The Remains of the Day

Bistro 121

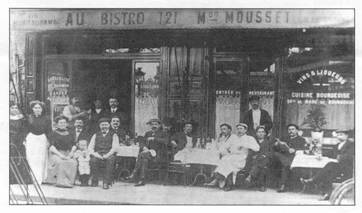

A half-century ago one Monsieur Mousset opened a bistro at 121 rue  de la Convention in Paris’ 15th arrondisement. He called it, appropriately, Bistro 121. An early photo shows a staff of 18 posed outside, some standing, some sitting at tables with generous carafes of wine.

de la Convention in Paris’ 15th arrondisement. He called it, appropriately, Bistro 121. An early photo shows a staff of 18 posed outside, some standing, some sitting at tables with generous carafes of wine.

Seventeen years later Waverley Root wrote it up in his Paris Dining Guide. He gave it four stars, his highest rating, and pronounced it “reasonably priced for its very high quality”. By then the chef was identified as Jean Moussié (certainly not a misprint) and the cuisine was “basically that of the Quercy, but its quality is such that it transcends the restricted merits of regionalism”. How the modern terroirists would fume at such a casual embracing of the eclectic!

When Mary and I visited Paris together for the first time in 1973, a four-year-old guide was as reliable as if it were hot off the press, and so we took Root along as our vademecum. His description of Bistro 121 fitted both our culinary ambitions and our restricted resources. The Quercy meant nothing to us, nor did its territorial wine, Cahors – in those distant days, observed Root, “not too often encountered in Paris”.

There was an intriguing promise of “liévre à la royale, that disappearing triumph of the old school of French cooking”; but it was April, and so we had to content ourselves with more prosaic specialties. I made no notes and have no memories of what we had, only a spreading sense of warm delight culminating in sorbet à l’orange au punch Bernard Blier, accurately described by Root as containing “so much rum that it was practically a frozen grog”.

And there was the Cahors, a splendid provincial wine that has followed me through my life. When I visited the town some fifteen years later I bought, from the local municipal wine shop, the first case of wine I ever purchased. The last of the bottles, still maintaining its virility, was dispatched only a few months ago.

Even Root’s high rating of Bistro 121’s cuisine had not prepared us for its austere modern décor with a grandeur quite at odds with a self-styled bistro. The walls and columns were faced with golden beige mirrors that extended the dining space to infinity. Banquettes around the periphery were luxurious soft brown leather; lighting was by enormous smoky globe chandeliers whose glowing glass was shrouded in plain pale cloth draperies, hanging loosely as though ready to be whisked away at any moment to reveal their mysterious contents.

Even Root’s high rating of Bistro 121’s cuisine had not prepared us for its austere modern décor with a grandeur quite at odds with a self-styled bistro. The walls and columns were faced with golden beige mirrors that extended the dining space to infinity. Banquettes around the periphery were luxurious soft brown leather; lighting was by enormous smoky globe chandeliers whose glowing glass was shrouded in plain pale cloth draperies, hanging loosely as though ready to be whisked away at any moment to reveal their mysterious contents.

The maitre d’ and waiters were as dignified and austere as the décor – woe betide any casual diner who failed to take his meal seriously! That certainly wasn’t us. We went away replete but not gorged, having participated in an age-old French ritual and feeling that the Last Supper could hardly have been more memorable.

-0-

More than three decades later I was looking nostalgically through Root’s Paris restaurant guide and wondering how many of his recommended places might still be open. A quick check on the Internet against the Paris yellow pages immediately turned up half-a-dozen. We were due to return in a few days and I thought of checking them out against Root’s long-ago comments.

First on our list was Bistro 121, freighted with our own happy memories. Zagat rated it “good” on food but “fair” on décor, warning that it was “outdated”. Pudlo called it “emblematic of the 70s” but gave it two knives/forks and identified the patron as Stéphane Mouset, the same family name as the founder in 1952. Promising. Accordingly we reserved for Friday, our last night in town.

It was like stepping through Dr. Who’s tardis into the 1970s. The décor gleamed as fresh as the day the restaurant had opened. The mirrors one would expect to survive undimmed, but even the leather on the banquettes was soft, supple and unblemished. The maitre d’ was handsome, erect, dignified, and as perfectly preserved as the leather. Zagat had warned that the service “favours regulars” and so I told him that we were returning after a thirty-year absence. The revelation actually brought a smile to his lips.

At seven o’clock we were the first to arrive. The carte offered a very reasonable weekend menu at 41,50€ which included half-a-dozen alternatives in each of three courses and a half-bottle of wine. The inevitable Foie gras de canard frais maison was a generous cold slice of a block perfectly poached in Sauternes; the Terrine du moment was a beautifully constructed jellied head cheese with a stripe of paté through the middle and came with a lightly dressed little salad of small mixed lettuce leaves.

Unable to desert the duck, I went on to Filet de canette aux pêches. This was a massive hunk of breast from a very well-endowed duckling, close to an inch thick and crusty on the outside, pink and tender in the middle. The peach sauce was ambrosial and the helping so generous that I willingly shared it with Mary without a shadow of regret. She in turn had chosen Filets de rouget grillés et tapenade d’olives noires and was served four fillets – too many for her, thank heaven! – crisply fried to perfection, the strong simple tapenade a perfect foil for the richly buttered fish. And the potatoes! Small boiled buttered new potatoes with my course, thin crispy fifty-pence-sized sautéed discs with Mary’s. We shared them both out with careful attention.

Our waitress was an attractive Swiss girl working there during the summer holiday – not just another student, but a serious career restaurateuse/hoteliere. Her English was flawless and so it was easy to fall into conversation. How long had the maitre d’ and the chef been with the restaurant? Twenty-two years, both of them. We had noted that as the evening went on there were only seventeen people in a restaurant with a hundred covers, and on a Friday night. How could it survive?

She spoke more confidentially. The patron, she said, intended to close it. The restaurant was solvent, but not returning enough on investment. He had wanted to close in June but had put it off until October. Not being himself the chef, he was lacking the incentive which might have kept it ticking over, and so a fine restaurant with spotless décor, a well-run kitchen and smooth service was about to close its doors after half a century. Thousands of traditional French bistros close every year and Bistro 121 was to become part of the national statistic.

On our way out I shook hands with the maitre d’ and thanked him for having helped to maintain such a high standard of excellence for so many years. He did not appear totally unmoved. If you hurry, you can dine there one last time before all those mirrors are carted off to the dump.

Bistro 121 121 rue de la Convention, 15th, Tel : 01 45 57 52 90, Mº Boucicaut

2008: Wonderful news! John Talbott reports that Bistro 121 is under new management and that the excellence of its cuisine, as well as its ambience, has been preserved. Let's hope that some collapsing bank doesn't undo all the hard work.

Back to the beginning of this review