![]()

ART for art's sake

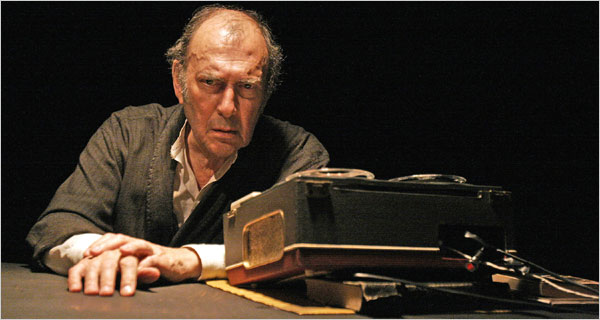

Harold Pinter in Samuel Beckett's Krapp's Last Tape

I wrote the following in 1998:

Half a century ago my college education began with a remarkable man named Irving Goleman. Professor Goleman was a sad, hollow-eyed Jew who carried the world on his stooped shoulders. He had been to the edge of the abyss and stared down into it. What he saw was so horrifying, but at the same time so avoidable, that he was driven to impart his vision to his students—even from the occasional depths of depression, in which he had been known to lie on his back atop his desk, delivering his lecture from this funereal position.

He seemed to care for nothing except knowledge and the sharing of it—there was never time enough to impart it all. He organized all of human creativity along great temporal arcs on the blackboard, in which civilizations began in primitive simplicity, ascended towards classical rationality, and then declined into romantic decadence. Everything seemed to fit into these schemes, whether they were applied to ancient Greece, western Europe, or the cultural history of China or India. Like the massive cyclical structures of Spengler and Toynbee, they provided an assurance of order, a guarantee that we were living in a rational if indifferent universe. Apparently this was not enough; years later I would learn that in 1960 my beloved mentor had committed suicide A former student who became a professor at the same college wrote a generous appreciation.

PROFESSOR Goleman had an acquaintance whom he declared to be even more brilliant. After effortlessly taking a PhD in philosophy, this intellectual paragon set about writing down everything he had learned. Known languages—of which he had mastered several, both ancient and modern—proved insufficient for the task, and so he invented his own, encoded in a three-line notation consisting of a tripartite staff of cursive oriental-looking scripts. I used to have a tiny scrap of it, in which a thick line, as of upper-case letters, was paralleled above and below with narrower, more dense lines, resulting in a complex multi-layered calligraphy.

The learned scholar turned out reams of this tantalizing script. All day and all night he did nothing except eat, sleep, write and relieve himself in a corner of his padded cell. Solitary confinement had become necessary after he realized that he was God; thenceforth anyone who disagreed with him over the slightest thing was declared anathema and sentenced to summary execution. His few visitors communicated with him from a respectful distance.

Both these formidable intellects had dedicated themselves to the revelation, preservation and propagation of truth. They seemed to have no ulterior motive, other than a certain power-pleasure which comes in a more widely destructive form to those who seize control over others through politics, finance or warfare. For these two noble minds, fulfillment lay in the hope that their insights would be conveyed to posterity. In a word—they were artists.

ONLY within the last two centuries of Western civilization have successful artists been able to exercise such single-minded intransigence. Beethoven was the first to successfully thumb his nose at patron and public alike, diving deep within his psyche in search of insights which went beyond the conventional and the reassuring. Through his efforts the artist partially regained his prehistoric status as a sacred madman. This was carried even further by Schumann and the Davidsbündler with their Bacchic abandon, poking fun at the Philistines who kept the engine of society ticking over. When rejection and poverty resulted, these liabilities became romantic assets in the hands of Murger and Puccini.

Such eccentricity was allowed and even celebrated because the respectable burghers, like the mediaeval lords before them, felt themselves to be part of a human community in which their appointed representatives, whether priests or jesters (or artists, who played both roles) could safely be delegated to carry out certain ritual activities on their behalf, such as praying and playing. Those so favored gradually amassed great power: the church, the universities, and finally the art dealers, those arbiters of taste who persuade wealthy patrons that their money can most profitably be invested in the monumental works of art which were commissioned by their predecessors for the purpose of self-glorification.

IN THE course of the twentieth century, a consensus evolved in the West that members of the growing middle classes had a right to economic security in the form of stable employment. This gradually became the norm: either by law—as in education, the civil service, and certain categories of unionized employment—or by custom, as in securely established businesses that enjoyed the efficiency, together with the modest but reliable return on investment, which such stability made possible. (Eventually such quietly-ticking-over firms would become prime targets for take-overs and asset stripping.)

Artists also benefited from this mood of economic benevolence. Throughout post-war Europe, Arts Councils were set up which gave money to institutions and individuals that they deemed worthy of support. These were invariably artists whose work was not already self-perpetuating—why give to those who did not need it?

In order to justify such largess, many artists felt that the magnitude of their work must be commensurate with the generosity of their patrons. Their paintings became enormous and enigmatic, their language obscure, their musical structures massive and impenetrable. The end products were critically evaluated, not by the pleasure or enlightenment they gave, but by their scale and the collective effort which went into creating and then unraveling their mysteries.

But during the past two decades, Social Darwinism has made a comeback. Economic security has been swept away and the populist attitude towards the avant-garde has changed from deference or amusement to contempt. Artists no longer know where they stand. Should they address an audience whose percepions have been dulled by years of mind-numbing television commercials? Should they paint in the manner of those graphic designers who stole their attention-grabbing techniques from the very avant-garde which is now discredited? Should they reduce their music to the hypnotic patterns of the tuneless chant and the drum machine?

