“There is no better Lyonnais bistro in Paris than this time-mellowed place,” says Frommer’s Paris 2005. Lyon’s legendary appetite has traditionally separated the gourmets from the gourmands. Samuel Chamberlain wrote half a century ago that its gastronomic abundance “led to a double phenomenon—superlative cooking and gargantuan appetites….Your average Lyonnais is a person with an impressive ability to absorb good food—in abundance.” Waverley Root, writing at about the same time, anticipated a more modern perspective: “The cooking of Lyons fits the character of the city—it is hearty rather than graceful, and is apt to leave you with an overstuffed feeling.”

At Aux Lyonnais, those of modest appetite need fear no discomfort. This venerable bistro has been taken over by the omnivorous restaurateur Alain Ducasse, together with Thierry de la Brosse of L’Ami Louis, the bistro that pioneered the pairing of massive portions with massive expenditure. Aux Lyonnais is more modest in all respects: flavors are succulent but genteel, quantities ample but unagressive, and the cost lies between bistro-plus and Michelin-minus. The Lyonnais lion has been made to roar as soft as any sucking dove.

At Aux Lyonnais, those of modest appetite need fear no discomfort. This venerable bistro has been taken over by the omnivorous restaurateur Alain Ducasse, together with Thierry de la Brosse of L’Ami Louis, the bistro that pioneered the pairing of massive portions with massive expenditure. Aux Lyonnais is more modest in all respects: flavors are succulent but genteel, quantities ample but unagressive, and the cost lies between bistro-plus and Michelin-minus. The Lyonnais lion has been made to roar as soft as any sucking dove.

Ducasse’s web site identifies it as a “Parisian version of a Lyonnais bouchon”. Parisian indeed. In Lyon, the buchons were presided over, not by chef/entrepreneurs with far-flung empires, but by formidable grandmères. Writes Chamberlain, his tongue firmly planted in his cheek,

At first sight, you wonder if a restaurant has any possible chance of fame and fortune here unless it is run by somebody’s dear old mother…Nowhere have I been able to find a Lyonnais restaurant run by Le Père anybody. It seems to be woman’s domain, to be passed on to daughters, and maybe sons-in-law.

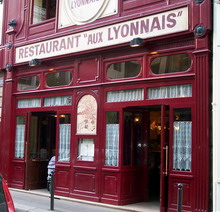

INSIDE and out, Aux Lyonnais seems preserved in amber. The Third Republic interior by Louis Majorelle, dating from 1890, has been altered only slightly so as to incorporate a zinc bar scavenged from another historic bistro not so fortunate as to acquire a patron. We found the waitstaff to be as welcoming as the décor—all seemed to speak English fluently and cordially, thus making an English carte superfluous. Bilingual staff appeared to be essential; most of the diners around us were speaking with the sort of clear American voice that carries intelligibly, without shouting, across a crowded room.

INSIDE and out, Aux Lyonnais seems preserved in amber. The Third Republic interior by Louis Majorelle, dating from 1890, has been altered only slightly so as to incorporate a zinc bar scavenged from another historic bistro not so fortunate as to acquire a patron. We found the waitstaff to be as welcoming as the décor—all seemed to speak English fluently and cordially, thus making an English carte superfluous. Bilingual staff appeared to be essential; most of the diners around us were speaking with the sort of clear American voice that carries intelligibly, without shouting, across a crowded room.

Our sleek handsome sommeliere [!] also seemed American, both in her accent and her attitude. After consulting the wine list, I had decided on a moderately priced Merlin Moulin à Vent 2003, an excellent Beaujolais.

“It is very full-bodied,” she announced with the authority of a Wellesley co-ed instructing a half-witted child. “The Brouilly would be a better match for your menu.”

I dug my heels in. “I know the Moulin, it is a favorite of mine.”

“Yes, but you must learn to be adventurous!” she persisted without a moment’s hesitation.

Was I hearing correctly, or was I hallucinating Brenda Patimkin, stepping off the screen of Goodbye Columbus? An ancient sommelier at Le Buerehiesel in Strasburg once ventured to point out to me that the Gewürztraminer I had ordered with my tasting menu was not dry, but when I assured him that I knew this he retreated behind a proper, “Very good, sir.”

Never mind—it was an amusing encounter, it was the only false note of the evening, and when I eventually got my Moulin, it was ripe and well-rounded. I sipped it with evident pleasure whenever our Ali MacGraw look-alike passed our table.

WHEN we got down to business, the food was fully as good as the ambiance. My opening Pot de la cuisinere Lyonnais was a luscious pig meat confit with foie gras. Mary’s pot of spring vegetables contained such a variety that she wrote them down: carrots, broad beans, French beans, yellow courgettes, scallions, 2 kinds of baby turnips, leeks, baby artichokes, baby fennel—and all cooked to perfection as though they had been added successively to the pot at exactly the right instant.

WHEN we got down to business, the food was fully as good as the ambiance. My opening Pot de la cuisinere Lyonnais was a luscious pig meat confit with foie gras. Mary’s pot of spring vegetables contained such a variety that she wrote them down: carrots, broad beans, French beans, yellow courgettes, scallions, 2 kinds of baby turnips, leeks, baby artichokes, baby fennel—and all cooked to perfection as though they had been added successively to the pot at exactly the right instant.

