![]()

Cleansing the Palate

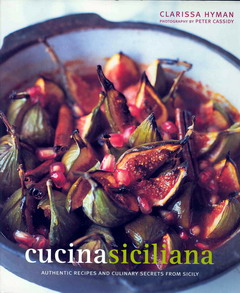

In order to be saleable, a modern cookery book must be beautiful. If a conscientious author is writing about the cuisine of a poor country, there is likely to be a sharp contrast between what is conveyed by the prose and by the pictures. Clarissa Hyman, in the introduction to her prize-winning Cucina Siciliana, speaks frankly of the country’s grinding poverty. She writes of …the intrusive tower blocks…eyesore, illegal buildings…brutally cited power stations… incompleted houses littering the landscape… But you will search in vain for pictures to illustrate such prose; there are only sweeping vistas, overflowing markets, happy peasants, luscious pastas smothered in freshly grated parmesan.

Hyman is equally frank about the people and the society: Superstition and religion go hand in hand… Many are happy to have Mafia chiefs living in their neighborhood – a way of deterring trouble…

The irrational and the threatening inevitably leave their mark on the cuisine: Sicilian cooking is living history, its gastronomy born out of social rape…Intense hunger is seared in the collective memory…Poverty, absolute, extreme and degrading, has ironically been a stimulus for the Sicilian housewife to improvise a little something out of a lot of nothing…

§

Sleeping and eating in central Palermo, even for a brief week, it was impossible to pretend that we were in Fairyland. For every restored architectural masterpiece there are a score of crumbling wrecks, some of them equally deserving of preservation. Prosperity and poverty stare each other in the face. The dusty battered cars go where they will, pedestrians where they must. Washing hangs askew on the balconies of architectural gems. Antica Focacceria, the oldest and most respected eating place in the old city, is what Americans call a burger joint (except that over there, the touted spleen and tripe would end up in pet food).

Families have their own culinary traditions, but in the restaurants in which we ate there was an unvarying pattern of an antipasto (not a traditional part of a Sicilian meal), followed by a prima (usually pasta) and then a secunda (most typically fish) and then dessert. The norm could be narrowed even further: you might well start with caponata, then pasta con le sarde, proceed to grilled seafood (whether swordfish or cuttlefish would depend on what you were prepared to pay) and end with a rich dessert. The courses would follow each other with the rapidity of a New York greasy spoon—after eating the “whole thing” (like the man in the famous ad) in well under an hour, you could make the Alka-Seltzer Book of Records.

After a week of such fare we missed both vegetables and meat as stapes of the main course; our experience of these, as I’ve suggested, was not altogether happy. (Bear in mind that we were not dropping into restaurants at random, but had mostly chosen well-recommended places.)

§

But in the end, Sicily was yet another confirmation of the world-wide fact that poverty can be at least a transitory protection for indigenous cuisines against industrial invasion. In a pizzeria, we had a couple of cheap pizzas which were my first, since moving to England from the US, with a perfectly cooked base, the sort that allows you to bend a segment into a U-shape and hold it in your hand—knives and forks have nothing to do with pizzas!

One evening in Palermo we set out looking for a trattoria that had been recommended by one of our fellow tour members. Not quite certain of its location, we walked along a couple of streets near the Vucceria Market that were lined with cheap eateries just starting to serve dinner. Through the front doors they looked distinctly unappetising—would any have passed a health and safety check?—but the tables outside were beginning to fill up with ordinary people, some with decent-looking dishes already in front of them. None of these places were branded fast food chains, and their signs were so modest that you could scarcely tell where one ended and another began. It was a welcome change from the endless rows of culinary assembly lines in virtually every city in Europe and America. I thought to myself, if I had to eat in cheap joints for the rest of my life, Palermo might not be the worst city in the world in which to do it.

Finally, my profound and loving thanks to Mary. The whole trip was her treat.

©2006 John Whiting

POSTSCRIPT: I have many friends who love Sicily, but none who have expressed a desire to live there. If you want to know what it is like, read The Outside Chance, a Guardian report on the unlikely candidacy of Rita Bosellino for the Sicilian presidency. By the time you read this, she may have been elected or assassinated—or both.

NEXT Return to TOP Return to SICILY INDEX