![]()

Paris sans football

1998

Paris Friday June 19 1998

A couple of months ago Matthew Brailsford, the indispensable man who banishes composer James Wood’s gremlins, told me that he would be going to Paris in June for the first performance of James’ latest piece. Assembled over two years within the subterranean Eiffel-Tower-like complexity of IRCAM’s prodigious technology, this would serve as an ideal occasion for a long weekend visit to Paris. Mary required very little persuasion to come along.

Two recent trips to northern France have taught us that Le Shuttle, which enables you to drive off of English soil and onto French within half an hour, makes La Belle France seem only a short shirt-Sleeve away, and so we booked once again for the brief afternoon journey. James then suggested that we might meet him at IRCAM (next door to the Pompidou Center) at six, take a short guided tour of its Eleusinean mysteries, and go on to eight-thirty dinner at

La Maison de Lozere . This is one of his favorite Latin Quarter restaurants, specializing in the robust peasant food of a rapidly depopulating corner of the Massif Centrale. A few of its departing cooks have set up outposts such as this in the world’s great centers of gastronomic transience.

Two recent trips to northern France have taught us that Le Shuttle, which enables you to drive off of English soil and onto French within half an hour, makes La Belle France seem only a short shirt-Sleeve away, and so we booked once again for the brief afternoon journey. James then suggested that we might meet him at IRCAM (next door to the Pompidou Center) at six, take a short guided tour of its Eleusinean mysteries, and go on to eight-thirty dinner at

La Maison de Lozere . This is one of his favorite Latin Quarter restaurants, specializing in the robust peasant food of a rapidly depopulating corner of the Massif Centrale. A few of its departing cooks have set up outposts such as this in the world’s great centers of gastronomic transience.

Our train reservation is for 3:30, too late to make the three-hour journey to Paris, then through the city to our hotel and back to IRCAM by 6:30. But Le Shuttle, with trains leaving every half-hour, are usually laid back about when you show up, so we aim at a new departure time of about 1:30. The lines of cars at the check-in points seem unusually long—perhaps related to the minor sporting event which France is hosting at the moment. (World Cup? Is that some sort of gluwein festival?) As we approach the window a TV monitor informs us that there will be a two hour wait. “There is a signal problem,” the girl at the window explains in the precise but offhand manner she might employ to tell us that the tunnel is flooded and a priest administering last rights by mobile phone.

To help us wile away the time in a manner which will be profitable to the management, we are all herded into the parking lot adjacent to the duty free shop. There are no spaces left and so we leave our car sitting at the side of the road in the spot where we’re blocked in the stationary traffic and stroll into the shopping/dining area, which is as crowded with people as the parking lot is with cars. They are remarkably good-tempered, considering that the bridge to France upon which they depended has suddenly collapsed into the waves beneath their feet. One family we talk to have already been waiting for two hours and expect to be waiting for two more. Children are running about amusing themselves, not angry or impatient but simply filling up the time with energetic activity. Outside the main entrance a team of Morris dancers are practicing their steps, striking their rods on the pavement as they perform their intricate maneuvers. It’s all an object lesson in civilized human adaptation.

The primary slogan of the late twentieth century is, WHEN IN DOUBT, SHOP. What infantile behavior! Mary and I would never make unnecessary purchases simply because we had time on our hands. Anyone who claims to have seen us spending sixty quid at the Tie Rack duty-free sales is lying through his teeth.

We remain eternally optimistic. For a couple of hours we are able to count the minutes to our promised departure time. When we finally board a train, three-and-a-half hours after our arrival, we have only had an extra 90 minutes of frustration. Then, not knowing that the train will be an extra half-hour late in leaving, we only have to suffer minute-by-minute frustration rather than the full weight of a known quantity. Free will, Wittgenstein informs us wryly, consists in the fact that the future is not known.

BUT EVEN our habitual optimism gives way to the fact that a three-hour journey to Paris, beginning at seven-fifteen, will not get us to and then through the city and back to a Left Bank restaurant that takes last orders at about ten. Matthew gets on his mobile phone—that abomination I so loathe except when it is indispensable—and makes arrangements to meet James at L’Ecurie, our favorite little Paris grill at the north edge of the Latin Quarter, which readers of Through Darkest Gaul will know all about.

While Mary’s knuckles turn white, I cut the three-hour drive to two-and-a-half. And then comes the Lottery that Nobody Wins—the drive through central Paris. From the A1 autoroute you cross the peripherique at the Porte de la Chapelle and are encouragingly directed to Paris Centre, but after you’re on the Rue de la Chapelle you’re on your own. If you continue straight ahead onto the Rue Marx Dormoy you’re suddenly adrift in a sea of one-way streets which, if you follow your instincts, are likely to point you back inexorably towards Calais. The necessary, the cr ucial act is to take a tiny unmarked left fork which puts you onto the rue Phillip-de-Girard [right], a one-way street so narrow that you know it can’t be the right way. But, like devious French logic, it takes you straight to your destination while hundreds of convention-bound travelers, slaves to the obvious, are ricocheting aimlessly from impasse to impasse. The boulevards were cut through Paris for the passage of soldiers, not citizens. The best routes through the inner city are a well-guarded secret.

ucial act is to take a tiny unmarked left fork which puts you onto the rue Phillip-de-Girard [right], a one-way street so narrow that you know it can’t be the right way. But, like devious French logic, it takes you straight to your destination while hundreds of convention-bound travelers, slaves to the obvious, are ricocheting aimlessly from impasse to impasse. The boulevards were cut through Paris for the passage of soldiers, not citizens. The best routes through the inner city are a well-guarded secret.

