestiges of socialism were being siphoned off into the Black Sea.

IT HAS BEEN suggested that we go back to Dorte’s flat for lunch, as though there might be something in the fridge, maybe some bread and cheese. That’s fine with me. We take the S-Bahn to her neighborhood, formerly a stronghold of left-wing opposition to Hitler. Once we are in her light, airy apartment, having removed our shoes to protect the spotless carpeting—all this would be unattainable luxury for a British university student—I am left in the front room with the books and the view while mysterious noises emanate from the kitchen. Something serious appears to be going on, presaged by an elegantly laid dining table. Within a few minutes plates of smoked salmon appear on the table, together with huge bowls of lightly-dressed mixed salad sprinkled with roquefort, and a bottle of Pouilly Fuisse. Then come strips of chicken breast on toast, baked in the oven a la normande with crème fraiche. Finally, to polish it off, little dishes of crème caramel, not out of a packet. I’m being treated like visiting royalty. And what a spread for a young college girl to produce! Everything’s perfect. At twenty-four I wouldn’t have been able to identify the menu, let alone prepare it.

BACK TO the hotel to prepare for this evening. Then, after another satisfyingly perfect concert, a simple dinner. Our tenor Daryl expresses an interest in a Chinese meal and there’s a decent-looking place around the corner. Not expecting much of anything, I order hot and sour soup, followed by spicy prawns, Sezuan style. Both are generous and excellent—there must be well over a dozen large fresh prawns in the tasty but not overpowering sauce. Hovering in the air is the sound of a Chinese bamboo flute, its uniquely nasal overtones shimmering from its suspended membrane. Some selections are accompanied on the qin, the seven-string Chinese zither. It’s odd to be sitting here in Berlin, surrounded by Oriental sights and smells, and hearing once again, after thirty-five years, the instrument with which a pretty little flautist used to play me to sleep. But that, as Scheherezade would say, is another story.

BACK TO the hotel to prepare for this evening. Then, after another satisfyingly perfect concert, a simple dinner. Our tenor Daryl expresses an interest in a Chinese meal and there’s a decent-looking place around the corner. Not expecting much of anything, I order hot and sour soup, followed by spicy prawns, Sezuan style. Both are generous and excellent—there must be well over a dozen large fresh prawns in the tasty but not overpowering sauce. Hovering in the air is the sound of a Chinese bamboo flute, its uniquely nasal overtones shimmering from its suspended membrane. Some selections are accompanied on the qin, the seven-string Chinese zither. It’s odd to be sitting here in Berlin, surrounded by Oriental sights and smells, and hearing once again, after thirty-five years, the instrument with which a pretty little flautist used to play me to sleep. But that, as Scheherezade would say, is another story.

Sunday February 22

The last concert has arrived too quickly. How long would it take me to grow bored with such easy perfection? Would it become an embarras de richesse? A.J. Liebling has written brilliantly of the lack of dietary scope which is imposed on those who grow up with so much money that their taste is formed by the blandly expensive, such foods as fillet of sole or of beef which are so highly valued precisely because they never challenge or give offense. He sums it up in a short passage that I’ve transcribed into the back of my address book: In learning to eat, as in psychoanalysis, the customer, in order to profit, must be sensible of the cost.

The last concert has arrived too quickly. How long would it take me to grow bored with such easy perfection? Would it become an embarras de richesse? A.J. Liebling has written brilliantly of the lack of dietary scope which is imposed on those who grow up with so much money that their taste is formed by the blandly expensive, such foods as fillet of sole or of beef which are so highly valued precisely because they never challenge or give offense. He sums it up in a short passage that I’ve transcribed into the back of my address book: In learning to eat, as in psychoanalysis, the customer, in order to profit, must be sensible of the cost.

This Sunday morning concert is to be transmitted to Japan for live TV broadcast. That will put it out at 8 p.m., evening prime time. Though it’s billed as a “youth concert”, the audience is not noticably younger than the others. With the hall about 80% full, this is the only one not to sell out completely.

The Berio Sinfonia performance this morning is perhaps the best of the four. All the performers are now so confident of what they and each other are doing that they can afford to play around a bit, to take chances. The most nail-biting instrumental passages, in which, the better the ensemble, the more obvious is any single imperfection, have become positively lyrical, a perfect example of the art that conceals art. Is this the way that Berio heard the work in his head, or did he envisage an eternal struggle? He must know that the history of art, as of technology, is a tale of the impossible made easy.

This morning Electric Phoenix all stay on for the second half of the program, the Mahler 2nd symphony. With the extra rehearsal time, Simon has taken full advantage of the skill of the orchestra and the clarity of the hall, so that the work becomes almost chamber music in its precise deliniation—the unambiguous exactitude of an etching rather than the grand but vague gestures of a vast romantic mural. Christine Schaefer, the soprano who has been engaged for the fourth movement, is so young and so delicately beautiful that I can’t imagine her coming to terms with this music; but, as soon as she opens her mouth, I am reminded of the simple purity which the great Arlene Auger brought to Schubert lieder. There is no posturing, no pretense. We enjoy heavenly pleasures/And leave the earthly behind, she sings. And I believe her.

When it is all sadly, regretfully over—There is no music on earth/That can be compared with ours—the audience bring the conductor and soloist back for curtain call after curtain call. At a signal from Simon, the orchestra arise, shake hands with their neighbors, and depart. But the audience then start a slow hand-clap and will not even begin to leave the hall until the two shimmering stars have returned one last time to the now empty stage. Mahler must be smiling quietly in his grave. We all know that we have shared a unique experience. Surely that's what art is all about.

©1998 John Whiting

![]()