2007 Last year a thread on eGullet reported an unfortunate dining experience equivalent to an endlessly repeated farewell recital, but this year a repeat visitor from Denmark tells me at length and in detail what I splended meal she and her husband have just had, measuring up to the standards set for them half a dozen years ago. I would like to think that Chez Gramond continues to be living history.

2007 Last year a thread on eGullet reported an unfortunate dining experience equivalent to an endlessly repeated farewell recital, but this year a repeat visitor from Denmark tells me at length and in detail what I splended meal she and her husband have just had, measuring up to the standards set for them half a dozen years ago. I would like to think that Chez Gramond continues to be living history.

Thirty years ago I reverently photographed the "cottage"

at 27 rue de Fleurus to which

Gertrude Stein and her brother Leo had moved in 1910, seven years after Gertrude

had come to Paris for a sojourn which would last the rest of her life, almost

half a century. (It was easy to gain access to the courtyard in those more

open days; the huge gates were not shut during daylight hours.)

Thirty years ago I reverently photographed the "cottage"

at 27 rue de Fleurus to which

Gertrude Stein and her brother Leo had moved in 1910, seven years after Gertrude

had come to Paris for a sojourn which would last the rest of her life, almost

half a century. (It was easy to gain access to the courtyard in those more

open days; the huge gates were not shut during daylight hours.)

I didn't know it at the time, but the compact two-story house was already

occupied by Jean-Claude and Jeannine Gramond, who in 1967 had taken over a

modest bistro  up the street at number 5, close to the western entrance of

the Luxembourg Gardens. (Patricia Wells confusingly conflates the two addresses

into one.) Today the Gramonds still occupy both premises. The Stein address

is identifiable by a plaque on the outer wall, but nothing can be seen beyond

the solid metal sheets which make the elaborate iron gates proof against visual

as well as corporeal invasion. The bistro, however, has a welcoming glass

conservatory projecting onto the sidewalk.

up the street at number 5, close to the western entrance of

the Luxembourg Gardens. (Patricia Wells confusingly conflates the two addresses

into one.) Today the Gramonds still occupy both premises. The Stein address

is identifiable by a plaque on the outer wall, but nothing can be seen beyond

the solid metal sheets which make the elaborate iron gates proof against visual

as well as corporeal invasion. The bistro, however, has a welcoming glass

conservatory projecting onto the sidewalk.

Once inside you feel as thou gh you had entered Dr. Who's tardis and were hurtling

back half a century towards post-war Paris. The Friday evening I showed up

for dinner I had the place to myself - no "modern" conversation

at adjacent tables to clash with the ancient lace tablecloths, the satin-striped

wallpaper and the fish tank in the front window - for company, not for cuisine.

When

I announced to Madame Gramond that I brought greetings from Marlena Spieler

of California, she went into the kitchen and brought her husband

to share the conversation.

gh you had entered Dr. Who's tardis and were hurtling

back half a century towards post-war Paris. The Friday evening I showed up

for dinner I had the place to myself - no "modern" conversation

at adjacent tables to clash with the ancient lace tablecloths, the satin-striped

wallpaper and the fish tank in the front window - for company, not for cuisine.

When

I announced to Madame Gramond that I brought greetings from Marlena Spieler

of California, she went into the kitchen and brought her husband

to share the conversation.

Some time later - it didn't matter when, for I was no longer in a clock-dominated universe - I settled down to a perusal of the menu. Quite audibly from the kitchen came the sounds of an old-fashioned French radio station, something rather like the BBC's Golden Oldies Radio 2. Ancient French pop music, with informal conversation in between - were they discussing the state of Paris since the liberation?

The carte was in itself a remarkable object, for it had been reproduced at

some time in the distant past on a flat-bed jelly duplicator - the sort which

produced a hazy purple image that looked as though it were fading before your

eyes. Is it still possible to purchase the fluid for these ancient contraptions?

Perhaps not, for the menu sheets had been pasted and repasted with hand-written

strips which seasonally adjusted the dishes on offer. We were back in the

post-war era of acute paper shortage.

some time in the distant past on a flat-bed jelly duplicator - the sort which

produced a hazy purple image that looked as though it were fading before your

eyes. Is it still possible to purchase the fluid for these ancient contraptions?

Perhaps not, for the menu sheets had been pasted and repasted with hand-written

strips which seasonally adjusted the dishes on offer. We were back in the

post-war era of acute paper shortage.

