![]()

Merlangius Mersans

or Whiting Immersed

Harstad, Norway, 1998

. . . the fishes

Were of the finest that e’er flounced in nets.

Lord Byron, Don Juan

Thursday, January 29

Here within the Arctic Circle, January is spent waiting for the sun. It was expected to arrive, my driver told me, anytime from about the 18th, but it’s late this year. There’s only a hint of daylight when I come downstairs at eight-thirty: plenty of time for this Whiting to work his way canibalistically through the half-dozen varieties of pickled herring set out for the hotel breakfast. There are herrings in sour cream, herrings in mustard, long delicate pink fillets of sweet-and-sour herring pickled in vinegar and sugar, and little chunks of herring pickled with onions and multi-colored peppercorns that you chew up along with the fish. In case I still feel fishy, there’s caviar, but not the posh kind—this is a spreadable cod’s roe mixed up with oil, salt and sugar. Pretty good—I wouldn’t pay fifty bucks to upgrade it.

Even when the winter sun finally appears you don’t have to arise early to greet it. Its glorious appearance today is the first of the season. Even in England the sun is not so rare as to set the neighborhood gossips a-buzzing; but this morning the gradually rising thin slit of brilliant red on the far horizon, finally skimming over the ice and bouncing off a glittering mass of icicles on a sagging quay-side rope, makes me feel something of the elation that grips these folk after months of lowering cloudage and swirling snowflakes. By late morning most of this morning’s white wisps of cloud have scudded away and there is intense low-angled sunlight all across the snowbanked landscape. I find that I’ve forgotten what a clear pollution-free sky is like. As I look across the bay as if through newly corrected glasses at the distant mountain ranges, I see them with a sharpness and clarity that are breathtaking. If only I’d brought my binoculars! It’s like listening to music after clearing out the earwax, or tasting a delicate sauce after giving up smoking.

And the silence is deafening. There’s so little traffic here on the edge of both town and water (unfrozen even in midwinter because of the Gulf Stream) that even distant footsteps on the loosely-packed snow produce a loud gravely crunch. The sensual pollution I live with every day has become second nature. I must come back in summer when I can stroll about town under the midnight sun, the loudest sounds the rumble of my circulating blood and the humming of my central nervous system.

HARSTAD being one of the principal naval ports at what used to be the cutter-edge of the Soviet sea presence, we’re here on a quasi-military mission. In delayed response to the Viking invasions of northern Britain, we, The Gathering, have brought the carnyx into their very heartland. The carnyx is the wild-boar-headed battlehorn of the ancient Celts, so frightful that its woad-bedaubed exponents were employed to strike terror into the hearts of enemies as far afield as India.

HARSTAD being one of the principal naval ports at what used to be the cutter-edge of the Soviet sea presence, we’re here on a quasi-military mission. In delayed response to the Viking invasions of northern Britain, we, The Gathering, have brought the carnyx into their very heartland. The carnyx is the wild-boar-headed battlehorn of the ancient Celts, so frightful that its woad-bedaubed exponents were employed to strike terror into the hearts of enemies as far afield as India.

But this is a woad-show of a different hue-and-cry, confronting a Norse of a different choler. After two millennia of slumber, this ancient instrument has been re-created by the Three Johns: researched by the Scottish musician-scholar John Purser, reconstructed by metal craftsman John Creed, and brought to glorious life by trombone and sackbut virtuoso John Kenny [left]. (I, a humble Fourth John, am sometimes called upon to multiply the fearsome monster and send its cries echoing electronically around the concert hall.)

The Gathering, which now gathers regularly for such occasions, was formed by John Kenny together with soprano Frances Lynch [right], whose battle-cries can rival those of the carnyx itself. The Scottish early music percussionist Alan Emslie completes the ensemble. We’ve been invited to Harstad for the annual Ilios Festival of New Music. This relatively small town boasts its own Kulturhus with two concert halls, an art gallery, a large public library, and an adjoining hotel. Is the center cost-effective? Enlightened Scandinavians don’t ask such stupid questions.

