![]()

Years of living (if you can call it living) under Ceausescu schooled the Romanians in the finer points of paranoia. When I was touring the Warsaw Pact countries before the Wall came down, Romania was the only country in which I felt everywhere an ominous presence, a funeral pall which hung over not only the bleakly mo numental city of Bucharest, but also the primitive countryside through which we were driven by bus to our concerts in Tirgu Mures and Sibiu. Peasant farmhouses along the road, elaborately festooned and brightly painted — as alluring as the witch’s gingerbread house in Hansel and Gretel — had broken windows patched with whatever materials were to hand. We stopped briefly at the birthplace of Vlad Dracul [left] in the substantial town of Sighisoara, deep in the Transylvanian forests; it was a comfortable bourgeois house whose modest well-proportioned rooms were almost reassuring. Not a bad sort, that Dracula. A bit of a thirst, perhaps . . .

numental city of Bucharest, but also the primitive countryside through which we were driven by bus to our concerts in Tirgu Mures and Sibiu. Peasant farmhouses along the road, elaborately festooned and brightly painted — as alluring as the witch’s gingerbread house in Hansel and Gretel — had broken windows patched with whatever materials were to hand. We stopped briefly at the birthplace of Vlad Dracul [left] in the substantial town of Sighisoara, deep in the Transylvanian forests; it was a comfortable bourgeois house whose modest well-proportioned rooms were almost reassuring. Not a bad sort, that Dracula. A bit of a thirst, perhaps . . .

I awoke in Sibiu on a Sunday morning to find the ancient town under a soft blanket of new snow. Everyone was bundled in their winter furs and on the way to church. I quickly got dres sed and followed them. I found the huge onion- topped church full both of worshippers and of the echoing magnificence of a Bach choral prelude. The service – in German – was a reverberating remnant of the Austro-Hungarian Empire.

sed and followed them. I found the huge onion- topped church full both of worshippers and of the echoing magnificence of a Bach choral prelude. The service – in German – was a reverberating remnant of the Austro-Hungarian Empire.

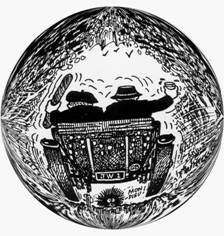

BUCHAREST UNDER Ceausescu was not a gourmet destination. The  only meal I ate in public which gave me any pleasure was at Caru’ cu bere [right], a huge old beer hall, the sort one finds in Munich, where we ate very Germanic "wieners und sauerkraut" fare. It was the only place which had any sense of reality or of continuity; others, no matter how old, felt somehow as though they'd just been knocked together for the night and would be gone in the morning. In those threatening days, life itself had this sort of impermanence.

only meal I ate in public which gave me any pleasure was at Caru’ cu bere [right], a huge old beer hall, the sort one finds in Munich, where we ate very Germanic "wieners und sauerkraut" fare. It was the only place which had any sense of reality or of continuity; others, no matter how old, felt somehow as though they'd just been knocked together for the night and would be gone in the morning. In those threatening days, life itself had this sort of impermanence.

Our last evening in Bucharest we were entertained by Myriam Marbe, a much-honored Romanian composer in her early fifties whose international reputation had helped her to hang onto the comfortable if threadbare family home. For much of the evening I conversed as an equal with her precocious and ravishingly beautiful sixteen-year-old daughter. It would be difficult for her to go to university, she told me; although tuition was free, the price of admission was in fact the gift of a new car to a government official.

Our last evening in Bucharest we were entertained by Myriam Marbe, a much-honored Romanian composer in her early fifties whose international reputation had helped her to hang onto the comfortable if threadbare family home. For much of the evening I conversed as an equal with her precocious and ravishingly beautiful sixteen-year-old daughter. It would be difficult for her to go to university, she told me; although tuition was free, the price of admission was in fact the gift of a new car to a government official.

The dining table was spread with a feast of salads, cold meats and pastries which must have depleted the food allowances of every one of the twenty or so artists who had banded together to entertain us. The wine – deep, well-aged, almost black – was nectar. How much of the precious food and drink would still be left after we departed? And what would they eat for the rest of the month?

A reminder of how desperately these people lived came at the end of the evening, when I discovered that my leather gloves were missing. I commented innocently that I must have dropped them somewhere in the bedroom where we left our coats, whereupon a search ensued which I gradually realized was only a face-saving ritual. Years later I told this story to another Romanian composer with whom I was working in Stuttgart. As I was leaving at the end of our week together he stopped me in the driveway and handed me a package. “We owe you this,” he said. It contained a pair of fine leather gloves. They have memories to match those of the old-fashioned high-topped Astrakhan hat I bought in Bucharest.

A COUPLE of years later I was having coffee with Myriam in a café on the Champs Elysées. Suddenly she leaned across the table and lowered her voice. “That man,” she whispered, “the one with the fedora, sitting at the bar. He is a member of the Romanian secret police.” Such paranoia! I had to laugh. She sat back and muttered something in Romanian, whereupon the man quickly turned around and stared at her. When we had finished our coffee and gone outside I asked her what she had said to attract his attention. She shrugged. “I only remarked,” she said, “that at least his socks were Romanian.” I was reminded of William Burroughs' definition of a paranoid which he had shared with an ecological conference in Aix. "A paranoid,“ he pronounced in his inimitable drawl, "is a person who is in possession of all the facts”.

-0-

1998: MYRIAM DIED last year – I learned that someone had composed an orchestral piece in her memory. At least she lived long enough to enjoy her country’s long-delayed liberation. Her daughter must have wangled an education somehow, for she is now a journalist in Holland. She shouldn't have any trouble getting interviews.

©1990 John Whiting