![]()

Two francs for the milk

or

Through Switzerland with open wallet

7 September 1996 Aarau, Switzerland

Yesterday I was the hero of a mini Greek tragedy, though with a happy ending. The dreaded carnet, Customs and Excise's instrument of torture at every European border, is no more, but the hubris with which I arrived at the Swiss border was instantly punished by the official who took one look inside my van and announced that I could not bring in my sound equipment without proper papers. In my previous experience, Switzerland had grown easy-going at its borders, but it does not belong to the Common Market. The fact that I was to be performing for the Association of Swiss Musicians meant nothing to him; that was mere culture, not money. I was escorted to the office of the customs official on duty who, without even looking at the gear, informed me that I must make a list of everything I was carrying—a task as daunting as re-cataloging the Library of Congress—and pay 650 Swiss francs as a deposit against their exportation. No other currency would do, no checks, no credit cards—only God’s Own Money.

Yesterday I was the hero of a mini Greek tragedy, though with a happy ending. The dreaded carnet, Customs and Excise's instrument of torture at every European border, is no more, but the hubris with which I arrived at the Swiss border was instantly punished by the official who took one look inside my van and announced that I could not bring in my sound equipment without proper papers. In my previous experience, Switzerland had grown easy-going at its borders, but it does not belong to the Common Market. The fact that I was to be performing for the Association of Swiss Musicians meant nothing to him; that was mere culture, not money. I was escorted to the office of the customs official on duty who, without even looking at the gear, informed me that I must make a list of everything I was carrying—a task as daunting as re-cataloging the Library of Congress—and pay 650 Swiss francs as a deposit against their exportation. No other currency would do, no checks, no credit cards—only God’s Own Money.

I had two telephone numbers to contact. (A handful of Swiss change that Charles Shere—bless him!—had left with us in London made this possible.) First I called the Swiss Musicians’ office in Lucerne. No answer. The other number was, or rather was not, that of the technical supervisor for the concert series in Aarau. I had phoned him before from London and had twice reached the same patient young woman who told me she had never heard of him. In desperation, my options running out, I phoned her again. Sensing the desperation in my voice, she offered to look him up in the local directory. Miraculously, he was listed. Even more miraculously, he was at home. In a few moments he had arranged for a friend in Basel to bring the money to the border. The whole episode—which, like one’s last moments before a firing squad, had seemed an eternity—had lasted barely an hour.

All this was a valuable update on European politics. I subsequently learned that the free-and-easy attitude I had once experienced at the Swiss borders had evaporated when the Swiss voted not to join Europe. Suddenly they were hard-nosed again. My slap on the wrist was not a serious effort to prevent smuggling, but a reminder that I should not presume to enter without papers. This being Switzerland, money was not only the medium of exchange but also the means of communication. Once he had made his point, the customs official was the soul of politeness, even cordiality. Seeing him again on the way out was like meeting an old friend: the executioner who hadn't been required to pull the lever.

I should have remembered the story that I had been told several years before by a Swiss banker who was helping a friend to organize a concert in Zurich:

Long ago after God had created the world he felt that something was lacking. “I know what it is,” he exclaimed (necessarily to himself). “I will create Switzerland.” So he made the mountains and the valleys and the forests. It was all very beautiful, but somewhat impersonal. “Of course!” he thought, “It needs the Swiss peasant, who will till the soil and keep everything tidy.” But still something was missing from the picture. Who, aside from his silent du tiful wife, would keep him company? “Ah! The Swiss Cow! For Swiss cheese!” And the landscape was complete.

tiful wife, would keep him company? “Ah! The Swiss Cow! For Swiss cheese!” And the landscape was complete.

The rest of the world was not going very well and demanded all of God’s attention. But one day during a brief respite he wondered how Switzerland was getting on. He promptly descended on a cloud to where a peasant was milking a cow.

“Excuse me,” he said, “I am God. I have returned to find out if you like your habitation.”

“Oh yes,” said the peasant. “Every morning when I awaken I thank - I thank Thee in fact - for the wonders with which I am surrounded. The scenery, the fruitful soil, but best of all - the cow! Hast Thou tasted the milk from this wonderful creature?”

“No,” replied God, “as a matter of fact I haven’t. I’ve been much too busy.”

“Then now is the time,” cried the peasant and squirted a generous portion into a tin cup.

God took a sip, smacked his lips and drained the cup to the bottom. “Delicious!” he exclaimed. “Another serendipitous by-product of my creation. Well, I see that I’m not needed here.” And he began to reascend into heaven.

“Just one moment,” called the peasant, extending his palm. “That will be two francs for the milk.”

I once repeated this story to my friend Terry Morgan, who for several years had been a tour guide through Switzerland. “That’s not a joke,” he said, and told me his own sequel:

Every summer Terry took several busloads of tourists around Switzerland. They always made a rest stop in the same small town with a parking space on a side street reserved for tour buses. The punters would alight and empty their bladders and their wallets.