The conflict is made even more acute by the rise of business sponsorship. Arts Council funds are increasingly "topped up" by contributions from industries which, although paying only a fraction of the total costs, claim the right to up-front acknowledgement, often taking first billing over the artists they are supposedly promoting. The public, mistaking the froth for the beer, becomes convinced that state support is being replaced by private sponsorship and is no longer necessary. (Acknowledging their new insurance sponsors as well as the Windsor family, the Shakespeare Company is now doubly Royal.)

THE modern insulation of the artist from public opinion has been a mixed blessing. From one standpoint, the gothic cathedrals were one of the greatest con-tricks ever foisted on a gullible populace. Convinced that they were laying up treasures in heaven, patrons allowed their wealth and craftsmen their work to be exploited for the greater glory of the clergy. But the result was a unified community in which a wide range of economic classes felt a strong identification with the product, both physical and social, of their corporate labors.

In these skeptical times, can the cast-off human remnants of the auto industry in Detroit look at the deserted factories and feel any pride at having helped to put them there? Do these ruins show any sign of the loving attention which led mediaeval stonemasons to lavish hours of work on figures in obscure places where they would ultimately be seen only by God?

ARTISTS today must make their most important decisions unaided by convention or tradition. Stretching between open simplicity and dense obscurity is a continuum along which they may at any point choose to stake out a claim. When they must invent their own traditions as they go along, they are less likely to respond to each other's work, and so arguments among them are often about the sources of their funding rather than about form or content. The resulting debate is more often political and economic than aesthetic.

And no wonder. There's lots of scope for cynicism when the Rolling Stones are Windows dressing and Bob Dylan hires himself out to entertain the Nomura Asset Capital Corporation. There's no question of Wall Street having been radicalized; says Nomura's president Ethan Penne, "I am not here paying someone a lot of money to amuse themselves—they are here to amuse me."

At the other end of the scale – the Beethoven end – there's Stockhausen, who has not only (like Wagner) been able to build an auditorium in Japan to the specifications of his own music, but has utilized the services of four helicopters to transport the Arditti Quartet into spatial realms which leave those high-flyers, the Kronos Quartet, relatively earthbound. But not for long. A sponsor is bound to appear who will be prepared to blast them into outer space, where they can spin out recycled Glass for all eternity.

Lost somewhere in the middle of this conflict are the ordinary music-lovers—those who still search for new musical experiences, whether re-interpretations of the music they know and love or expansions of their horizons into new territory whose vistas are unfamiliar but still visible to the naked eye. Such people cannot compete numerically with the millions who are driven to search for multiplicity in tenors or madness in piano-pounders, but the advent of the CD has given them the potential of world-wide unification. The audience for new music has, in fact, shown itself to be receptive to those imaginative entrepreneurs such as the producers of The Unknown Public who go directly to their audience, thus circumventing the barrier of the manufacturer/distributor/record shop as if it were a locked gate in the middle of an open field.

But on a mass scale, those who control our technology control our communication. Greedy manufacturers, sighting the addictive potential of multimedia recording, are already rubbing their hands in glee at the demise of the CD—entertainment for the blind!—and revving up the assembly lines for new works of quasi-art whose conception will run into five-figure costs before a single camera is turned on. The result will be shop-worn merchandise which has been dusted off, repackaged, and given a new price tag.

©1998 John Whiting

The first thing that struck me from our vantage point in the slips directly over the orchestra and stage was that the balance was perfect and the detail crystal clear—it was like chamber music. When the performers are less than perfect, such exposure can be cruel, but this was an integrated ensemble of musicians both modest in their interpretation and expert in its execution. Passions were not torn to tatters, but expressed with an apparent sincerity that swept away all resistance—my suspension of disbelief has never been more willing.

But it was not just the excellence of the performance itself. Art has become so commercial in its motives and methodology that most of it smells of the tabloid rag and the TV commercial. To experience art-driven emotions that are honest and unassuming is to be reminded of how rare they have become: I wept not only for the passing of the heroine, but also of the art that had given her such vivid reality.

IN THE optimism that pervaded the Western world in the second half of the twentieth century, science and economics promised us an upward evolution of continual progress. As the world appeared to improve by leaps and bounds, art lost much of its old appeal and became a stimulating intellectual exercise or mere entertainment. Our environment had been made subject to manipulation just like the inner world of the imagination, thus giving rise to a multi-layered optimism.

But in the new millennium, environmental and social destruction have led to a downward spiral with consequences much more dire than mere romantic decadence. And this time they are not confined to a segment of the earth’s surface but are totally global: there is no vigorous tribe waiting in the wings to ring up the curtain and reenact the drama.

For me, the result has been a return to art as unashamed escape. Through the centuries there have been creative intellects who were able to imagine and give substance to worlds of great complexity, humility, generosity and humor. Art which was deliberately ugly is thought to serve the useful purpose of calling attention to society’s shortcomings, but such reminders are now both superfluous and ineffectual. I seek beauty and nobility wherever I can find it. Confined to a comfortable cell with decent food and wine, an acceptable sound system and the complete works of Johann Sebastian Bach, I could live out the rest of my days in grateful oblivion.

I would also welcome a long conversation with Professor Goleman. In his notes to Wilderness Dave Brubeck wrote:

I am not affiliated with any church. Three Jewish teachers have been a great influence on my life—Irving Goleman, Darius Milhaud, and Jesus. I am a product of Judaic-Christian thinking. Without the complications of theological doctrine I wanted to understand what I had inherited in this world—both problems and answers—from that cultural heritage.

Return to TOP

Return to DIATRIBES INDEX