We’re almost to the Pont Notre Dame when a misleading sign takes us east on a one-way boulevard. It’s time to pull over, find our place on the map (which we accomplish without coming to blows), and get back onto the route. Three blocks from our hotel our way is suddenly blocked  by what must be a thousand roller-bladers who are “reclaiming the streets”. Escorted by similarly shod gendarmes, the soft swish of their well-oiled wheels swells to a river-flow. A panorama of weird and wonderful costumes passes by in a whirl of flotsam and jetsam. It is another of the many instances of street theatre that we always encounter in Paris. No way around it; nothing to do but wait for the tidal wave to recede.

by what must be a thousand roller-bladers who are “reclaiming the streets”. Escorted by similarly shod gendarmes, the soft swish of their well-oiled wheels swells to a river-flow. A panorama of weird and wonderful costumes passes by in a whirl of flotsam and jetsam. It is another of the many instances of street theatre that we always encounter in Paris. No way around it; nothing to do but wait for the tidal wave to recede.

The heat, even at this hour, is stifling. By the time we’re at our hotel it’s past eleven. No legal place to park. The solitary attendant at an empty all-night garage insists that there is pas de place; he has probably decided that I’m one of those English football hooligans. We’ll worry about parking tomorrow. As for getting to L’Ecurie, we’ve no energy left for anything more strenuous than ordering a taxi.

We seem to have served our allotted sentence of frustration for today. The cab arrives quickly and takes us straight to the restaurant within a few minutes, and there is James at an outside table, slowly working his way through a succulent hunk of lamb. Our glass of sangria arrives, followed by the usual basket of heavy dark bread with its bowl of formidable aïoli, and we can relax and wait for the blue cheese salad. Life is bearable once more.

This is the first time I’ve been back to L’Ecurie since Through Darkest Gaul came out. Friends have come, taking copies with them—one even read aloud from it, translating it into French—but I haven’t been able to give the restaurant its own copy. Through James as interpreter, I present it to Madame at the end of the meal. She is touchingly grateful and starts to tear up the bill for our dinner, but I stop her. I don’t want to get into a quid pro quo relationship with the proprieters of my favorite places to eat and sleep. I realize that there are those who literally depend upon such largesse for their bread and butter, but that isn’t, as one used to say so economically but eloquently, my scene.

By the time we’ve licked the last of the cassis sorbet out of the dish and polished off the extra calvados that Madame has forced upon us (very little force required), the Metro has stopped running. “No problem,” says James, “there’s a taxi rank on the Boul Mich.” It proves to be full of young revelers with the same idea. This isn’t London, so the concept of queuing, i.e. waiting one’s turn, is unknown. After several unsuccessful attempts we elbow our way to an arriving cab and call out our destination, whereupon the driver dismisses us with a laconic insult and takes a couple just behind us. Again we are reminded that shabby, stodgy old London has certain unique virtues, such as a black cab’s legal obligation to take you wherever you want to go (within a wide radius). The French, by and large, are polite, the Brits considerate. It’s a distinction worth contemplating.

Back to L’Ecurie, where a couple of phone calls make it clear that on this festive night it’s a taxi free-for-all. We resign ourselves to a half- hour walk back to the hotel down the rue Mouffetard, the Latin Quarter’s old market street which now devotes itself largely to supplying the various needs of those who can’t bear to go to sleep. It’s 2 a.m. and we appear to be the only people in Paris who are even thinking about retiring.

hour walk back to the hotel down the rue Mouffetard, the Latin Quarter’s old market street which now devotes itself largely to supplying the various needs of those who can’t bear to go to sleep. It’s 2 a.m. and we appear to be the only people in Paris who are even thinking about retiring.

Saturday June 20 1998

The alarm at 9 a.m. brings with it a reminder of the utter stupidity of bringing a car to Paris. The obstinate peasant at the parking garage, which is still empty, reiterates his claim that there are no available spaces. Given his ability to deny the evidence of our senses, he would make a good parish priest.

Until another garage can be located, I must put the car in a payant space on the street. But even at this early hour on a Saturday, all the spaces are full. And then the centime drops: one does not pay at the weekend. A drive round the block reveals an empty space which someone has just left, and we’re set up until Monday morning, when we return to London. Fools are protected by God; otherwise not so many of us would survive.

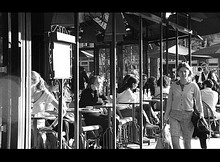

Back to the hotel, where we learn that breakfast must be ordered the night before. No matter, this is Paris, where every boulevard is lined with tables at which a fearsomely e xpensive demitasse is “key money” that gives you the right to your chair for as long as you choose to occupy it. Matthew has gone out, so Mary and I stroll along the avenue des Gobelins and settle at the Café Canon at a table which is at the very apex of the corner with the boulevard St-Marcel, its 270-degree angle of vision making it the perfect vantage point for people-watching. From there we scrutinize the hikers, the marchers, the trudgers and the strollers, commenting on their dress and speculating on their errands. There goes a chic young lady in a simple straight dress, nothing unusual about her except the nonchalant perfection that makes you think immediately of Paris. And there’s a neat young man in Levis and a trendy T-shirt, noteworthy for the fact that his hair is undyed and his nose unringed. A nondescript but unobjectionable bit of period French pop music is playing on the cafe loudspeakers—no booming bass, no screaming vocals. We’re caught in a snapshot of urban nostalgia, European city life as one remembers it from a quarter-century ago. The outer fringes of urban middle-class Paris are “cool” in the old-fashioned sense: relaxed, laid back, unaggressive. It’s pleasant to sit here for an hour over our coffee and croissants.

xpensive demitasse is “key money” that gives you the right to your chair for as long as you choose to occupy it. Matthew has gone out, so Mary and I stroll along the avenue des Gobelins and settle at the Café Canon at a table which is at the very apex of the corner with the boulevard St-Marcel, its 270-degree angle of vision making it the perfect vantage point for people-watching. From there we scrutinize the hikers, the marchers, the trudgers and the strollers, commenting on their dress and speculating on their errands. There goes a chic young lady in a simple straight dress, nothing unusual about her except the nonchalant perfection that makes you think immediately of Paris. And there’s a neat young man in Levis and a trendy T-shirt, noteworthy for the fact that his hair is undyed and his nose unringed. A nondescript but unobjectionable bit of period French pop music is playing on the cafe loudspeakers—no booming bass, no screaming vocals. We’re caught in a snapshot of urban nostalgia, European city life as one remembers it from a quarter-century ago. The outer fringes of urban middle-class Paris are “cool” in the old-fashioned sense: relaxed, laid back, unaggressive. It’s pleasant to sit here for an hour over our coffee and croissants.