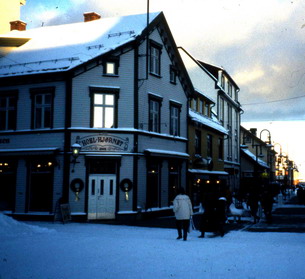

Last night’s dinner at the hotel was acceptable, with a tasty salmon soup and a trio of poached local fish whose flavors survived the anonymous pink sauce which was poured over them. Today I inquire of the guardian angel who has been appointed to watch over us whether there is some other restaurant in town that we should visit. She immediately suggests De 4 Roser [left], a short walk into the center of town. The fact that its bar features the eponymous American whisky is not exactly a recommendation, but in a small town with limited choice it must be given the benefit of the doubt. A reservation is accordingly made for this evening.

Last night’s dinner at the hotel was acceptable, with a tasty salmon soup and a trio of poached local fish whose flavors survived the anonymous pink sauce which was poured over them. Today I inquire of the guardian angel who has been appointed to watch over us whether there is some other restaurant in town that we should visit. She immediately suggests De 4 Roser [left], a short walk into the center of town. The fact that its bar features the eponymous American whisky is not exactly a recommendation, but in a small town with limited choice it must be given the benefit of the doubt. A reservation is accordingly made for this evening.

We are greeted by the stunningly beautiful hostess and part-owner, whose model-like proportions are not exactly a recommendation of the cuisine. She has been told in advance of our adventurous tastes and does not offer us a menu, but informs us that the chef will come out to tell us what we are going to eat. I like that. I have no dietary restrictions, whether based on allergy, aversion or divine revelation: any food, when well-prepared, is acceptable.

Only two of us will be drinking wine, so one bottle will suffice, particularly at Norwegian prices. The list is short, select and very expensive. Our hostess suggests a Pinot Bianco Village 1995 from Coltorenzio in the South Tyrol, an obscure area known locally for its dry whites. It proves to be a good accompaniment to the early courses: a short burst of astringent but not too acid flavor that quickly gets out of the way and lets the delicate fish flavors shine through.

The chef who comes to consult with us is one of two in the open-plan kitchen, each as young and thin as the other. Together with the hostess and her slender young waiter, their collective ages and weights would perhaps add up to a single Lyon chef of either sex. As the food starts to arrive, I can understand their sylph-like figures: first comes a large dish with a triangle of three small fried scampi, together with a tiny scattering of crunchy vegetables. The scampi are supernaturally fresh, almost wriggling on the plate. Better these three than a dozen of the usual limp specimens; I’m reminded of a concert in rural Sweden several years ago in the dead of winter, after which we all ate family-style in the village hall from half-a-dozen huge bowls of freshly-caught shrimp which seemed to leap straight into our mouths until we could hold no more.

Next comes a small chunk of poached monkfish with a white sauce so delicate as to provide little more than lubrication and decoration, accompanied by a tiny dollop of puréed potato so rich and buttery that I could happily send to the kitchen for the bowl and forego the rest of the meal. That would have been a mistake. The springily-textured monkfish is a whole pallet (palate?) of delicate flavors that shimmer together in the mouth like an oral aurora borealis.

Next comes a small piece of poached halibut with another delicately creamy sauce, also a revelation in freshness, followed by a whalemeat steak fried to a crisp brown on the outside and cut diagonally into juicy dark red slices. There is a faint fishiness to the flavor, as with the English beef that used to be fed on fishmeal, and a suggestion of liver; otherwise the rich flavor of well-hung game. This is duplicated in the even richer and gamier undomesticated reindeer steak which follows, together with a small helping of rösti potatoes. The meats are served first with fresh cranberry sauce (a bit sweet for my taste) and then a rich traditional sauce made from red currant jelly, gjetöst (strong brown goat cheese) and sour cream. Delicious!

—Did you say whale?! reindeer?!

—Yup. Tomorrow night I’m going to tuck into their Seared Santa.

Friday January 30

Last night's delicate fish flavors make me very interested in a fish poacher/steamer. Back in London they start at over fifty pounds—that's a lot of money for something that will get used only for certain kinds of recipes. In the meantime, I must shop this morning for something essential, a cheap attaché case to take home some delicate radio mics which will have to be displaced from my suitcase. The first shop I go to offers a plastic case at about thirty pounds. I hate to spend so much on something I'll probably never need again. Let's look a bit further. . .

