![]()

5 August 2006 Last month, after helping to judge a group of international food awards, I took away several almost-full bottles. One was a single estate extra virgin olive oil. When I got home, I learned from the label that it was from Marjeyoun, in “the ancient olive growing region of southern Lebanon.” It was rich and fruity, with a well-rounded flavor that was a delight to the palate, an “exeptionally low level of acidity, less that 0.5%”, and a slight pleasant catch of bitterness at the back of the throat.

5 August 2006 Last month, after helping to judge a group of international food awards, I took away several almost-full bottles. One was a single estate extra virgin olive oil. When I got home, I learned from the label that it was from Marjeyoun, in “the ancient olive growing region of southern Lebanon.” It was rich and fruity, with a well-rounded flavor that was a delight to the palate, an “exeptionally low level of acidity, less that 0.5%”, and a slight pleasant catch of bitterness at the back of the throat.

I’ve always been fond of Lebanese food. Among London restaurants serving Middle Eastern cuisine, theirs are some of the most sophisticated, generous and hospitable. The meze embodies an act of sharing in which the dishes are passed around like an informal menu dégustation—a foodie’s delight!

To accompany them, Lebanese wines are a notable pyramid at whose apex is the legendary Chateau Musar. Its grapes have sometimes been harvested within sound of gunfire. Now the weapons of war have been unleashed again, this time with the grim sophistication that another decade of human ingenuity has been able to devise. Lebanon is once more in the world news and the region that produced my little bottle has been under attack, then occupation. Robert Fisk visited its hospital and Middle East News reports that the Israeli army “had taken 400 Lebanese policemen and civilians hostage in the Marjeyoun barracks.”

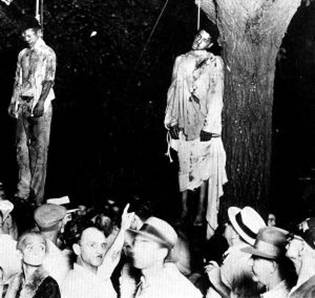

There is no news of the olive trees. Will they be plowed under, like the hundreds of acres of ancient groves in Palestine, in case they might harbor Arab snipers? Olives and grapes—the fruits of peace and conviviality, paradoxically exported from a war-ravaged country. I thought of the bitter fruit once harvested in the American South. In 1937 Abel Meeropol, a New York Jewish schoolteacher, saw a photograph of the lynching of Thomas Shipp and Abram Smith. It haunted him for days and he wrote a poem, “Strange Fruit”, which was published in the New York Teacher.

That might have been the end of it, but Meeropol saw Billie Holiday perform at Café Society and impulsively showed her his poem. She “dug it right off” and worked with her accompanist Sonny White to turn it into a song which ultimately made it into the charts. It was duly denounced by Time Magazine as “a prime piece of musical propaganda” for the NAACP. Plus ça change.

Southern trees bear strange fruit,

Southern trees bear strange fruit,

Blood on the leaves and blood at the root,

Black bodies swinging in the southern breeze,

Strange fruit hanging from the poplar trees.

Pastoral scene of the gallant south,

The bulging eyes and the twisted mouth,

Scent of magnolias, sweet and fresh,

Then the sudden smell of burning flesh.

Here is fruit for the crows to pluck,

For the rain to gather, for the wind to suck,

For the sun to rot, for the trees to drop,

Here is a strange and bitter crop.

Thomas Shipp and Abram Smith, August 7, 1930

You may object that it’s grossly unfair to equate the Southern lynchings with the collateral damage of Israel’s “fight for survival”. Yes indeed. There were “2805 [documented] victims of lynch mobs killed between 1882 and 1930 in ten southern states.”* , while Israeli bombs and missiles have been able to purge well over 1300 Lebanese in four weeks. At that rate they could outstrip the rednecks' half-century record in about two-and-a-half months.

That's because the Old Boys were old-fashioned artisans. They selected their victims one by one and dispatched them with considerable ceremony, whereas the final solution of the Lebanese problem has been undertaken with the techniques of mass production/destruction that Adolf Hitler learned so well from his good friend Henry Ford. Meanwhile, if your latest bottle of Lebanese olive oil has a reddish tinge, don’t even ask.

16 August 2006 The Irate Codger responds:

“O for a beaker full of the warm South”

War is always horrible, but never more so than when it smashes up beautiful Mediterranean countrysides. Take a Gauguin Provencal landscape with its ochers and umbers, its olives and pale blues; contemplate its stillness; then go berserk, slash it with a knife, smear it with ugly swipes of red paint...

During Milosovic's campaigns a decade ago I'd marvel at the beauty of the Balkan mountains and valleys and the ancient towns, towns deliberately, methodically destroyed. And that beautiful 14th century bridge in Mostar, blown up in a second (and now happily restored).

How bloody-minded human beings are, and none, recently, more conspicuously than the Jews. Not enough that they should smash Gaza to bits, they decided that Lebanon must be destroyed for capturing two soldiers (and fine young men they were, I'm sure).