WE’VE ARRANGED to meet Matthew for lunch in the Place des Vosges. One of the most beautiful squares in the world (Parisians think it’s the most beautiful), it was almost derelict [left] when Mary and I discovered it in the early 70s. Now its long arcades surmounted by uniform dormer-windowed brick-and-stone facades are mostly restored and highly fashionable. I’m tempted to prefer it as we knew it, but what a perversion: I’m as bad as the Victorians, with their love of deserted Gothic ruins. Today, lined with fearsomely expensive shops and clubs instead of the residences of the aristocracy, it’s nevertheless more “tasteful” than when its open square, now a beautiful public garden with perfect flower beds between rows of topiary elegance, was the scene four centuries ago of noisy tournaments and jousting matches.

WE’VE ARRANGED to meet Matthew for lunch in the Place des Vosges. One of the most beautiful squares in the world (Parisians think it’s the most beautiful), it was almost derelict [left] when Mary and I discovered it in the early 70s. Now its long arcades surmounted by uniform dormer-windowed brick-and-stone facades are mostly restored and highly fashionable. I’m tempted to prefer it as we knew it, but what a perversion: I’m as bad as the Victorians, with their love of deserted Gothic ruins. Today, lined with fearsomely expensive shops and clubs instead of the residences of the aristocracy, it’s nevertheless more “tasteful” than when its open square, now a beautiful public garden with perfect flower beds between rows of topiary elegance, was the scene four centuries ago of noisy tournaments and jousting matches.

I’ve suggested that we meet for lunch at the Brasserie Ma Bourgogne, a sidewalk restaurant/cafe at the northwest corner which is much frequented, but not commandeered, by tourists. It has remained unchanged during the decade or more that I’ve been going there (and the last ten years have seen the destruction of many a culinary shrine!). Perhaps the best indication that they have not sold out to the tourist trade is the fact that they still resolutely refuse to accept credit cards.

Ma Bourgogne was already an institution half a century ago when Georges Simenon identified it as a favorite haunt of Inspector Maigret, who embodied the author’s love of classic bourgeois cuisine. This was so heart-felt, and so detailed, that Robert Coutine could recreate the recipes in a splendid little volume with Simenon’s imprimatur. You’ll still find this sort of fare at Ma Bourgogne: simple old-fashioned dishes that elsewhere have become clichéd and, in the process, cheapened and corrupted.

Today is so witheringly hot that I opt for a cold lunch: gazpacho followed by steak tartare and finishing with cantal cheese. How boring this could be! And yet the cold soup is dense, rich and spicy, with identifiable fragments of ripe tomato, pepper and cucumber. The robust steak tartare has the deep red color and the melt-in-the-mouth texture of expensive lean meat, not the tough fatty scrag ends that are so often ground through the mill in tourist traps. And finally, the cantal: rich and crumbly like Mrs. Montgomery’s farmhouse cheddar, with a thick moldy crust, just as Quentin Crew describes it in Foods from France—a million miles from the factory-made blocks of rubber that now pass for cantal in the supermarkets. I comment to the waiter on its quality and he affirms that it still comes to them straight from the mountains of the Auvergne (perhaps from the high pastures of Jules Porte himself).

AFTER LUNCH Mary and Matthew take off for the Louvre, while I opt for the afternoon rehearsal of James’ new piece, more than a little influenced by the fact that IRCAM’s subterranean premises are air-conditioned. What a relief to pass over the little bridge at the edge of the place Georges Pompidou and enter the cool sanctum sanctorum of electroacoustic music. The espace de projection is two floors down in a space-age elevator, and then another two long flights of stairs into the bowels of the earth. Like Dante’s Inferno, the lower you go the colder it gets. On a scorcher like today, hell is indeed heaven.

AFTER LUNCH Mary and Matthew take off for the Louvre, while I opt for the afternoon rehearsal of James’ new piece, more than a little influenced by the fact that IRCAM’s subterranean premises are air-conditioned. What a relief to pass over the little bridge at the edge of the place Georges Pompidou and enter the cool sanctum sanctorum of electroacoustic music. The espace de projection is two floors down in a space-age elevator, and then another two long flights of stairs into the bowels of the earth. Like Dante’s Inferno, the lower you go the colder it gets. On a scorcher like today, hell is indeed heaven.

A couple of other pieces are being rehearsed before James’ and the relief from the heat is so profound that I find myself nodding off. I haven’t seen either score or program notes so all I know is that Mountain Language is based in some way on the Tirolean Alps and is scored for alphorn, percussion and keyboard-driven samplers (including alphorn samples played by John Kenny), whose sounds are Ambisonically distributed. Without documentation I’m not sure what’s going on and the sound distribution doesn’t seem nearly so precise as I’ve been led to expect. Perhaps my brain will be functioning more efficiently in a couple of hours.

The printed program, when I get to see it an hour before the concert, mercifully includes James’ notes in their original English, and I discover that there is both spatial and temporal precision in the piece’s organization. The sampled sounds are of alphorn, cowbell and church bell and are gradually transmogrified, with no transposition except by octaves, into complex melodic patterns derived from James’ analysis of over a hundred birdsongs. The piece’s duration corresponds to a single day-cycle—from night, through morning church bells and dawn chorus, a gradually climaxing storm, a busy late afternoon, church bells announcing evening prayer, sunset, and back to night.