Just along the street is a kitchen shop with a " SALE" sign in the window. Inside the Arctic Circle, a January sale has got to be something really serious. Sure enough, there's a Norwegian-made stainless steel fish poacher for just over twenty pounds. Let's see. . . The shape will just hold the radio mic components. Now, if I tape it shut and put it in a strong carrier bag, it should be even stronger than a plastic case. Lateral thinking wins again! With luck, my accountant won't be able to read Norwegian and I can put it through as a business expense. Old-fashioned "steam radio", as they used to call the BBC Home Service, could take on a whole new meaning.

NOW FOR something really useful to put in it. In Northern Norway, salt cod is not so much a food as a way of life. In the speciality shop at the airport were a couple of splayed rock-hard codfish hanging over a hook for decoration—certainly not for sale to the squeamish. But I had put my nose close to them and caught a whiff of the strong odor that used to come over the fence from Captain Kemp's backyard, where he'd hang up rows of them to harden into salty slabs that, if they finished him before he finished them, would have passed on to his descendants. Skulijoe, the Portuguese fishermen in Provincetown used to call it. We called it fisherman's candy, and Captain Kemp would sometimes give me a piece to suck on until my mouth was as briny and puckered as the cod itself. God's gift to the beer drinker! If the Methodist parsonage had housed a secret cask, I could have guzzled my way into the Guinness Book of Records!

my nose close to them and caught a whiff of the strong odor that used to come over the fence from Captain Kemp's backyard, where he'd hang up rows of them to harden into salty slabs that, if they finished him before he finished them, would have passed on to his descendants. Skulijoe, the Portuguese fishermen in Provincetown used to call it. We called it fisherman's candy, and Captain Kemp would sometimes give me a piece to suck on until my mouth was as briny and puckered as the cod itself. God's gift to the beer drinker! If the Methodist parsonage had housed a secret cask, I could have guzzled my way into the Guinness Book of Records!

On the edge of the harbor is a fiskematbutikk—a fish shop where you can buy not only whole or filleted fresh fish but also minced fish of the finest quality for making your own fish balls and puddings, or even the end products themselves for a peripatetic feast. I would gladly yield to that delicious temptation, but I'm saving myself for a return visit to De 4 Rosen.

Norway is one of the prime sources of salt cod and this is one of the principal harbors from which it can still be caught in relatively unpolluted waters. It can be prepared in a number of different ways: "ketch salting", in which layers of fish are alternated with layers of salt; "pickle salting", in which the cod is packed with salt into crocks, and heavily or lightly salted versions of both, with infinite gradations in between. The more lightly salted, wetter versions must be kept refrigerated, but the rock-hard skulijoe I grew up with will still be hanging around to swing in the last blast from Gabriel's horn.

The stocky apron-clad fish merchant who serves me speaks English more comprehensible than that of Billingsgate, so I'm able to tell him I want salt cod you could kill a man with at ten paces. He goes straight to it—hard gray slabs streaked with white like Norwegian floorboards. The cost is about half of what I pay in Britain for soft salt cod with a high water content, so I come away with about three pounds for less than ten quid. I can safely pack it into my suitcase, giving my clothes a gentle whiff of clam flats at low tide.

Back home I'll make up a lifetime supply of brandade de morue, which is the Provençal method of making the flavor of raw garlic appear subtle. Well-soaked salt cod is lightly simmered and then combined—boned but not skinned—with warm olive oil and milk and all the spare garlic you have lying around. Sissies, i.e. Parisians, subdue it by adding mashed potatoes. In fact, it takes a lot of potato even to begin to mask the strong, penetrating flavors. I put it undiluted in a square container in the fridge, where it solidifies into rubbery fish glue which can be sliced into portions and frozen in plastic bags. A minute or two in the microwave restores its original texture, whereupon it can be mixed to taste with mashed potato and some more olive oil. It only takes a spoonful to give a big dish of mashed potatoes a noticeable souvenir de mer.

