![]()

If it were a Frank Capra movie, it might open sort of like this:

Old John is reaching his three-quarter-century mark. He’s sitting at his computer, where he spends most of his waking hours. On a whim he does a Google search for his best friend from college days, now a fellow-geezer he hasn’t seen or spoken to since their brief London reunion, maybe two decades ago. His name and phone number pop up on the screen, listed in a small California town. Could it be the same?

[fade out narrator, fade in dialog] In some trepidation, I dial the number. Dial? No, I must be dreaming—no dials now, just buttons. “Hello.” It's the voice of a young man, maybe in his twenties. Must be a wrong number.

“Did you go to the University of California?” I begin querulously. No, that’s wrong—pull yourself together. “I mean, College of the Pacific.” I must sound like a doddering old fool.

“Yes…” from the strong young voice at the other end, now with a note of curiosity.

“Does the name John Whiting mean anything to you?”

“John Whiting? Yes, of course!”

“My God!” I respond in amazement. “So it really is…”

Let's call him Jack. [fade to flashback…]

§

In the eyes of a dutiful preacher’s kid just starting college, Jack was glamorous past emulation. He was confident, articulate, humorous. Along with his gift of easy communication, he was handsome beyond the empty pretty-boy good looks of a matinee idol. There was a shrewd intelligence in his face; his steady eyes seemed to look into my soul—a Greek statue come to life.

We hit it off immediately. He was the only All-American Boy I had ever encountered who wasn’t contemptuous of art and preoccupied with sport; the approval of such a paragon was like being accepted into the American mainstream. Sometimes he would entertain me with a monolog, at others he seemed to be picking my brains like a—not so much a Grecian as a Martian, a shrewd creature from another planet eager to fill the gaps left by a hurried briefing. When he was amused he would throw his head back and laugh like a god, a ringing laugh that never rose to a screech or descended to a guffaw.

Jack had set out to become an actor: anything else would have been a betrayal of his talents. Actors, like writers, are jackdaws, storing away the details of human behavior in compartments from which they can be plucked and assembled into nests from which unique characters may hatch. For Jack, I was not just a friend (and I never took this as any sort of betrayal): apparently I was also a useful source of raw material.

In those days I was a reluctant virgin and Jack’s tales of his sexual encounters filled me with admiration and desire. They did not consist of salacious detail, which I never asked for, but were evocative vignettes, such as driving a tractor across a hot sunny field, seeing a girl reclining against a haystack, stopping and making love without a word, spontaneous as a pair of gazelles in an enchanted forest. (Was every word gospel? No matter—it was poetry.) Violence never entered into these tales; in my late adolescent imagination, sex was always harmless, consensual, without consequence and, in some amorphous way, noble.

§

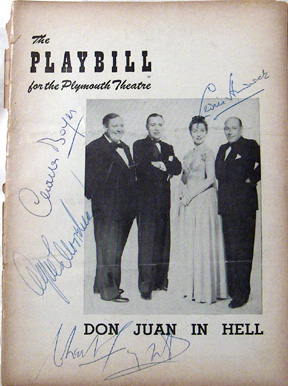

In 1951 Paul Gregory presented The First Drama Quartette in an austere minimalist production of George Bernard Shaw’s Don Juan in Hell, the third act of his Man and Superman. It’s a philosophical debate among Don Juan, the righteously aggrieved Doña Ana, her worldly-wise father Don Gonzalo, and the Devil. The eminent virtuosi reading the lines were Charles Boyer, Agnes Moorehead, Cedric Hardwick and Charles Laughton.

When the production came to town, Jack and I were among the first eager punters at the ticket window. (Along with a couple of student actor friends, we had formed our own drama quartet, asking life’s eternal questions into the unanswering night.) The San Joaquin Valley, home of the world’s worst wine, did not often attract actors of such sophistication, and so throughout the performance I listened as in a dream. With these infinitely wise eminences in formal dress behind their podia, it was like an Oxford Union Debate in heaven.

Charles Laughton, who had conceived and directed the production, was primus inter pares. Jack must have turned on his charm to good effect, for he somehow insinuated himself backstage. Not long afterwards he quietly informed me that he was to become Laughton’s companion.

I knew exactly what that meant—the Hollywood gossip had reached even me, the most naïve of ingénues—but in spite of my straight-laced upbringing I felt, not condemnation or disgust, but a frisson of excitement on Jack’s behalf. Our relationship had never been remotely sexual, so there was no question of jealousy. I already knew something of Laughton’s circle, which included some of the most talented people in Hollywood—indeed, the world! What an Olympus Jack would inhabit! I had read enough Plato to be aware of an age-old tradition in which intellectual initiation and sexual intimacy went hand-in-hand—without sex, our minds as well as our bodies would be much the poorer. And Jack was such a close friend that I knew he would report back to me, the echoes of his adventures reverberating within the narrow walls of my own small world.

There followed half a decade in which Jack brought me dispatches from the Olympian heights. There were eyewitness reports of the pre-Columbian statues surrounding Laughton’s Hollywood swimming pool; dinner parties with such luminaries as Vincent Price and James Thurber, while Orson Welles sat morose and drunken at the far end of the table; and most memorably, a stroll through Frank Lloyd Wright’s Taliesin West, its creator gesturing towards a wall decorated with a few undulating semi-parallel lines and explaining, “It’s a fugue.” What a revelation! I would recall it years later when Ansel Adams confided to me that he had almost become a harpsichordist rather than a photographer.