The spatial distribution is also exact, corresponding to a circular graph on which are plotted the locations of eighty-nine peaks surrounding the Tirolean village of Ishgl. Fortunately, very soon after the piece begins I happen to tilt my head back, whereupon the sound distribution clicks solidly into place and I hear little percussive bell sounds tinkling at precise points on the ceiling of the hall, like twinkling stars in a clear night sky. But of course I should have anticipated this: the human ear is incapable of hearing sounds from the rear with any accuracy, and so the amplitude and phase relationships between front and rear speakers upon which Ambisonics depend is corrupted unless you are flat on your back and hearing all the signals as *frontal* images. (Fortunately, most sound projection doesn’t rely on such complex precision.) A performance of this piece with space for an audience to stretch out, accompanied by a projection of the mountain map onto the (hopefully plain) ceiling, would make everything click into place. A viable alternative, particularly in a hall with balconies, would be a *vertical* array of speakers across the front, with the image inverted so that “north” was to the top. An enormous vertical projection screen for the graph would then be an expensive but worthwhile option.

One of the delights of an IRCAM electroacoustic concert is the pure undistorted sound projection at sensibly undeafening levels. As if to deceive us, the last piece on the program is a new Jonathan Harvey quintet for harp, oboe and string trio, a totally acoustic work in which instrumental harmonics produce the effect of perfectly tuned ring modulators, utterly free of breakthrough and intermodulation distortion. If such a treatment device existed, it would be the Pearl of Great Price for which, like the Biblical merchant, I would sell all that I have.

USUALLY AFTER an IRCAM concert we adjourn to the upper floor of the nearby Restaurant Beaubourg, but today is so sweltering that we have opted for a sidewalk cafe just across the place de Georges Pompidou. I mistrust them as soon as we arrive; it is obvious that, in spite of our reservation, they haven’t saved us a table and we must wait in the hot stuffy bar as if we had showed up unannounced. The food, alas, echoes the service. I make the mistake of ordering the same starter and main course I’d eaten for lunch: gazpacho followed by steak tartare. Both, unsurprisingly, prove to be the worst I’ve ever experienced. The gazpacho, bland and tasteless, is so diluted with water and then thickened with breadcrumbs that the color has faded to an anemic pink, and the nondescript steak tartare—God knows how long it has been breeding bacteria!—Is the color of the rancid fat from which it was probably made.

This is exactly the sort of cynical, unscrupulous pigsty which can survive in Paris because, with its transient tourist clientele, it need never feed anyone more than once. While I’m wondering what I dare to order for desert, Mary points out to Matthew and me that the metro is about to close down and that, if we don’t leave immediately, we’re liable to experience another unsuccessful search for a taxi followed by an hour’s hike back to our hotel. With firm pressure on our indifferent waiter we settle our part of the bill and arrive on the platform just four minutes before the last train. Thank you, Mary, for paying as much attention to the inexorable clock as to the brilliant conversation!

Brasserie Ma Bourgogne, 19, place des Vosges (4th), TEL: 01-42-78-44-64

Sunday June 21 1998

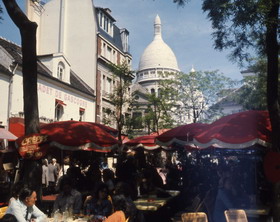

This morning Matthew would like to see a bit of Paris, so Mary and I—both teachers at heart—gladly offer to show him around. (A teacher is a student who is one lesson ahead of the other students.) We’ve finished breakfast by 9:30 and have a luncheon reservation for one o’clock, which gives us three-and-a-half hours. After a hasty consideration of the alternatives, we decide on Montmartre and the Sacre Coeur. This tourist shrine is usually approached en masse [sic] up the little funicular railway from the Square Willette, so we opt to sneak up on it from behind, arriving at the metro station Lamarck Caulaincourt and climbing up the steep hill to the St. Vincent cemetery and the last remaining vineyard in Paris. Pro-rated by an accountant against alternative property utilization, these must be the world’s most expensive grapes!

We prove once again the theorem that tourists have a mutual attraction such that, the greater the number, the more densely they pack together like iron filings about a magnet. The picturesque streets surrounding the cemetery, even the Lapin Agile with its long-standing literary associations, are virtually deserted. As we approach the outer edges of the Place du Tertre by way of the rue des Saules, we can see the edge of the Sunday-morning crowd, like the fringes of a jellyfish, undulating around the souvenir shops. When we reach the rue Norvins we are drawn in as if by its tentacles, caught up in the seething mass of humanity. The only still points in this swirling world are the tableau vivant statues, white-faced performers in elaborate costumes who stand motionless by the hour. There are saints of both sexes, a bride-and-groom to surmount an enormous wedding cake, Harlequin figures poised, like the Roman statue of the Laocoön, on the cusp of a denouement that never arrives. Only their eyes move, beseeching you to drop a coin into the boxes at their feet.

We prove once again the theorem that tourists have a mutual attraction such that, the greater the number, the more densely they pack together like iron filings about a magnet. The picturesque streets surrounding the cemetery, even the Lapin Agile with its long-standing literary associations, are virtually deserted. As we approach the outer edges of the Place du Tertre by way of the rue des Saules, we can see the edge of the Sunday-morning crowd, like the fringes of a jellyfish, undulating around the souvenir shops. When we reach the rue Norvins we are drawn in as if by its tentacles, caught up in the seething mass of humanity. The only still points in this swirling world are the tableau vivant statues, white-faced performers in elaborate costumes who stand motionless by the hour. There are saints of both sexes, a bride-and-groom to surmount an enormous wedding cake, Harlequin figures poised, like the Roman statue of the Laocoön, on the cusp of a denouement that never arrives. Only their eyes move, beseeching you to drop a coin into the boxes at their feet.

The Place du Tertre is lined with shops and cafes, its center filled with tables jammed edge-to-edge, a solid canopy of awnings providing continual protection from the sun or the rain, whichever is prevalent. I don’t remember it being so utterly tourist-inundated twenty years ago, but I must be mistaken; there’s a photo dating from 1914, when Picasso was at work not far away on his Demoiselles d’Avignon, showing the tables even more densely packed, though without any protective covering. Tourists were tough in those days.

