Bofinger

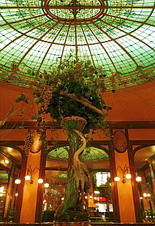

tory behind it. From its opening in 1864, it was the first place in Paris to serve draught beer, whose continually flowing suds lubricated its early success. In 1919 it was expanded into the adjacent buildings, and the present design, dominated by the sweeping curved staircase and the florally ornamented stained-glass dome, was jointly created by the architect Legay and the interior designer Mitdgen. It went from strength to strength and in 1925 was declared by chef des chefs Curnonsky to be “one of the best brasseries in Paris”. It went off form after W.W.II but was bought in 1982 by a consortium who restored the gloss both to its interior and to its cuisine.

tory behind it. From its opening in 1864, it was the first place in Paris to serve draught beer, whose continually flowing suds lubricated its early success. In 1919 it was expanded into the adjacent buildings, and the present design, dominated by the sweeping curved staircase and the florally ornamented stained-glass dome, was jointly created by the architect Legay and the interior designer Mitdgen. It went from strength to strength and in 1925 was declared by chef des chefs Curnonsky to be “one of the best brasseries in Paris”. It went off form after W.W.II but was bought in 1982 by a consortium who restored the gloss both to its interior and to its cuisine. With its enormous daily turnover, Bofinger is the place to go for raw or minimally cooked  seafood. It is as though an inlet from the sea flowed straight through its kitchen. When I was first taken there a few years ago by my old friend and associate David Robertson, the newly-appointed musical director of Ensemble Intercontemporain, we shared a plateau de fruits de mer which quivered with shellfish so fresh that they thought they were still tucked away on the seabed. On a later visit I had a simple boiled crab (perplexingly identified in the menu as torteau, not to be confused with tortue, or tortoise) so sensational as to set it qualitatively apart from the scores I had eaten on both sides of the Atlantic.

seafood. It is as though an inlet from the sea flowed straight through its kitchen. When I was first taken there a few years ago by my old friend and associate David Robertson, the newly-appointed musical director of Ensemble Intercontemporain, we shared a plateau de fruits de mer which quivered with shellfish so fresh that they thought they were still tucked away on the seabed. On a later visit I had a simple boiled crab (perplexingly identified in the menu as torteau, not to be confused with tortue, or tortoise) so sensational as to set it qualitatively apart from the scores I had eaten on both sides of the Atlantic.

On a later  visit with Mary, one glimpse of Bofinger’s fine glass-domed art nouveau interior and its ample seafood menu were enough to persuade her that Bofinger was the place to go for lunch. (Also, not inconsiderable in a wilting heat wave, was its air-conditioning.) It also reminded her of our Vienna favorite, the wonderful Cafe Landmann. Dating from a similar era, Bofinger has been painstakingly restored to all its former glory; but unlike Landmann, the kitchen has been amply staffed and equipped to do justice to the ambiance.

visit with Mary, one glimpse of Bofinger’s fine glass-domed art nouveau interior and its ample seafood menu were enough to persuade her that Bofinger was the place to go for lunch. (Also, not inconsiderable in a wilting heat wave, was its air-conditioning.) It also reminded her of our Vienna favorite, the wonderful Cafe Landmann. Dating from a similar era, Bofinger has been painstakingly restored to all its former glory; but unlike Landmann, the kitchen has been amply staffed and equipped to do justice to the ambiance.

Not having specified the main dining area when we made our reservation, we were escorted to the upstairs dining room, somewhat dark and somber in decor and rather noticeably hotter. But I enjoyed the murals, which are a part of the room’s redecoration in 1930 by Jean-Jaques Waltz, familiarly known as Hansi. Portraying typical Alsatian rural scenes, they are a reminder of the brasserie’s dominant cuisine, which, together with the shellfish, is the charcouterie of Alsace. Besides, it’s always a pleasure to sit in a room which no one has seen fit to modernize since before I was born.

I opted for another crab, preceded by a half-dozen large fine de claires oysters. “They say oysters are a cruel meat,” wrote Swift, “because we eat them alive; then they are an uncharitable meat because we leave nothing to the poor; and they are an ungodly meat, because we never say grace.” If he was right, then I am damned on all three counts. These were sweet and enormous, and I wolfed my way through them as though the ice platter were about to be whipped away for the next diner.

When the crab arrived, its body proved to be more densely packed with moist tasty meat than any I’d encountered, but the claws are disappointingly dry and the points did not come easily out of the shell. It’s a reminder that, when you rely on natural ingredients served with a minimum of preparation, you are at the mercy of nature. Unlike a multi-stage recipe, you can’t add flavorings to dull flesh or inject fluid into dry claws. Even the most reliable sources will occasionally yield disappointment; ordering a crab or a lobster is an act of faith.

After the rich crab, a cold, sharply acidic sorbet de cassis was both cooling and cleansing. Then a demitasse of coffee, a visit to the monumental WC and back into the oppressive heat.

Bofinger 5-7, rue de la Bastille, 4th, Tel: 01 42 72 87 82, Mº Bastille

Back to the beginning of this review