NEXT I must find some black leather fur-lined gloves. I’ve lost one of a pair, and what better country to replace them in than here in Norway, where they know that a man’s well-being can depend on keeping his pinkies unfrozen? The most elegant men’s store in town is also having a sale, with the result that they’re out of sizes appropriate to anything but mice or elephants. Just around the corner is another clothing store, this one aimed at the other end of the market. Their bizzarely decorated coats and leggings must have been left behind by extraterrestrials—Clothes on Counters of the Worst Kind. My unhopeful inquiry brings from under the counter a tray of perfectly presentable leather gloves, tucked away out of sight as if they were ashamed of them. I find just what I’m looking for in black pigskin, with a white nylon imitation fur lining, which will do very nicely. Only ten pounds; they’d be double that back in London.

Finally, a quick stop at a grocery store. I must take home some gjetöst. (If you can't pronounce that, you may call it gudbrandsdalsost.) It's a cheese made by boiling the leftover whey of goat's milk until the lactose caramelises, which gives it its color. The taste resembles a slightly sweet-and-sour caramel with a smooth texture similar to fudge. It comes in a large block gaily decorated around the edge with prancing little mountain goats. You take thin brown shavings off the top with a special cheese knife and they curl neatly upward, looking unappetizingly like slices of kiddies’ Plasticene.

The cheese section is immediately adjacent to the pickled herrings—they must have seen me coming—so I come away laden with bottles, as well as a plastic bag of salami scraps at a bargain price. Those frugal Norwegians! They’re not going to disdain perfectly good food just because it comes in odd shapes and sizes.

I set out a couple of hours ago in brilliant sunshine, but when I come out of the store I’m facing into a blizzard. I tie my scarf firmly under my chin, zip my North Face Gore-Tex coat up to the neck, pull my Romanian astrakhan hat down over my ears, don my new suddenly-essential gloves and set out bravely into the teeth of the gale. Visibility is so limited that I have to keep re-navigating my course, making certain that I am not wandering off to the left into the hills to die of exposure, or plunging to the right straight into the icy harbor. Half-way back to the hotel a cheerful crowd of teen-agers looms out of the swirling snow. None of them are wearing hats or gloves and a couple haven’t even bothered to fasten their coats. All over the world, ever since Clark Gable removed his shirt in 1934, revealing that he wasn’t wearing an undershirt, all sorts of protective clothing have gradually become—to coin a phrase—uncool. Anything more than a track suit is practically Dickensian.

IN ORDER to allow Frances Lynch to fly out tonight for a show in Sweden tomorrow, The Gathering has been scheduled for a five o'clock performance. The Kulturhuset audience are superb. Who started the canard that Scandinavians have no sense of humor? Certainly not the anonymous authors of the old Icelandic sagas, who howled themselves silly over the latest bout of decapitations. The theme of the festival is Humor in Music, and the audience need no prompting to laugh at Frances' hilarious interpretation of all the characters in King Harald's Saga, or at John Kenny's noisy struggles with a gradually decomposing trombone. The year's first sunshine has entered all our souls.

IN ORDER to allow Frances Lynch to fly out tonight for a show in Sweden tomorrow, The Gathering has been scheduled for a five o'clock performance. The Kulturhuset audience are superb. Who started the canard that Scandinavians have no sense of humor? Certainly not the anonymous authors of the old Icelandic sagas, who howled themselves silly over the latest bout of decapitations. The theme of the festival is Humor in Music, and the audience need no prompting to laugh at Frances' hilarious interpretation of all the characters in King Harald's Saga, or at John Kenny's noisy struggles with a gradually decomposing trombone. The year's first sunshine has entered all our souls.

I owe Frances a debt of gratitude. Her early departure allows me to meet an even more important deadline—an eight o'clock return engagement at De 4 Rosen. Alan decided at the last minute not to join us last night, but our collective enthusiasm has convinced him that he had made a mistake. Tonight I get to play Virgil to his Dante, leading him down into the sub-aqueous delights of the Arctic Ocean.

The other young chef comes out to tell us what awaits our pleasure, followed by our hostess with the wine list. Alan is a serious wine-drinker, so we immediately decide on a bottle of white (last night's successful Pinot Blanc) to be followed by a red. Our hostess' highest recommendation to accompany the reindeer (Santa's off the menu tonight) is a '91 Gevrey-Chambertin from the gifted young Alain Burguet. It's a dicey year—was it harvested pre- or post-hailstorm?—but we've had no cause to distrust her advice. As for the price, it's best forgotten.