Mary’s quenelle et ecrevisses was light, fluffy and delicious, in an exquisite fish-soupy shellfish sauce with a few crayfish tails in their shells, brought to the table bubbling hot in a lidded Creuset dish. My own pigeonneau, served with girolles and tiny potatoes in a rich caramelized gravy, was cooked precisely to the point at which it could be removed from its bones without resorting to power tools—highly unfashionable in an age of blood-rare birds still quivering on the plate.

There was a slightly longer hiatus before our desserts and the waiter stopped to apologize that it would be another five minutes.

“Better correct than fast,” I commented.

“That’s the way we work,” he replied with a smile.

The dishes were well worth waiting for. For Mary there was a perfect soufflé williamine with pear sorbet nested in the middle; and for me a layered assembly of cooked strawberries and rhubarb topped with cream and then rough cubes of shortbread. It was served in a small Parfait jar with rich vanilla ice cream on the side, in the jar’s detached upside-down lid. Obvious once you've thought of it .

After dessert we were invited to have our coffee upstairs in the  lounge. For those restaurants that can afford the space, it’s a good way of turning the tables without rushing the diners. There were big overstuffed leather chairs, with one corner of the room occupied by a joyously boisterous group about to go into an adjoining private dining room. It was well-managed—a noisy party could enjoy themselves at full volume without impinging on the quieter diners below. We saw no signs of anyone being rushed—certainly not ourselves—but as we left we observed that at least a couple of tables appeared to have accommodated three sittings.

lounge. For those restaurants that can afford the space, it’s a good way of turning the tables without rushing the diners. There were big overstuffed leather chairs, with one corner of the room occupied by a joyously boisterous group about to go into an adjoining private dining room. It was well-managed—a noisy party could enjoy themselves at full volume without impinging on the quieter diners below. We saw no signs of anyone being rushed—certainly not ourselves—but as we left we observed that at least a couple of tables appeared to have accommodated three sittings.

A most enjoyable evening: good food, friendly helpful service and excellent logistics. Like D’Chez Eux, they seem to have mastered the art of being whatever sort of restaurant their diners would like them to be. And perhaps by now the maitre d' has had a quiet word with Little Miss Bossy-Boots.

Aux Lyonnais, 32 rue St.-Marc, 2nd, Tel: 01 42 96 65 04 Mº Bourse

Aux Lyonnais, 32 rue St.-Marc, 2nd, Tel: 01 42 96 65 04 Mº Bourse

The total bill including wine came to 127€

©2005 John Whiting

_______________________________________________________________________________________

Although our dining experience was certainly a pleasant one, there is an aspect of Ducasse’s “modernization” that I have broadly hinted at. Those with long memories may recall this fine institution as it was listed in Waverley Root’s Paris Dining Guide of 1969:

The Lyonnais is (1) the best Lyonnais restaurant in Paris; (2) one of the three best bistros in Paris; and (3) one of the dozen best restaurants of any category in Paris. You will understand here why Lyons is considered a gastronomic capital, although all of M. Violet's fellow Lyonnais do not take as many pains as he does to demonstrate it. For instance, rebelling against the insipid taste of artificially bred trout—which is all that ordinarily can be had, since the government forbids selling brook trout commercially—he imports from Guilvinec, in Brittany, the sea trout which can be legally taken in the river mouths during a very short season in the fall.

M.Violet's menu is a model document. It describes exactly the dishes he presents, and from time to time tosses in a bit of extra information. Under the name of that typical Lyonnais dish, hot sausage, you read 'In Lyonnais families, hot sausage is eaten with butter and boiled potatoes'....

One diner old enough to have experienced Aux Lyonnais both ancient and modern was prompted to term Ducasse's “a Disneyland version”. A further documentation of how our changing tastes and expectations are reflected in its history appeared in March of this year in The New York Times:

We first ate at Aux Lyonnais in 1969, when M. Violet was in charge. We were a party of six, all American academics. The other four members of our party ordered steak. M. Violet grumbled "C'est le bifteck—your wives can cook you bifsteck." "But," they answered," it's on the menu. " M. Violet exclaimed "Moi! je suis le menu."

My husband and I ordered a bottle of the ancient Morgon and "something to go with it." We were served a dish of sanglier—the most delicious meal I have ever eaten. After the meal M. Violet turned his back on our companions and vigorously shook my husband's hand and kissed mine.

After that we returned as often as we could, always ordering a bottle of Morgon and "something to go with it." We were never disappointed. We left Paris in 1970 not to return until the fall of 2001. We found Aux Lyonnais—the meal was good, but M. Violet and the magic were gone.

Does anyone know the history of Aux Lyonnais after M. Violet? We understood that in 2001 the restaurant was owned by a consortium of officials/businessmen from Lyon. What is the relationship between Alain Ducasse and this consortium? Does anyone else remember the Aux Lyonnais of 30 years ago and M. Violet, "le menu?"

An extended discussion of French cuisine old and new, with specific reference to Ducasse and Aux Lyonnais, may be found on the food web site eGullet.

Back to the beginning of this review