![]()

Living a Normal Life

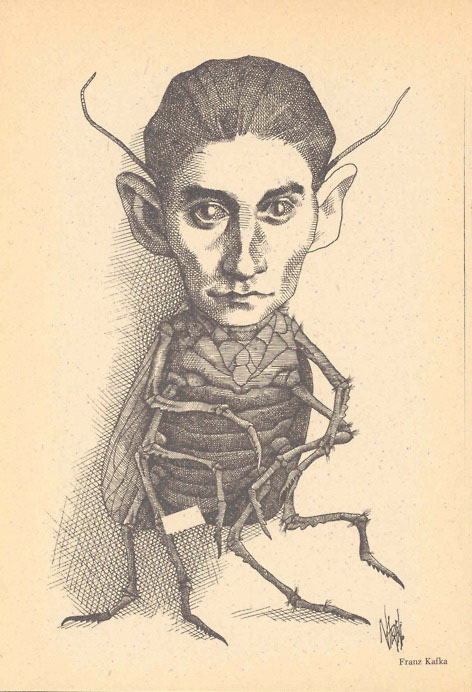

If Franz Kafka comes to occupy your brain, then you begin to look through his eyes at what is supposed to be the normal world. His point of view, i.e. the exact perspective from which he observed it, was determined by the fact that, like Charles Ives and Wallace Stevens, his day job was as an insurance executive. (This was in the days when insurance was a benevolent mutual protection against economic disaster.)

Kafka was a well-respected insurance lawyer whose work included investigating and assessing compensation for personal injury to industrial workers, including lost fingers and limbs. In those days before legally enforced safety measures, such mishaps were plentiful indeed. What a cornucopia of morbidity! Think of Melville’s Bartleby and all those lost letters: “Ah, Bartleby! Ah, humanity!”

Kafka left all of his major literary work in fragments which he instructed his best friend, Max Brod, to destroy. But contrary to Kafka’s wishes, Brod assembled, completed and published them, thus giving his own form to Kafka’s formlessness. He also wrote a biography which remains the primary source on the details of Kafka's life. How paradoxical that an author who was so spasmodic in his literary output should have had such a profound influence on so many others from so many countries and cultures who came to see through his eyes and speak as with his voice. Is it not only the content of Kafka's writing but also this creative paradox itself that has revealed to them how Sisyphean is the task of making sense of an insane world?

As well as those who have shared Kafka’s perspective, there are innumerable critics who have set out to make explicit his deliberate ambiguities, but who end up only revealing their innermost biases and contradictions. Listening to the vociferous arguments among Kafka’s various interpreters is to witness the self-revelations of a host of introverts.

As well as those who have shared Kafka’s perspective, there are innumerable critics who have set out to make explicit his deliberate ambiguities, but who end up only revealing their innermost biases and contradictions. Listening to the vociferous arguments among Kafka’s various interpreters is to witness the self-revelations of a host of introverts.

As our human world grows ever more insane, Kafka and his fellow surrealists reveal a supernal rationality, an observing eye at the center of a whirling chaos. A distinguished literary friend emailed to me recently, “Yes, who would have thought that Kafka and Beckett count as optimists?”

-0-

It was in the aftermath of America’s quintessentially Kafkaesque mid-term elections that Mary and I visited Prague’s Franz Kafka Museum on our last day. A crowd of tourists and a guide were just arriving, but not for Kafka. In the courtyard is David Cerny's, “Piss”, a statue of two naked men standing in a shallow pool, their torsos swivelling slowly back and forth. Fully equipped, they are polluting the water, which on closer examination proves to be in the shape of Czechoslovakia. They are, says the sculptor, the country’s high officials, pissing on the populace. Transport them to Britain or America, and change the pool's shape...

It was in the aftermath of America’s quintessentially Kafkaesque mid-term elections that Mary and I visited Prague’s Franz Kafka Museum on our last day. A crowd of tourists and a guide were just arriving, but not for Kafka. In the courtyard is David Cerny's, “Piss”, a statue of two naked men standing in a shallow pool, their torsos swivelling slowly back and forth. Fully equipped, they are polluting the water, which on closer examination proves to be in the shape of Czechoslovakia. They are, says the sculptor, the country’s high officials, pissing on the populace. Transport them to Britain or America, and change the pool's shape...

