![]()

Siena Preserved

Siena has long been a city of contradictions. In the beginning, its architectural distinction was largely a by-product of solving the all-important problem of distributing water in a city built on hills: for instance, the first major project in developing what was to become its great central square, the Campo, was the building of ditches and channels to improve the drainage in a steep, unmanageable expanse of open pasture.

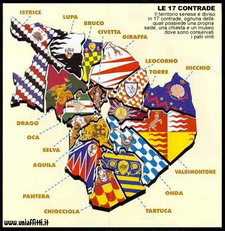

As for its socio-political structure, for hundreds of years it has been fragmented into contrade, which are chartered districts functioning virtually as separate villages. Beginning in the 13th century, the number of them ultimately ran into three digits, but by the 17th century they had merged down to seventeen, which is the total today. Originally they had pragmatic functions such as collecting taxes, maintaining the fountains and providing soldiers, but these have ossified into largely symbolic and ritual activities. Nevertheless, their influence is still profound: you belong inexorably to the one you are born into and each has its own cultural baggage, including church, museum, symbol, colors, fountain and bar/club.

As for its socio-political structure, for hundreds of years it has been fragmented into contrade, which are chartered districts functioning virtually as separate villages. Beginning in the 13th century, the number of them ultimately ran into three digits, but by the 17th century they had merged down to seventeen, which is the total today. Originally they had pragmatic functions such as collecting taxes, maintaining the fountains and providing soldiers, but these have ossified into largely symbolic and ritual activities. Nevertheless, their influence is still profound: you belong inexorably to the one you are born into and each has its own cultural baggage, including church, museum, symbol, colors, fountain and bar/club.

The contrade are in constant daily competition with each other, which is embodied in the great semi-annual Palio, a free-for-all bareback horse race lasting only a minute and a half but followed by a day and a night of ceremonial debauchery. The jockeys are professionals hired in for the occasion; they are so little respected by the locals that for a horse to win it need not even be mounted at the finish line. For days in advance there is so much dealing and double dealing, and the race itself involves such uninhibited violence, that the whole process is probably about as straight as a Kazakhstan election.

With such an ancient tradition of cutthroat competition, you might think that Siena would be the archetypal Berlusconi city. You’d be wrong. For one thing, collective contrade discipline keeps the crime rate very low. Along with Bologna, it is one of Italy’s great left wing strongholds—out of a population of a quarter of a million, some 35,000 voters are card-carrying PDS or Communist Party members, a loyalty partly won by the Communist resistance to fascism during World War II.

Siena owes its architectural integrity and state of preservation to a series of fortunate accidents. After the siege of 1554-5 it declined from banking center to market town. With its treasury no longer awash in ducats, few buildings were built or demolished and open spaces between buildings were devoted to allotments and vineyards, many of which survive to the present day. During World War II, the city was taken without resistance by the French Expeditionary Force [right], thus saving it from destructive bombardment. Today it is more prosperous, but it has wisely preserved its history.

Strolling along Siena’s back streets was like entering a time capsule. I thought of Bologna, and of other unspoiled cities I’d had the good fortune to experience. There were the Berkeley hills with their organic redwood houses that seemed to have sprung directly from the soil. There was Leningrad (St. Petersburg) before the Western capitalists moved in with their ads and neon signs. There was shabby but distinguished Weimar under the Communists. All were historic places which, whether from poverty or principle, had not set about “improving” themselves. So often throughout history, these Siamese twins have proved to be tradition’s greatest benefactors.

As for the politics, the forces that make for preservation don’t appear to  be inexorably allied either to the left or to the right. On the French Riviera, both Cannes and Nice have for well over a century been under the control of their moneyed migrants. Jacques Médecin, Nice’s gourmet mayor for over twenty years, was ultimately convicted of fraud and corruption; and yet the hills above Nice remained remarkably pristine, while those of Cannes were ruined by egotistical architecture run riot. What’s the explanation? Sitting at my computer and looking out my study window at the unsullied sunset over Hampstead Garden Suburb, I am happy to ponder the conundrum.

be inexorably allied either to the left or to the right. On the French Riviera, both Cannes and Nice have for well over a century been under the control of their moneyed migrants. Jacques Médecin, Nice’s gourmet mayor for over twenty years, was ultimately convicted of fraud and corruption; and yet the hills above Nice remained remarkably pristine, while those of Cannes were ruined by egotistical architecture run riot. What’s the explanation? Sitting at my computer and looking out my study window at the unsullied sunset over Hampstead Garden Suburb, I am happy to ponder the conundrum.

©2008 John Whiting