Jack returned from the filming in England of Hobson’s Choice, bringing me a magnificent Dunhill quarter-bent yachtsman shell briar that Laughton had helped him select. (After I had chewed through several s tems I gave up pipes altogether, but today I could lay my hands on that precious memento in an instant.) Jack was with Laughton in 1954 when he directed—indeed created—Night of the Hunter. This remarkable film was so far ahead of—no, outside of—its time that it was a financial and critical failure. It would one day be acknowledged as a masterpiece, but it was not enough to establish Laughton’s reputation in the vulgar mind as a genius rather than just a funny fat man. Meanwhile Orson Welles, drunk and incoherent at Laughton’s dinner table, would achieve immortality. What differentiated them?

tems I gave up pipes altogether, but today I could lay my hands on that precious memento in an instant.) Jack was with Laughton in 1954 when he directed—indeed created—Night of the Hunter. This remarkable film was so far ahead of—no, outside of—its time that it was a financial and critical failure. It would one day be acknowledged as a masterpiece, but it was not enough to establish Laughton’s reputation in the vulgar mind as a genius rather than just a funny fat man. Meanwhile Orson Welles, drunk and incoherent at Laughton’s dinner table, would achieve immortality. What differentiated them?

My own idiosyncratic explanation is that Laughton’s creative confidence was inexorably tuned to his public. He had a feedback mechanism that took its cue from the audience response, while Welles went brilliantly but blindly onward, measuring his accomplishment against his self-evaluation. He could thus make film after film, often at his own expense, caring little for their critical reception or financial success; while Laughton, devastated by the popular failure of his greatest work, never attempted another ambitious project. He is a classic instance of a great man whose highest achievement depends on a public as generous as himself.

§

Laughton was a story-teller and a teacher, and he loved to have a visible audience in front of him. When his life was unbearably painful—indeed, when was it not?—he devoted himself to public readings whose content was meticulously chosen with the help of a literary advisor whose name I no longer remember. Thomas Wolfe was brought before us, as large as Laughton himself, and Jack Kerouac, long before he was taken seriously by the literary establishment.

Laughton was a story-teller and a teacher, and he loved to have a visible audience in front of him. When his life was unbearably painful—indeed, when was it not?—he devoted himself to public readings whose content was meticulously chosen with the help of a literary advisor whose name I no longer remember. Thomas Wolfe was brought before us, as large as Laughton himself, and Jack Kerouac, long before he was taken seriously by the literary establishment.

Jack had told Laughton of my literary ambitions and enthusiasms and so, after a reading in San Francisco, I was generously invited to join them in Laughton’s hotel room. Sprawled in a huge chair, he looked and sounded utterly drained—what energy he had poured into those readings!—and yet he discoursed for over an hour before saying goodnight. I was so overcome by the sheer weight of his personality (not his body, which had become irrelevant) that I can remember nothing of what he said, but I was left with a lasting sense of what it is like to be in the presence of genius.

What magnanimity! I was nobody, but Charles Laughton had treated me like a person of importance. For me it was the beginning of a conviction, growing through the years, that there are age-old lines of artistic and intellectual continuity, transmitted through a succession of human conduits who make it their purpose to be carriers and custodians. The "Life Force" Shaw called it with his usual high drama. Charles Olson in his essay, Projective Verse, wrote similarly: A poem is energy transferred from where the poet got it…by way of the poem itself to, all the way over to, the reader… Years later I would experience this alchemy while putting together a complex performance tape for Henri Pousseur, working unguided from a few pre-recorded segments and written instructions. I felt as if he were standing just behind me, telling me what to do next. Such moments have given me hope that perhaps my sprawling disjointed life has not been totally fruitless.

That evening with Laughton also taught me the beginnings of a profound respect—a love of being in the presence of someone whose accomplishments far outweigh anything I can ever hope to equal. I have never been competitive and have always loathed sport; when I was researching the entry on “Games” for a cheap serialized encyclopaedia I was delighted to discover an obscure Pacific island that had invented its own version of football in which the object was to end in a tie.

Such an attitude has allowed me to revel in the talents and triumphs of others; as a musician I was, both in principle and practice, a team player. It has also made me contemptuous of gossip-mongering biographers who write smugly of the shortcomings of men far greater than themselves. To such as them, Achilles is all heel. “Admiration,” my Berkeley friend Paul used to say, “is a state of mind no critic can afford to be without.”

§

Last night Jack and I spoke over the phone for an hour, during which we determined that all our mutual friends are now dead. During the whole conversation there was never a hint in his voice that I was listening to an old man. For me it was a great relief, for when we last spoke he was grimly hanging on to a federal job he hated under a boss who made his existence a living hell. It pained me to remember all that beauty, talent and dedication and to see where they had led.

Woody Allen’s lates t film, Match Point, is about luck. Professional tennis, like acting, can reduce a human being to the status of an insect. A ball a couple of inches over the line, a part denied you at a critical stage in your career, and you’re merely a beetle scuttling across the pavement at the precise moment when a foot comes down.

t film, Match Point, is about luck. Professional tennis, like acting, can reduce a human being to the status of an insect. A ball a couple of inches over the line, a part denied you at a critical stage in your career, and you’re merely a beetle scuttling across the pavement at the precise moment when a foot comes down.

But Jack, bless him, is now a decade into happy retirement. He lives in a beautiful town, for the past ten years he’s been with a woman he loves, and his hands are busy with sculpture that sometimes gets exhibited. I’ve told him more than once that he ought to write down what he saw and heard on Mount Olympus, but hell, that’s just me trying to remake him in my own image—he is now a sculptor, not an actor or a writer. He’s blessed with good health, the past is over and done with and he’s living for the present, even the future. Not bad for seventy-six! In another year, will I still be as lucky as Jack?!

©2005 John Whiting

Return to TOP