The museum’s website , which is in Czech, doesn’t offer any translations, even into German, Kafka’s own literary language, but it includes a rather crude little animated cartoon with English captions and jazzy, carefree background music. But in the bookshop across the courtyard there is an informative and evocative pamphlet in English (click HERE), which I didn’t see in either German or Czech. Oddly, none of Kafka’s own work was on sale, in any language.

The museum itself proved to be the most remarkable such memorial devoted to a single author that we had ever encountered. It contained not only the usual documents and objects, but incorporated an elaborate evocation of the civic and psychological ambience of the city that had nurtured, tormented and ultimately inspired him. As we moved around the exhibits there were surreal Dali/Buñuel-like video sequences  with atmospheric music/sound accompaniments which spatially cross faded as we progressed from one to another. In one room there was a complex cubicle structure which purported to be the electro-mechanical Designer controlling the Harrow of the torture machine in Kafka’s penal colony. What provocative nomenclature! It was impossible to look at it and not think of the CIA's ingenious efforts to extract -- nay, to invent! -- information from the many thousands it has accused of terrorism, the full report of which is still being withheld.

with atmospheric music/sound accompaniments which spatially cross faded as we progressed from one to another. In one room there was a complex cubicle structure which purported to be the electro-mechanical Designer controlling the Harrow of the torture machine in Kafka’s penal colony. What provocative nomenclature! It was impossible to look at it and not think of the CIA's ingenious efforts to extract -- nay, to invent! -- information from the many thousands it has accused of terrorism, the full report of which is still being withheld.

In a case in the next room was a first edition of Kafka’s A Country Doctor, one of the few stories published during his lifetime. What memories it held for me! Half a century ago, it was one of the first tales of the supernatural that Erik Bauersfeld and I had dramatized for radio in the now legendary series, Black Mass. As always, Erik’s adaptation was meticulously close to the original, both in text and in atmosphere. One of our most frequently used voices was that of Bernard Mayes, who was to become something of a celebrity in his own right. Alas, I had just had word from Erik that he was no longer with us. You can listen to Kafka's surrealistic little story HERE.

In a case in the next room was a first edition of Kafka’s A Country Doctor, one of the few stories published during his lifetime. What memories it held for me! Half a century ago, it was one of the first tales of the supernatural that Erik Bauersfeld and I had dramatized for radio in the now legendary series, Black Mass. As always, Erik’s adaptation was meticulously close to the original, both in text and in atmosphere. One of our most frequently used voices was that of Bernard Mayes, who was to become something of a celebrity in his own right. Alas, I had just had word from Erik that he was no longer with us. You can listen to Kafka's surrealistic little story HERE.

The final exit from the exhibition was down a long red-lit staircase into a world which seemed less real than that which we had just left. A couple of nights later, back home in the comfort of our living room, we would watch Soderbergh’s remarkable Kafka (1991) which someone had put up on YouTube. It has been roundly condemned on various grounds by the Kafka experts, but we found it to be like a continuation of our museum visit. How long before the copyright police take it down?

-0-

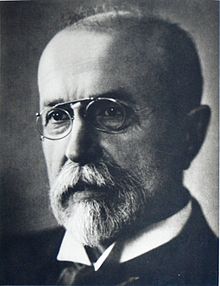

Feeling in need of refreshment after our museum visit, we went into a small café across the courtyard next to the bookstore. While we were sipping our drinks a young man came over to our table and asked us how we had liked the museum. We were suitably enthusiastic. He then introduced himself as a tour guide and confessed that he’d come to our table because I reminded him of Tomáš Masaryk, Czechoslovakia’s first President. What a burden of responsibility! Kafka’s Prague, his “little mother with claws”, had followed me out of the museum and sunk them into my calf.

Feeling in need of refreshment after our museum visit, we went into a small café across the courtyard next to the bookstore. While we were sipping our drinks a young man came over to our table and asked us how we had liked the museum. We were suitably enthusiastic. He then introduced himself as a tour guide and confessed that he’d come to our table because I reminded him of Tomáš Masaryk, Czechoslovakia’s first President. What a burden of responsibility! Kafka’s Prague, his “little mother with claws”, had followed me out of the museum and sunk them into my calf.