![]()

Architecture for

architecture’s sake

The ancient city of Prague is as multifaceted as its most famous author, Franz Kafka. The many centuries of its political history have left behind architectural jewels of every major genre, from Romanesque to Art Nouveau. In the 20th century, its two lucky accidents were the absence of obliterative bombing and a post-war poverty which prevented it from levelling its treasures and erecting those high rise monuments to money and modernity which befoul every other major city.

The latter ble ssing cannot be overstressed. In studying the history of the great baroque organs, I learned that those that were still extant owe their survival to the fact that in the 19th century, all the churches that could afford it were ripping out their puny little two-manuals and installing behemoths that could do justice to the monumental works of Caesar Franck and Sigfrid Karg-Elert. Their poor country cousins, however, were stuck with what they had. (This is the splendid example in Our Lady before Tyn, which overlooks the Old Town Square.)

ssing cannot be overstressed. In studying the history of the great baroque organs, I learned that those that were still extant owe their survival to the fact that in the 19th century, all the churches that could afford it were ripping out their puny little two-manuals and installing behemoths that could do justice to the monumental works of Caesar Franck and Sigfrid Karg-Elert. Their poor country cousins, however, were stuck with what they had. (This is the splendid example in Our Lady before Tyn, which overlooks the Old Town Square.)

When Mary and I were in Prague in 1991, our guide assured us that the restoration that was about to take place would respect the city’s architectural integrity. But I was fearful—I had seen so many European cities in which the restoration had been localized and piecemeal, interspersed with modern horrors which required that, in order to enjoy the greatest monuments, you had to wear blinkers.

But the enormous scale and utter integrity of Prague’s restoration became  dramatically evident during a slow boat trip along the city’s shore on our first morning, passing under its three most famous bridges. A mid-city river view is the most revealing way to see what major new architecture has been allowed to overshadow or replace its predecessors. Prague passed this test with flying buttresses. There were no skyscrapers, no oversized mantle clocks, no packing cases, no giant Lego sets, no architects’ wet dreams—just a succession of dignified, beautiful, functional, historical buildings, all nestled side by side in easy harmony. I did not relish returning to London, or anywhere else.

dramatically evident during a slow boat trip along the city’s shore on our first morning, passing under its three most famous bridges. A mid-city river view is the most revealing way to see what major new architecture has been allowed to overshadow or replace its predecessors. Prague passed this test with flying buttresses. There were no skyscrapers, no oversized mantle clocks, no packing cases, no giant Lego sets, no architects’ wet dreams—just a succession of dignified, beautiful, functional, historical buildings, all nestled side by side in easy harmony. I did not relish returning to London, or anywhere else.

-0-

That morning we had spent a couple of hours walking around the grounds  ofPrague Castle and St Vitus Cathedral. The latter is the largest church in the Czech Republic and a magnificent structure that was slowly constructed under a succession of regimes and master builders, beginning in the high French gothic style in the 14th century. For several centuries it was left half-finished, finally to be completed in the neo-gothic style in the 20th century, including some splendid modern stained glass windows. One can easily spot the succession of styles but, like the city of Prague itself, it possesses a harmony that draws you into its utter magnificence.

ofPrague Castle and St Vitus Cathedral. The latter is the largest church in the Czech Republic and a magnificent structure that was slowly constructed under a succession of regimes and master builders, beginning in the high French gothic style in the 14th century. For several centuries it was left half-finished, finally to be completed in the neo-gothic style in the 20th century, including some splendid modern stained glass windows. One can easily spot the succession of styles but, like the city of Prague itself, it possesses a harmony that draws you into its utter magnificence.

Considering the crowds of tourists in which we were swept along, this was quite an accomplishment! It reminded me of our cruise visit years ago to the Cathedral of Santiago de Compostela, in which we were jammed shoulder to shoulder with hundreds of footsore pilgrims. In Prague, once inside the cathedral, the nave and side isles were only accessible in a separate guided tour and so, working my way up to the barrier at the rear of the nave, I was able to view the magnificent vaulting and the distant sanctuary in solitary contemplation.

Outside again, we could appreciate the massive structure’s archetypal gothicity. There’s a lot of false gold in the colour scheme, but the 14th century Golden Portal is covered with lots of the real thing. It’s not as impressive as its imitations unless you stand directly in front with the sun coming from the right angle, and then it’s overpowering. All that glistens . . .

Outside again, we could appreciate the massive structure’s archetypal gothicity. There’s a lot of false gold in the colour scheme, but the 14th century Golden Portal is covered with lots of the real thing. It’s not as impressive as its imitations unless you stand directly in front with the sun coming from the right angle, and then it’s overpowering. All that glistens . . .

A café near the castle’s eastern gate, with a young male statue by Miloš Zetin in the courtyard, is a favourite refreshment point for both culinary and carnal appetites. Grasping the statue at a certain point is supposed to bring good luck, its nature unspecified. Ladies -- and I daresay a few gentlemen -- were constantly being thus photographed; Mary politely declined my invitation.

Our two hour walk around the castle grounds concluded with a long gingerly descent down a steep path to our waiting bus. By its end, I was feeling as footsore and weary as a Santiago da Compostella pilgrim.

-0-

We went back the next day to the Steinberg Palace just outside the castle’s main gate. The first floor exhibition halls house the famous works of 14th - 16th century art that come from the Konopište Castle collection of Archduke Franz Ferdinand d´Este. It is striking that these do not consist of paintings glorifying war and those who wage it, but are a wealth of great depictions of common people and common life. They might have been chosen, not by His Grace, but by an astute art critic. It’s ironic that he should be most famous for the fact that his sudden demise sparked the Great War. Nothing in his life became him less than the leaving of it.

-0-

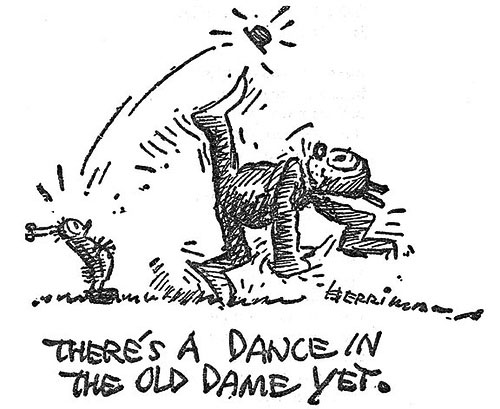

On the top floor, side by side in a small side room were two small sculptures by Simon Troger, an 18th century German ivory carver. The two lively figures are called Old Man Dancing and Old Woman Dancing. They caught and held my attention so irrevocably that I photographed them as a perpetual encouragement for my old age.

Don Marquis caught the spirit in mehitabel dances with boreas, in which archy the cockroach types a poem about his friend mehitabel the cat. He accomplishes this remarkable feat by diving head first onto each key (hence no upper case).

well boss i saw mehitabel

last evening

she was out in the alley

dancing on the cold cobbles

while the wild december wind

blew through her frozen whiskers

and as she danced

she wailed and sang to herself

uttering the fragments

that rattled in her cold brain

in part as follows

whirl mehitabel whirl

spin mehitabel spin

thank god you re a lady still

if you have got frozen skin

blow wind out of the north

to hell with being a pet

my left front foot is brittle

but there’s life in the old dame yet

dance mehitable dance

caper and shake a leg

what little blood is left

will fizz like wine in a keg

wind come out of the north

and pierce to the guts within

but some day mehitabel’s guts

will string a violin