The Place du Tertre is lined with shops and cafes, its center filled with tables jammed edge-to-edge, a solid canopy of awnings providing continual protection from the sun or the rain, whichever is prevalent. I don’t remember it being so utterly tourist-inundated twenty years ago, but I must be mistaken; there’s a photo dating from 1914, when Picasso was at work not far away on his Demoiselles d’Avignon, showing the tables even more densely packed, though without any protective covering. Tourists were tough in those days.

The sweltering heat is already upon us and we join the crowds entering the great basilica of the Sacre Coeur, not out of religious devotion or even aesthetic curiosity, but longing for the perpetually cool air within. We can only just get inside the door; a service is ending and within a few minutes we are swept outside by the departing congregation.

We take a few brief moments to admire the panoramic view of Paris from the steps. Across the city to the southwest the skyline is dominated by the enormous black shaft of the Tour Montparnasse, an architect’s impression of the mysterious extra-terrestrial artifact which cows the humanoids at the opening of 2001. The finest view of Paris, say the Parisians, is from its apex—the only point from which the building itself is invisible.

Back through the Place du Tertre, where both sidewalk artists and chefs are working hard to upset the digestion, and along the rue Norvins to one of our favorite little parks, the Place Marcel Armé. As you come upon it at the corner with the rue Girardon, you find yourself looking back and down on a solid stone wall through which is emerging the bronze figure of a man. He is slender, haughty and ascetic: perhaps a minor but respectable civil servant. The upper part of his body and his head, with its high-cheek-boned aquiline features, has already appeared, leaning forward, together with an outstretched left arm and a high-stepping right leg, visible from just beyond the knee. You stop and stare, waiting for the rest of the body to follow. Spectators seem to feel a kinship—his outstretched fingers are shiny from ritual grasping.

Back through the Place du Tertre, where both sidewalk artists and chefs are working hard to upset the digestion, and along the rue Norvins to one of our favorite little parks, the Place Marcel Armé. As you come upon it at the corner with the rue Girardon, you find yourself looking back and down on a solid stone wall through which is emerging the bronze figure of a man. He is slender, haughty and ascetic: perhaps a minor but respectable civil servant. The upper part of his body and his head, with its high-cheek-boned aquiline features, has already appeared, leaning forward, together with an outstretched left arm and a high-stepping right leg, visible from just beyond the knee. You stop and stare, waiting for the rest of the body to follow. Spectators seem to feel a kinship—his outstretched fingers are shiny from ritual grasping.

On a building which joins the wall at right angles is a plaque explaining that this narrow little park eponymously honors the author of a popular fantasy about a man who could walk through walls. Just overhead a nd a couple of yards to the right is another, older plaque dedicated to the memory of a great man who seems to have walked through this wall in the opposite direction and never returned. D.E. Ingelbrecht, who lived nearby, is here identified as a composer and a conductor, but it is the latter for which he is remembered, if at all. Throughout the fifties he committed to disc some of the most delicate, witty, sophisticated and thoroughly French performances of Debussy and Ravel that anyone ever accomplished. Most of them came out on the Ducretet-Thompson label and have long since disappeared; a few were live performances at the Theatre de Champs-Elysées which have been released on CD. Only a few devotees seem to remember him, including the fine English composer/ conductor Oliver Knussen, who gave me tapes of a couple of performances I was missing. I must remember to check at Tower Records in the Louvre shopping mall to see if any more have appeared.

nd a couple of yards to the right is another, older plaque dedicated to the memory of a great man who seems to have walked through this wall in the opposite direction and never returned. D.E. Ingelbrecht, who lived nearby, is here identified as a composer and a conductor, but it is the latter for which he is remembered, if at all. Throughout the fifties he committed to disc some of the most delicate, witty, sophisticated and thoroughly French performances of Debussy and Ravel that anyone ever accomplished. Most of them came out on the Ducretet-Thompson label and have long since disappeared; a few were live performances at the Theatre de Champs-Elysées which have been released on CD. Only a few devotees seem to remember him, including the fine English composer/ conductor Oliver Knussen, who gave me tapes of a couple of performances I was missing. I must remember to check at Tower Records in the Louvre shopping mall to see if any more have appeared.

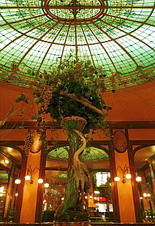

BY THE TIME we have finished contemplating the permeability of stone and the imperviousness of time, we must hurry off to lunch. I had no difficulty persuading Mary that the place we must go is the Brasserie Bofinger just off the Place de la Bastille; one glimpse of its fine glass-domed art nouveau interior and its ample seafood menu were enough to do the trick. (Also, not inconsiderable in this wilting heat wave, was it’s air-conditioning.) Like the wonderful Cafe Landmann in Vienna, dating from a similar era, it has been painstakingly restored to all its former glory; but unlike the latter, the kitchen has been amply staffed and equipped to do justice to the ambiance.

Bofinger has much history behind it. From its opening in 1864, it was the first place in Paris to serve  draught beer, whose continually flowing suds lubricated its early success. In 1919 it was expanded into the adjacent buildings, and the present design, dominated by the sweeping curved staircase and the florally ornamented stained-glass dome, was jointly created by the architect Legay and the interior designer Mitdgen. (Even the men's toilet is worth an architectural visit.) It went from strength to strength and in 1925 was declared by chef des chefs Curnonsky to be “one of the best brasseries in Paris”. It went off form after W.W.II but was bought in 1982 by a consortium who restored the gloss both to its interior and to its cuisine.

draught beer, whose continually flowing suds lubricated its early success. In 1919 it was expanded into the adjacent buildings, and the present design, dominated by the sweeping curved staircase and the florally ornamented stained-glass dome, was jointly created by the architect Legay and the interior designer Mitdgen. (Even the men's toilet is worth an architectural visit.) It went from strength to strength and in 1925 was declared by chef des chefs Curnonsky to be “one of the best brasseries in Paris”. It went off form after W.W.II but was bought in 1982 by a consortium who restored the gloss both to its interior and to its cuisine.