The first course is edible art of the highest order: a large paper-thin slice of raw salmon, deeply pink, surrounded by a perfect halo of delicate pale green basil vinaigrette. The salmon is so pure and fresh as to make us realize that part of the flavor we're accustomed to is that of fish fed a questionable diet and just starting to go off. Norway is not particularly noted for its elaborate haute cuisine for much the same reason that Burgundy is not famous for its Gluwein.

If the salmon is sensational, the cod to follow is equally remarkable. It's skrie, mature cod come home to reproduce. Alan Davidson, in North Atlantic Seafood, describes the long careful process of its preparation, culminating in a short fast boil. The end product is a flaky morsel of virginal whiteness and pure flavor, in this case lightly anointed with a thick red wine sauce and accompanied by a small spoonful of simple sautéed potatoes. We savor it flake by flake, certain that we shall never again taste cod of such perfection. My memories of Cape Cod don't even come close.

Monkfish again for our next course, but this time lightly fried and maintaining its resilient bouncy texture. One can see how, in the far-off days when it was cheap, unscrupulous restaurateurs could pass it off as lobster tail, particularly in a bisque or thermador. It's dressed with a sauce vierge, with tiny slices of green beans and pimiento.

Besides our small table for two, our dining room contains a large oval table set for a party of a dozen, who arrive during our second course. Our hostess comes over and says that three of the party would like to smoke. Would we mind? Yes we would, is our equally straight response. The air remains clean and, when we leave, the party calls out a cordial goodbye—no trace of resentment at our veto.

Like the tinkle of sleigh-bells, the Gevrey-Chambertin arrives just before the reindeer. For those accustomed to bold, aggressive New World cabernets, its gentle pinot noir is not attention-grabbing. Wait for the food, we decide. It needs company. The reindeer is served, a fried sliced steak as last night, with the same goat-cheese sauce, but this time accompanied by small baked potatoes and Brussels sprouts prepared much as Alice Waters suggests in her Chez Panisse Vegetables: the leaves separated and sautéed with fat—in this case small bits of bacon—and finished with just enough stock and/or wine added to evaporate by the time they’re done. Mary and I sometimes do them like this at home since we got the book, and it’s reassuring to have them taste so similar coming from a skilled kitchen.

True to expectation, the wine has opened up with the food and has begun to justify our extravagance. By this time John Kenny has arrived for a pot of tea while we polish it off. There being no more room at our little table, the hostess suggests that we go upstairs to the bar. This proves to be two good-sized rooms on the top floor of the building which the restaurant occupies. I’ve been so taken with the food that I’ve not even mentioned the decor, which is that of a prosperous but comfortable old Norwegian town house. Up here, it’s even more like being at home. A leather couch and two armchairs surround a low coffee table.

There’s a party in the next room, but here we are alone. We sit and talk for an hour or so, during which two sampler plates of desserts arrive: a bit of cheesecake, rich chocolate cake, a few stewed cloudberries with cream, a tiny dollop of kiwi sorbet, refreshingly tart. John’s tea is long in coming and the waitress apologizes that they can’t find the particular black tea he wanted, so she must go out and get some more. When the bill arrives at the end of the night, the tea has been left off it. “You had to wait so long we couldn’t charge you.”

REGRETFULLY we toddle off to bed and I have my recurrent dream of an addictive secret substance which makes everything taste delicious. As William Burroughs observed in The Naked Lunch, the aim of capitalism is to sell the buyer to the product. When it’s nectar and ambrosia of such exquisite seductiveness as I’ve enjoyed in Halstad, I’m a willing junky.

REGRETFULLY we toddle off to bed and I have my recurrent dream of an addictive secret substance which makes everything taste delicious. As William Burroughs observed in The Naked Lunch, the aim of capitalism is to sell the buyer to the product. When it’s nectar and ambrosia of such exquisite seductiveness as I’ve enjoyed in Halstad, I’m a willing junky.

©1998 John Whiting