Your bottle of olive oil is a heartbreaking and enraging symbol. I think you go rather far over the top in speaking of a final solution to the Lebanese problem (as you meant to do, I know: “If this be anti-Semitism, then make the most of it!,” to paraphrase Patrick Henry).

But this occurred to me early on in the wanton destruction of south Beirut: “This reminds me of Warsaw in September, 1939.” Then I thought, “Isn't that rather extreme?” Then, “No, I don't think it is.” I'm not comparing Beirut to what RAF Bomber Command did to Hamburg in 1943, or the US Air Force to Tokyo in 1945 (tens of thousands dead in Hamburg, 100,000 in Tokyo). No, the Luftwaffe bombing of Warsaw was quite modest in scale compared to those operations. Stukas and Heinkels didn't have the bombing capacities of Wellingtons and B-29s. One difference: the Israelis after the first operations did drop leaflets warning the inhabitants to flee [and then bombed the convoys. Ed.], which was more than the Germans did for the Poles. That aside, I think the comparison stands. An atrocity is an atrocity. And this one was especially vicious because from a military standpoint wholly needless. There was never any relationship between any possible Israeli “war aim” and the destruction of Beirut.

Let's see, to Bush's credit we now have Baghdad, New Orleans, and Beirut. What's next? I think Tehran. As Bush said, Iran must face the music “in weeks, not months.” September sounds about right. As Andrew Card once said, “You don't introduce a new model in August, but September.” Let the bombing resume!

23rd August 2006 The Denouement

Robert Fisk: Untold story of the massacre of Marjayoun leaves blame on both sides of the border The Independent (London) 23 August 2006

There are few marks on the road where the missiles hit the innocents of Marjayoun. But there are the memories of what happened immediately after the Israeli airstrike on the convoy of 3,000 people after dark on 11 August: a 16-year old Christian girl screaming "I want my Daddy" as her father's mutilated body lay a few metres away from her; the town mukhtar discovering that his wife, Collette, had been decapitated by one of the Israeli missiles; the Lebanese Red Cross volunteer who went into the darkness of wartime Lebanon to give water and sandwiches to the refugees and was cut down by another missile, and whose friends could not reach him to save his life.

There are those who break down when they recall the massacre at Joub Jannine - and there are the Israelis who gave permission to the refugees to leave Marjayoun, who specified what roads they should use, and who then attacked them with pilotless, missile-firing drone aircraft. Five days after being asked to account for the tragedy, they had last night still not bothered to explain how they killed at least seven refugees and wounded 36 others just three days before a UN ceasefire came into effect.

It is one of the untold stories of the Israeli-Hizbollah war; there are others - infinitely more bloody - but the ultimate tragedy of these largely Christian refugees involved a raft of Lebanese officers and ministers, the Prime Minister of Lebanon, the US ambassador and the Israeli Defence Ministry.

It all began on 10 August when the Israelis staged a small ground offensive into Lebanon after a month of massive bombing of Lebanese villages in the south. Brig-Gen Adnan Daoud, commanding a mixed force of 350 Lebanese paramilitary police and soldiers at the barracks in the pretty Christian town of Marjayoun, found a man at the gate at 9am, an Israeli officer calling himself Col Ashaya. Brig-Gen Daoud, whose men were not fighting the Israelis, called the Lebanese Interior Minister, Ahmad Fatfat, who "endorsed" - Fatfat's word - Daoud's decision to let him in. "Ashaya" spent four hours looking round the barracks to assure himself that there were no Hizbollah members there. Then he left. Daoud put a white flag on the guardhouse.

But at 4pm that afternoon, an Israeli tank unit approached the barracks and started to shoot their way in. Daoud was again told by Fatfat to let in the Israelis who, according to Daoud, informed him that "we are the occupiers and we are in charge". An Israeli officer then locked Daoud into a room.

Thousands of Christians in Marjayoun now feared for their lives. According to several aid workers, Hizbollah were firing rockets from behind the town's hospital, which was immediately abandoned by the Lebanese Red Cross. The inhabitants believed, with good reason, that Hizbollah's missiles would be redirected from Israel on to Marjayoun itself now that the town had been taken over by Israeli troops and tanks.

Locked in his room, Daoud now called Fatfat again and Fatfat called the Lebanese Prime Minister, Fouad Siniora, who, by chance, was talking to the US ambassador to Beirut, Jeffrey Feltman. Feltman - either via the State Department or directly to the US embassy in Tel Aviv - told his diplomats to call the Israeli Defence Ministry; and they swiftly replied that there should be no Israeli troops in Daoud's barracks. But the Israelis in Marjayoun refused to believe what Daoud told them.

Marjayoun's inhabitants, however, were now in a state of panic and Daoud called Fatfat at 7pm to start arranging for a refugee convoy north from Marjayoun to Beirut. The Lebanese government, according to Fatfat, called the United Nations command in southern Lebanon at 5am the next day, 11 August, to seek clearance from the Israelis to allow the thousands of refugees to be convoyed north. The UN, according to the government in Beirut, subsequently notified Gen Abdulrahman Shaiti, assistant to the head of Lebanese military intelligence, that the convoy had permission from the Israelis to travel.