With its enormous daily turnover, Bofinger is the place to go for raw or minimally cooked seafood. It is as though an inlet from the sea flowed straight through its kitchen. When I was first taken there a few years ago by my old friend Dave Robertson, the newly-appointed musical director of Ensemble Intercontemporain, we shared a plateau de fruits de mer which quivered with shellfish so fresh that they thought they were still tucked away on the seabed. On a later visit I had a simple boiled crab (perplexingly identified in the menu as torteau, not to be confused with tortue, or tortoise) so sensational as to set it qualitatively apart from the scores I had eaten on both sides of the Atlantic.

Not having specified the main dining area, we are escorted to the upstairs dining room, somewhat dark and somber in decor and rather noticeably hotter. But I enjoy the murals, which are a part of the room’s redecoration in 1930 by Jean-Jaques Waltz, familiarly known as Hansi. Portraying typical Alsatian rural scenes, they are a reminder of the brasserie’s dominant cuisine, which, together with the shellfish, is the charcouterie of Alsace. Besides, it’s always a pleasure to sit in a room which no one has seen fit to modernize since before I was born.

I opt for another crab, preceded by a half-dozen large fine de claires oysters. “They say oysters are a cruel meat,” wrote Swift, “because we eat them alive; then they are an uncharitable meat because we leave nothing to the poor; and they are an ungodly meat, because we never say grace.” If he was right, then I am damned on all three counts. These are sweet and enormous, and I wolf my way through them as though the ice platter were about to be whipped away for the next diner.

When the crab arrives, its body proves to be more densely packed with moist tasty meat than any I’ve encountered, but the claws are disappointingly dry and the points do not come easily out of the shell. It’s a reminder that, when you rely on natural ingredients served with a minimum of preparation, you are at the mercy of nature. Unlike a multi-stage recipe, you can’t add flavorings to dull flesh or inject fluid into dry claws. Even the most reliable sources will occasionally yield disappointment; ordering a crab or a lobster is an act of faith.

AFTER THE RICH crab, a cold, sharply acidic sorbet de cassis is both cooling and cleansing. Then a demitasse of coffee, and back into the oppressive heat. We head immediately for the underground shopping center attached to the Louvre, principally because it is very effectively air-conditioned. The front of cool air as we round the corner from the metro corridor is a foretaste of heaven. I could stay and window-shop forever.

Mary and Matthew both have a bit of serious shopping to do, so we make arrangements to meet in half an hour. I head for the Virgin Megastore to see what sort of a selection they have. The CD-ROM multimedia section is pitiful: mostly games and children’s edutainment, with a few feet of shelf space devoted to a spotty collection of art appreciation and virtual travel. There aren’t more than three or four packages I’d accept as a gift.

The classical CD section, way at the back of the store, is large but devoted most prominently to the display of Three-Tenors-type best-sellers. The “contemporary” section consists principally of multiple copies of the latest Philip Glass and Kronos Quartet releases; it seems to be regularly weeded out, so that there are no old obscure titles that you might have been seeking for years. If you’re an unknown composer you only get one bite of the cherry; then it’s back onto the street to make way for the next batch of hopefuls.

I spend a lot of time going through the Debussy and Ravel sections. There’s not a single re-release of an Ingelbrecht recording, including the few that were previously available on a French label. Ou sont les neiges d’antan?

Finally we must leave our gelid Elysium. Matthew is headed for IRCAM, where James has promised to show him around; Mary and I only want to return to the hotel and fight over who gets first crack at the bathtub full of cold water. As to dinner. . . we’re so stuffed that we may never eat again.

BUT BY eight o’clock our digestive juices are stirring. Hunger can be learned, and we’ve been on a crash course. A quick search reveals that most of the restaurants in the area are closed on Sunday night; furthermore, those that are open seem to be engaged in a mammouth exercise to frighten away the devil with loud noise. Everywhere on the sidewalks are small amplified pop groups, their cheap PAs turned up to distorted maximum, like an electronic travesty of Charles Ives’ multidirectional marching bands. Perhaps the ever-trendy mayor has decreed a new Sunday night rave.

I report back to Mary with the discouraging news. And then it occurs to us that L’Ecurie is down a quiet little side street and we’re only a few minutes away on the metro. We’re off like a shot.

Sure enough, L’Ecurie hasn’t joined in the general mayhem and the decible levels from around the corner are tolerable. Furthermore, there’s been a break in the weather, with a few spots of rain which we have to wipe away from our outdoor table and chairs. We guzzle the sangria, tuck into the bread and aïoli and order a starter of grilled marinated peppers and tomatoes, to be followed by a serving each of super gambas with a baked potato and an order of pommes frites. The gambas are enormous, there are four on each plate and, due to a slight misunderstanding, two massive baked potatoes arrive along with the fries. I’ve been in training for years and can get through it all with scarcely a burp, but Mary stops short of the last king prawn. On a sudden impulse, she offers it to a charming French couple at the next table with whom we’ve exchanged a few pleasantries. The lady gladly accepts and, although she’s just had desert, tucks straight into it as though she’s been on a hunger strike. In further conversation they remind me that today is June 21st, the midsummer solstice, which France has made an official occasion for all-night revelry. Of course! I was here for it two years ago, just before Mary & I drove off in the rain to the Île de Ré. Being in an expensive hotel at Chatelet, I was unable to get any sleep; this time our cheap and cheerful hostelry is tucked down a side street where we’ll have no trouble. Sometimes you have to pay through the nose for inconvenience.