The offerings consisted entirely of classical French dishes

which might have been on the carte when the Gramonds opened in 1967. No tapenade

sushi here!

I settled on what seemed the inevitable choices: foie gras de canard des

landes maison (fresh duck liver from Gascony lightly coated with coarse

salt and flash-fried in butter) and, now that we were in the game season,

civet de lièvre à la Française (a rich and complicated

stew of wild hare cooked in several stages with wine, bacon and vegetables

and thickened at the last minute with the hare's blood). For desert I ordered

in advance the souflé [sic] au Grand Marnier.

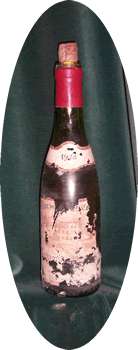

The wine  list was as historic as the rest of the establishment. There was

a long list of Bordeaux and Burgundies from the proprietors Ch. Chapelle et

Fils, an old firm with whom Mssr. Gramond had done business for many years.

Tucked

in among them was a 1974 Petrus at 8900ff. I had reached one of those rare

moments when I wished I were truly rich. These were wines not intended to

reach their prime for at least a generation - "time is money" was

then a vulgarism. From this venerable list Madame Gramond guided me to a half-bottle

of Chassagne Montrachet 1978, unusually a red rather than a white. With it

came a great wide glass which would have sufficed as a baptismal font. The

wine leapt out of the bottle with the freshness and agility of a long imprisoned

genie. I have the bottle before me, its label reducing rapidly to powder.

I take out the cork and catch a slight remaining whiff of its aristocratic

liveliness.

list was as historic as the rest of the establishment. There was

a long list of Bordeaux and Burgundies from the proprietors Ch. Chapelle et

Fils, an old firm with whom Mssr. Gramond had done business for many years.

Tucked

in among them was a 1974 Petrus at 8900ff. I had reached one of those rare

moments when I wished I were truly rich. These were wines not intended to

reach their prime for at least a generation - "time is money" was

then a vulgarism. From this venerable list Madame Gramond guided me to a half-bottle

of Chassagne Montrachet 1978, unusually a red rather than a white. With it

came a great wide glass which would have sufficed as a baptismal font. The

wine leapt out of the bottle with the freshness and agility of a long imprisoned

genie. I have the bottle before me, its label reducing rapidly to powder.

I take out the cork and catch a slight remaining whiff of its aristocratic

liveliness.

The foie gras was like several other perfect examples

I've had - a duck liver, like a steak, is hard to spoil if the raw ingredient

is of the highest quality and you don't overcook it.  But

the civet de lièvre was a revelation.I had eaten a similar recipe

two nights before at Le Petit Marguery, a grand institution with an army of

chefs. It was truly excellent; but this version, prepared by a single unassisted

chef in a tiny kitchen, made bells ring and whistles blow. Towards the end

of the evening another solitary diner arrived for a late meal and I was so

well lubricated as to tell him that the hare was magnifique. He thanked

me with evident sincerity on his way out.

But

the civet de lièvre was a revelation.I had eaten a similar recipe

two nights before at Le Petit Marguery, a grand institution with an army of

chefs. It was truly excellent; but this version, prepared by a single unassisted

chef in a tiny kitchen, made bells ring and whistles blow. Towards the end

of the evening another solitary diner arrived for a late meal and I was so

well lubricated as to tell him that the hare was magnifique. He thanked

me with evident sincerity on his way out.

I was still ensconced, working my way slowly through a soufflé so light that it threatened to lead me a merry chase around the dining room. (Earlier I had heard the ominous sound of an electric whisk, but the finished product showed no ill effects.) Meanwhile the music from the kitchen had changed to the love duet from Tristan und Isolde. I was well and truly infatuated.

Mssr. Gramond came out of the kitchen for a last goodbye. He told me proudly that he was a royalist. A royalist, in France, in 2001? It was no more incongruous than the ambience and the cuisine he was so staunchly defending. This is not a cheap establishment - my bill came to 767ff, about half of which was the memorable half-bottle. In Paris today, who is willing to pay that kind of money to eat in an ancient bistro which appears in none of the fashionable guides? François Mitterand and the various bishops, professors and academicians who used to lunch here are long departed. So what keeps it going? Perhaps a handful of devotees who are determined to preserve this precious remnant of a disappearing tradition.

Chez Gramond, 5, rue de Fleurus, 6th Arrond., Tel: 01.42.22.28.89

© 2001 John Whiting

![]()