One day there was construction work going on in the usual parking space, so the driver parked across two metered spaces just next to it. While the passengers were trouping from store to store, a shopkeeper came out and demanded of the driver that he put money into the parking meters. The driver, being a gentleman, politely suggested to the shopkeeper that there might be a more appropriate place to put the money. The good burgher withdrew, muttering dire threats.

The passengers returned and the bus got underway. A few kilometres from town a police car, siren howling, overtook them and gestured them to the side of the road. The officer approached the driver with gravity. “Good day,” he said politely. “You owe four francs for the parking meters.”

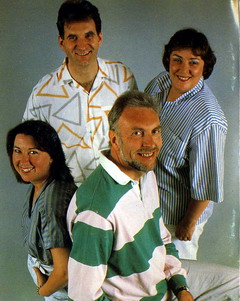

THE SWISS do everything right except when they do everything wrong. The four singers of Electric Phoenix, once they had been delivered to our hotel on the outskirts of Aarau, never heard from our sponsors again before the concert, but were left, as in some television obstacle game, to work out where the concert was, when to rehearse, and how to get there. At least there had been concert programs left for us. Being both experienced and resourceful, they found out what bus to take and where to catch it; Swiss taxi fares might have eaten up the entire fee.

THE SWISS do everything right except when they do everything wrong. The four singers of Electric Phoenix, once they had been delivered to our hotel on the outskirts of Aarau, never heard from our sponsors again before the concert, but were left, as in some television obstacle game, to work out where the concert was, when to rehearse, and how to get there. At least there had been concert programs left for us. Being both experienced and resourceful, they found out what bus to take and where to catch it; Swiss taxi fares might have eaten up the entire fee.

They also had to be adaptable. When they arrived at our prearranged rehearsal time, they found me a couple of hours behind schedule, thanks to the fact that the helper who was supposed to meet me never showed up and I had to unload and set up the whole system unassisted. They helped with what they were able and went away for lunch, during which time I discovered that part of the gear didn’t work because of the lower Swiss voltage. While I was trying not to sweat into the equipment, a Swiss traffic cop noticed that the hall authorities had forgotten to give me the necessary parking permit and left me a one-hundred-and-fifty-franc admonition. I would have preferred a two-franc bill for a cup of milk. Later a Swiss friend of Phoenix with clout took the ticket to the hall manager and told him that, since I wasn’t warned, I shouldn’t have to pay.

We performed to a large audience—by English contemporary music standards, enormous—who vocally demanded an encore. Half the program was from Trevor Wishart’s Vox Cycle, a vocal obstacle course of such fearsome complexity that most of it has only been performed by Electric Phoenix, for whom it was written. To learn it demands that four virtuosi settle down like a string quartet for an eternity of unpaid rehearsals. Vox I & II, which include a pre-recorded  tape and a click track, were learned by us during a residence at the

Abbaye de Royaumont [left], a magnificent Cistercian Abbey, now an art center, just north of Paris. We ate in our own little gothic hall, the table groaning with platters of good peasant food and bottles of wine. For a week we took the traditional monastic vows of gluttony, insobriety and indulgence. Rabelais’ Abbey of Thélème was a Victorian work house by comparison.

tape and a click track, were learned by us during a residence at the

Abbaye de Royaumont [left], a magnificent Cistercian Abbey, now an art center, just north of Paris. We ate in our own little gothic hall, the table groaning with platters of good peasant food and bottles of wine. For a week we took the traditional monastic vows of gluttony, insobriety and indulgence. Rabelais’ Abbey of Thélème was a Victorian work house by comparison.

This experiment in rigorous self-denial was so successful that Trevor promptly wrote us Vox 3, this time without a backing tape but of such rhythmic complexity that each singer was given a separate click track from a four-track cassette player. Their feelings were perhaps summed up on another occasion by the Composers’ String Quartet of New York. Eliot Carter’s Third Quartet has two click tracks, one for each half of the ensemble. The first fiddle was asked in an interview if he resented this. “If you were drowning in the middle of the Atlantic,” he replied, “would you object if you were thrown a life raft?”

But back to Switzerland. Alles gut was gut endet, to coin a German proverb. At the end of our concert the Swiss radio producer declared that it was the best sound projection he had heard in the hall. This was largely due to Ambisonics, a surround sound technology which I’ve written about extensively elsewhere and which my friends know better than to bring up in my company. Those who are so rash as to request further information learn more about the subject than they ever wanted to know.

THE SWISS composers who had booked us introduced themselves after the concert and invited us out to dinner. The singers, noting that I’d be lucky if I arrived in time for coffee, had pity and helped me to tear down, pack the flight cases and load the van. We all arrived at the restaurant shortly after the official closing of the kitchen, an irregularity which, although they’d been warned we might be late, resulted in a lengthy consultation as to whether and what they would serve us. They graciously decided on a choice of two main courses. Later the manager, in a convincing impersonation of a fading actor, came to our table, stood at attention, recited “Guten Abend” as if from a teleprompter, and did not stay for an answer.