Meanwhile I must go inside to the “hommes” and Madame, to whom I’d given a copy of Through Darkest Gaul a couple of nights before, offers to show me the lower levels of the restaurant. We go down a narrow flight of irregular twisting stairs with zero headroom to a multi-vaulted space like a wine cellar containing another half-dozen tables. She leads me across to a door marked privée, and we’re headed down still more precipitous steps into a Romanesque vault generously containing a long trestle table set for maybe twenty people. What a space to hold a soirée, and what a kitchen to cater for it! If I were rich I’d EuroStar a score of my friends over for a day and throw a Sunday luncheon party at L’Ecurie!

go down a narrow flight of irregular twisting stairs with zero headroom to a multi-vaulted space like a wine cellar containing another half-dozen tables. She leads me across to a door marked privée, and we’re headed down still more precipitous steps into a Romanesque vault generously containing a long trestle table set for maybe twenty people. What a space to hold a soirée, and what a kitchen to cater for it! If I were rich I’d EuroStar a score of my friends over for a day and throw a Sunday luncheon party at L’Ecurie!

Back upstairs I burble to Mary and the French couple about the subterranean wonders. Though they’ve lived in the area for many years and have raised their children here, they are unaware of the existence of the lowest level. As we pay our bills and prepare to leave, they invite us to come to their nearby apartment for a drink. On the way we pass Le Berthoud, Suzanne Knych’s restaurant which I recommended in Through Darkest Gaul. Though it’s only a couple of minutes from their door and they have heard good things of it, they’ve never been there. It’s the usual story. People come to London and drag me for the first time to restaurants they’ve traveled halfway around the world to visit.

Their flat is three floors up in an old house and quintessentially Parisian: many tiny rooms with tiny beds, coffered ceilings, densely figured wallpaper; formal, upright, minutely carved, well-seasoned furniture. He is an engineer who has lived and worked in South America and he offers me a Peruvian rum from a mysterious bottle. I accept it bravely and am amazed to find it smooth and mellow beyond belief, despite an obviously high alcoholic content. There are few pleasures so great as a truly interesting taste you’ve never even heard of.

It’s after midnight before we tear ourselves away, not wanting yet another photo-finish with the last train. Our hosts give us a card and offer to put us up any time we come to Paris. What naive innocence! I’m already planning the next trip. By the time I leave them, The Man who Came to Dinner will seem a passing shadow. . .

Bofinger, 5-7, rue de la Bastille, Tel: 01-42-72-87-82

Monday June 22 1998

It’s Monday and our Passport to Paradise is about to expire. The reservation on Le Shuttle from Calais is for 3:55 p.m., but I’m not going to worry about that. If they give us any of la statique I shall remind them that their bit of signal static in the tunnel stole several hours off the start of our weekend. In the meantime, I’ve a nice lunchtime surprise for Matthew.

But before we leave Paris, a visit to a street market is essential. Like hedgerows, these are organic structures which take many years to form but moments to destroy. A quarter-century ago Mary and I strolled along the rue de Buci near St-Germain-des-Prés, marveling at whole tunas and great wheels of salers cheese that must have required a team of pallbearers to heave them into place (we’ve photos to prove it). Today its expensive Disneymarché ambiance is quaint and folksy, with uniformed attendants and designer carts.

The rue Montorgueil is the last remnant of Les Halles, the sprawling old produce market area that is now a huge park and underground shopping mall, flanked by the historic hubs of the law (le Chatelet) and the profits (la Bourse). Extending several blocks due north from the middle of the park, the old market street is still lined with ancient shops and stalls selling the messy, smelly things (such as unwrapped fish and cheese) that modern supermarkets don’t like to dirty their displays with.

Five francs in our parking meter, voracious after its weekend slumber, will give us two hours to get to the market and back before driving north. American friends assure me that they always ignore Paris parking tickets--one proudly boasts of a collection of several thousand dating back to the 80s, all unpaid--but I’m less sanguine. Now that the tunnel is open, I envisage a blue-uniformed flat-capped gendarme, with pencil-thin mustache, rapping on our door with his baton.

By nine-thirty we’ve reached the rue Montorgueil by metro and find ourselves standing in the middle of a virtually empty street. Not only is it Monday, when (I now remember) most of the markets are closed, but it’s the morning after the midsummer’s all-night revels. The quarter-millennium-old (!) Pâtisserie Stohrer with its little crown-decorated pastries is open, as are a couple of cheese and fish shops, but there’s not enough activity to have warranted a special trip. The stock of Whiting Gourmet Tours Inc. has just taken a nose-dive.

Nevertheless I feel confident that, after lunch, Matthew won’t sell short. One of the most neglected little jewels in the north of France is the medieval walled town of Senlis, just off the A1 autoroute above Paris. (Contrary to the rules, the final “s” is pronounced. It is not, as Tallulah Bankhead once remarked, “silent like the ‘t’ in [Jean] Harlow.”)

I discovered Senlis by accident years ago when I was working in Paris and needed a hotel with a protected garage for my van full of expensive sound equipment. It occurred to me that I might stay somewhere north of the city but within easy driving distance, and just before Charles de Gaulle airport the name Senlis leapt out at me. I pulled off the autoroute and found the reassuringly old-fashioned facade of the H

I discovered Senlis by accident years ago when I was working in Paris and needed a hotel with a protected garage for my van full of expensive sound equipment. It occurred to me that I might stay somewhere north of the city but within easy driving distance, and just before Charles de Gaulle airport the name Senlis leapt out at me. I pulled off the autoroute and found the reassuringly old-fashioned facade of the H otel du Nord. There were simple robustly furnished rooms with bidets, an old stone barn across the road which served as a lock-up garage, and best of all, a dining room with colorless walls and white tablecloths, an enormous (unrefridgerated) cheese trolley, and a blue multigraphed menu containing such démodé items as tripes à la mode de caen. It remained my favored Paris nesting place until the kitchen changed management and both the menus and the food became mass-produced.

otel du Nord. There were simple robustly furnished rooms with bidets, an old stone barn across the road which served as a lock-up garage, and best of all, a dining room with colorless walls and white tablecloths, an enormous (unrefridgerated) cheese trolley, and a blue multigraphed menu containing such démodé items as tripes à la mode de caen. It remained my favored Paris nesting place until the kitchen changed management and both the menus and the food became mass-produced.

