![]()

Don’t sigh for me,

Bridge of Venice

Four years ago, Francesco da Mosto began the last installment of his four-part televised historical survey of his native Venice with a visit to The Venetian Hotel in Las Vegas, which features an architectural potpourri of the city’s most familiar structures [left]. Unlike the originals today, its false façades are free of advertising. On our recent visit, the Piazza San Marco was monumentally fronted, not with statues by the great Italian sculptors, but with the figures of enormous models wearing the latest creations of Marciano, Sisley and Chopard.

Four years ago, Francesco da Mosto began the last installment of his four-part televised historical survey of his native Venice with a visit to The Venetian Hotel in Las Vegas, which features an architectural potpourri of the city’s most familiar structures [left]. Unlike the originals today, its false façades are free of advertising. On our recent visit, the Piazza San Marco was monumentally fronted, not with statues by the great Italian sculptors, but with the figures of enormous models wearing the latest creations of Marciano, Sisley and Chopard.

“The advertisements in Piazza San Marco are horrible and must reflect badly on the sponsors too,” said Michela Scibilia, a graphic designer who is a member of 40xVenezia, a platform for residents to express their views on urban projects.

But the motive of t his desecration is need, not greed. Funding for renovation projects should come from the Special Laws, said Ms Scibilia. Introduced in 1997, these promised an annual budget of €45m to fund a cycle of crucial urban renovations until 2030. Since 2003, however, the figure has been shrinking; last year just €28.5m was made available. Mara Rumiz, the assessor for public works, says the lack of public funds made it impossible to do such work without recourse to private sponsorship.

his desecration is need, not greed. Funding for renovation projects should come from the Special Laws, said Ms Scibilia. Introduced in 1997, these promised an annual budget of €45m to fund a cycle of crucial urban renovations until 2030. Since 2003, however, the figure has been shrinking; last year just €28.5m was made available. Mara Rumiz, the assessor for public works, says the lack of public funds made it impossible to do such work without recourse to private sponsorship.

So if Venice's tourist destinations are looking more and more like Disneyland, it’s because it must increasingly support them in the same way: namely, by the leasing of franchises and advertising space, together with the income from the sale of bad pizzas, mass-produced masks and tons of glass, an indeterminable proportion of which comes, not from Murano across the lagoon, but from halfway around the world. Our own response to the billboards and the crowds was to frequent the narrow back streets and canals, devoid of souvenir shops, where the tourists rarely intruded.

Though there are some disagreeable things in Venice there is nothing so disagreeable as the visitors.

Henry James

In Venice twenty years ago for an Electric Phoenix concert in the International Festival of Contemporary Music, I arrived at the final solution to the tourist problem. Getting up before daybreak on a Sunday morning, I drove across the bridge from our hotel in Mestre, parked in the Piazzale Roma and walked slowly through San Polo towards the Grand Canal and across the empty bridge. What news on the Rialto? None at this hour!

The streets were deserted; on a Sunday, not even the shopkeepers were about. When I arrived at the Piazza San Marco, it belonged only to the pigeons and the empty chairs.

I ended my perambulations in front of La Fenice, where a small stall was just opening up for early morning coffee. The poster for our concert was over the classical portico [left]. That was in 1985; a decade later the opera house would be destroyed in a fire [right], perhaps set by a couple of electricians who were about to be fined for delays in repair work. Where are they now? Lighting Sig. Berlusconi's all-night orgies? .

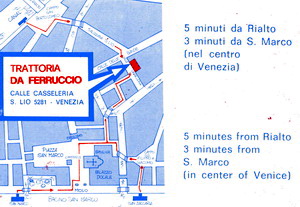

The previous year, on my very first visit to Venice, I was taken by the son of Trento's unofficial coordinator of illegal grappa. We arrived in the early afternoon, just as the good restaurants were closing. We had just about reconciled ourselves to tourist fare of the worst sort, when we came upon an empty but still open establishment on a back street, its cold counter piled high with a cornucopia of seafood. Were they still serving? But certainly, signiori! Benvenuto!

The previous year, on my very first visit to Venice, I was taken by the son of Trento's unofficial coordinator of illegal grappa. We arrived in the early afternoon, just as the good restaurants were closing. We had just about reconciled ourselves to tourist fare of the worst sort, when we came upon an empty but still open establishment on a back street, its cold counter piled high with a cornucopia of seafood. Were they still serving? But certainly, signiori! Benvenuto!

The chef was no longer cooking, but the cordial headwaiter told us that we could have anything we wanted from the cold table. Bring us a selection, we said, whereupon we were served up with enormous platters of shrimp, crab, cold fish salads, oysters—an ocean full of the fruits of the sea. We lingered over them, then asked for more, and yet more again. Two hours later we staggered out of the still empty restaurant, and the smil ing headwaiter locked the door behind us—he had stayed open, without a murmur, for us alone. And the bill had been embarrassingly moderate.

ing headwaiter locked the door behind us—he had stayed open, without a murmur, for us alone. And the bill had been embarrassingly moderate.

Does this place still exist, or has it been absorbed into the mainstream of Venetian tourist traps? I would think it a figment of my imagination, except that the card is before me as I write.