After dinner I told the Swiss creation story, first citing its impeccable source. The Swiss composers did not laugh, but looked thoughtful. I feared I might have offended them. After dinner our host and I went to the cashier to have my parking ticket validated and I saw that he had to pay for it, in spite of the fact that he had just spent maybe half a thousand Swiss francs for all our dinners. In the lift down to the garage he muttered a belated reposte: “That will be two francs for the parking.”

Certain Swiss hotels and culinary schools are still among the most highly regarded training places in the world, but in the cities the Swiss no longer appear to be very fussy about what they put into their stomachs. Most of the restaurants, large and small, have apparently fired their chefs, thrown away their stoves, and embraced the freezer and the microwave. Almost everything I was served I would gladly have traded for a Burger King Whopper.

Our first dinner was at our neat little hotel on the edge of town, whose rustic restaurant was packed with locals. Ravenous after a long day’s drive with almost no lunch, I chose an expensive pork steak Cordon Bleu, a Wiener Schnitzel tarted up with runny cheese inside the batter. This arrived so dried out and intractable that only a fearsome hunger compelled me to get through it. As if to admit that it wasn’t all it should have been, they brought me an unrequested catsup bottle.

Nevertheless I have been known to enjoy Swiss food very much, especially when it's prepared by foreign chefs. In Zurich, in the century-old Bodega Española, I once waited two hours for a paella which turned out to be the best I’d ever eaten. I insist that my judgement wasn’t clouded by the bottle of Campo Viejo I knocked back while I was waiting.

For those accustomed to the urban jungle, it’s also a pleasure to walk about the city streets well after dark without a bodyguard. The Swiss are very crime-conscious. “Please watch your personal belongings,” says a sign, “and help to prevent the 700 yearly thefts which take place in Zurich airport.” Not by the Swiss, of course; airports are full of foreigners.

They’re also very world-security-conscious. When I was a guest in a luxurious new house several years ago, I marvelled at an enormous safe door. Did my host really have that much money? No, it was a bomb shelter, with preserved food, drinks, and an oxygen tank. Such a feature remained compulsory for all new houses until it was finally admitted that, in the event of a nuclear disaster, the time one would have to spend inside would far exceed the life span of a Methuselah.

They’re also very world-security-conscious. When I was a guest in a luxurious new house several years ago, I marvelled at an enormous safe door. Did my host really have that much money? No, it was a bomb shelter, with preserved food, drinks, and an oxygen tank. Such a feature remained compulsory for all new houses until it was finally admitted that, in the event of a nuclear disaster, the time one would have to spend inside would far exceed the life span of a Methuselah.

Paul Krassner, who used to edit The Realist, insisted that the Swiss had a sense of humor. He was right. One of Zurich’s best-loved literary figures is memorialized by a life-like sculpture huddled on a bench at a bus stop. Krassner’s evidence was less outré but equally convincing. He once stayed in a modern Swiss apartment house which had a garbage disposal chute in every kitchen. He could open the flap and hear the subterranean rumble of the machinery. Bottles dropped in would bounce tumultuously off the metal sides and end with a great crash as the monster devoured them.

Krassner became obsessed with the machine and decided to test it to destruction. When his old Olivetti gave out, he threw it down the chute. There was a sickening crash and the machinery ground to a halt. “Oh my God!” he thought. “I’ve killed it!”

The next morning the machinery was rumbling again and he saw a sign in the lobby which endeared the Swiss to him forever. It read: PLEASE DO NOT OVERLOAD THE GARBAGE DISPOSAL

But the last word goes to the angel from heaven who found me the vital phone number. Once settled in Aarau I called and left a message on her answer phone explaining how indispensable she had been and inviting her to the concert. While I was setting up the gear the next morning, her charming boy friend arrived at the concert hall with a note from her, in flawless English, saying how glad she was to have been able to help and how much she would like to come to the concert (I gathered from conversation with him that they actually liked modern music!) but that it was her mother’s fiftieth birthday party and so she wouldn’t be free. The beautifully written, hand-delivered note was so I would understand why she hadn’t picked up the tickets. It’s an ad hominem argument in favor of the essential Swiss character, but when you’re discussing real people that’s the only kind there is.

Actually, the very last word always goes to money. Back home, as I write this journal in its final form, the Guardian comes through the door with a front-page headline revealing that Swiss banks are still sitting on four billion quid’s worth of Jewish gold melted down by the Nazis, much of it dental. You can bet that it’s been part of their security for massive world investments. The British Foreign Office has been complicit in the cover-up. There’s talk of fitting out Big Ben with a cuckoo clock.

©1996 John Whiting