The next morning I awoke well before breakfast, as I so often do, and went for a short walk. I discovered that the hotel was on the outer edge of an ancient wall. Once inside, I was in a maze of cobbled streets lined with stone houses, leading successively to a large open square with a splendid 12th century cathedral which had been added to with imagination and eclat over the next three centuries. Later visits with Mary revealed a lively town with a bustling Tuesday & Saturday market, devoted more to food than to cheap mass-produced clothes and gadgets.

BACK TO the present. Monday lunch in provincial France is always a problem, but the Michelin guide suggests Vieille Auberge, a small restaurant just off the main market street. When we arrive at the front door we are somewhat put off by an iron hitching-post in the form of a uniformed darky, hand outstretched. But then, the French are not well-tuned to such anthropological niceties.

Inside, we find that the dark dining room is empty and the few diners have opted for the garden courtyard. The lone waitress, who couldn’t be more bored, gestures towards a table for three which stands, without protection, in the hot midday sun. A request for a more sheltered location leads, first to a peremptory refusal, and then to the grudging allotment of another table close to an unsightly pile of unused garden furniture. She clears and sets it (you can hear the escaping breathe of her impatience), flings down our cushions, and departs. Once seated, we realize that the table is wobbly. As we try to improvise a method of stabilizing it I realize that we are under no obligation to stay where we are not wanted. So far as the restaurant is concerned, we are one with the despised negro who gave us his compulsory welcome. By instant agreement, we arise and depart.

Now we’re on our own. We find our way instinctively to the main square, in which, just opposite the front of the cathedral, is a beautiful old stone building unobtrusively occupied by a restaurant, with several outdoor tables laid for lunch. Those who are already dining look both discerning and satisfied--you can tell more than a little about a restaurant from the manner and mood of its patrons. The carte is as distinguished as the ambiance and includes a reasonable fixed-price menu of predominantly Italian dishes. Osso bucco alla milanese leaps out at me--one of those classic dishes which, in England, the greedy excesses of the food industry, together with governmental cowardice, have now denied us. Omelettes, soufflés, mayonnaise, unbleached tripe, ox-tail soup, T-bone steaks, rib roasts: some of these, we are solemnly advised, must not be made in the traditional fashion, others not at all.

The restaurant is called Scaramouche, but the chef is far from being a buffoon or a ne’er-do-well. My osso bucco has obviously had a long slow cook; it holds its shape on the plate but dissolves in the mouth like a cassoulet bean. As for the marrow: in England it is easier to obtain crack in a nursery playground than to buy this ambrosia from a butcher. I savor it long and attentively to add to my cornucopia of happy memories.

Mary is drawn to the a la carte pages, where she settles on an intriguing smoked eel paté for a starter and breast of duckling with cherries for a main course. The paté proves to be so simple and delicious as to warrant asking the ingredients, which the chef, through the waiter, is happy to reveal consists only of smoked eel and creme fraîche. The duckling/cherries combination which follows, an Escoffier cold classic, is none the worse for being hot.

Mary’s simple dessert wipes the field: a dish of warm roasted strawberries--still firm and holding their shape--together with a scoop of the house’s own rich vanilla ice cream. They have released just enough of their juices to form a delicious hot couli. Quick baking and then rapid cooling is a useful trick for hurrying along unripe fruit (often the only kind you can buy, even in season), including the savory fruits--avocados and tomatoes.

Even fruit without much flavor tastes better, if thus assisted, than anything you can buy in a package, especially if helped discreetly with a complimentary fruit liqueur. My Dad was fond of the story of the Kentucky planter entertaining a convention of teetotal Baptist ministers and discovering that they had inadvertently been served his private stock of bourbon-laced watermelon. When his butler was sent to retrieve it, back came the report that “They done ate it clean down to the rind and put the seeds in their pocket!”

While we’re having coffee a couple of splendid open horse-drawn carriages with top-hatted coachmen pull up in front of the church. A wedding? No, apparently they’re available to take tourists for a slow ride around town. But there are no tourists in evidence. They must be a few miles down the autoroute at EuroDisney. This two-horse joint will never make it big as a tourist magnet with such a quiet, subdued atmosphere--it’s just an old town with breathtakingly beautiful architecture, going about its business more or less as it has done for centuries. A perusal of a real estate agent’s window reveals that we could trade our modest semi in Hampstead Garden Suburb for practically anything available and still have enough left over to splurge in the mouth-watering local market on into the foreseeable future. No wonder that so many of us superannuated Brits are puting down roots across the channel. Soon the Welsh won’t be the only angry natives torching the interlopers’ holiday homes.

On the way back to the car I notice sadly that the best wine-dealer in town, an old family firm that specialized in unusual French wines not commonly available in the chain stores and supermarkets, has gone out of business, its once-distinguished façade plastered with pop posters. A recent survey by Omnivins reveals that more than half the French young adults in their early 20s claim they never drink wine; only one in twenty drink it daily. The preferred drinks are designer beers and spirits and, most of all, Coca-Cola and its many clones. While exports from the best French vineyards reach new heights, the home-bred support that created the industry is rapidly dissipating. Soon both the food and the wine that were so inseparably a part of the French character will be an exotic pastime for an international elite, while the mass of the native population eats and drinks the anonymous artifacts that have become the international norm. Even at the top end of the market, just what is “native cuisine”? Most of the beans that go into a cassoulet in the Languedoc are now grown in Argentina.

We’ll try to get back before the horse-drawn coaches carry advertising placards.

_______________________________

Le Scaramouche, 4, place Notre-Dame, Senlis, Tel: 03 44 53 01 26

©1998 John Whiting