Two UN armoured vehicles, crewed by Indian troops, subsequently turned up in Marjayoun to find at least 3,000 people, including Shia Muslim refugees from the surrounding, devastated villages, waiting to leave. "We had a total agreement that they would go out to the Bekaa [Valley] from [Alain] Pellegrini [the UN commander]," Fatfat says. "The road was also agreed." But there were delays. Part of the road ahead had been heavily bombed and had to be repaired. It was 4pm before the convoy crept slowly out of Marjayoun, Daoud's 350 soldiers in the lead. The UN vehicles then abandoned the convoy at Hasbaya, the northern limit of UN operations, leaving the refugees dangerously exposed. The UN had already warned the Lebanese authorities that it was late for the convoy to leave.

"They went so slowly, I was enraged," a relief worker recalls. "People at friendly villages would come out and give the refugees food and water and want to talk to them and people would stop to greet old friends as if this was tourism. The convoy was only going at five miles an hour. It was getting dark." The 3,000 refugees now trailed up the Bekaa after nightfall and were approaching the ancient Kifraya vineyards at Joub Jannine when disaster struck them at 8pm.

"The first bomb hit the second car," Karamallah Dagher, a reporter for Reuters, said. "I was half way back down the road and my friend Elie Salami was standing there, asking me if I had any spare gasoline. That's when the second missile struck and Elie's head and shoulders were blown away. His daughter Sally is 16 and she jumped from the car and cried out: 'I want my Daddy, I want my Daddy.' But he was gone." Speaking of the killings yesterday, Dagher breaks down and cries. He tried to carry his arthritic mother from his own car but she complained that he was hurting her so he put her back in the passenger seat and sat beside her, waiting for a violent death which mercifully never came. But it arrived for Collette Makdissi al-Rashed, wife of the mukhtar, who was beheaded in her Cherokee jeep, and for a member of the Tahta family from from Deir Mimas, and for two other refugees, and for a Lebanese soldier and for 35-year-old Mikhael Jbaili, the Red Cross volunteer from Zahle, who was blasted into the air when a rocket exploded behind him.

"There was panic," the Marjayoun mayor, Fouad Hamra, said. "Many people drove away. They had a clearance; everything should have been OK. If Hizbollah was supposed to be carrying weapons at night, they would have been travelling in the opposite direction!"

Who flew the drones? An Israeli soldier of the invasion force? A nameless officer in the Israel Defence Ministry in Tel Aviv? The Israelis knew a civilian convoy was on the road. Yet they sent their pilotless machines to attack it. Why? Last night, the Israeli Defence Ministry had not responded to inquiries from reporters who asked for the answer last Friday.

18th September 2006 Stranger Fruit: The Deadly Harvest The (London) Independent, 18 September 2006

The war in Lebanon has not ended. Every day, some of the million bomblets which were fired by Israeli artillery during the last three days of the conflict kill four people in southern Lebanon and wound many more.

The casualty figures will rise sharply in the next month as villagers begin the harvest, picking olives from trees whose leaves and branches hide bombs that explode at the smallest movement. Lebanon's farmers are caught in a deadly dilemma: to risk the harvest, or to leave the produce on which they depend to rot in the fields....

Some Israeli officers are protesting at the use of cluster bombs, each containing 644 small but lethal bomblets, against civilian targets in Lebanon. A commander in the MLRS (multiple launch rocket systems) unit told the Israeli daily Haaretz that the army had fired 1,800 cluster rockets, spraying 1.2 million bomblets over houses and fields. "In Lebanon, we covered entire villages with cluster bombs," he said. "What we did there was crazy and monstrous." ...

Frederic Gras, a de-mining expert formerly in the French navy, who is leading the MAG teams in Yohmor, says: "In the area north of the Litani river, you have three or four people being killed every day by cluster bombs. The Israeli army knows that 30 per cent of them do not explode at the time they are fired so they become anti-personnel mines."

Why did the Israeli army do it? The number of cluster bombs fired must have been greater than 1.2 million because, in addition to those fired in rockets, many more were fired in 155mm artillery shells. One Israeli gunner said he had been told to "flood" the area at which they were firing but was given no specific targets. M. Gras, who personally defuses 160 to 180 bomblets a day, says this is the first time he has seen cluster bombs used against heavily populated villages. [emphasis mine]

An editorial in Haaretz said that the mass use of this weapon by the Israeli Defence Forces was a desperate last-minute attempt to stop Hizbollah's rocket fire into northern Israel. Whatever the reason for the bombardment, the villagers in south Lebanon will suffer death and injury from cluster bombs as they pick their olives and oranges for years to come.

Dr. Ran HaCohen is a university teacher in Israel and a literary critic for the Israeli daily Yedioth Achronoth.Israeli liberal intellectuals are against war….There is just one minor exception, though: the present war, every present war, which they always support.

©2006 John Whiting

2009 Events in Gaza make all of the above a mere dress rehearsal.